With my childhood spent during WW2 and my adolescence during the Cold War of the 1950s, living with The Bomb when people took it seriously, I was programmed to expect that the end was, in fact, coming.

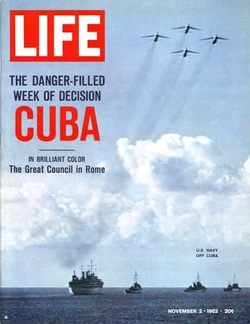

This feeling reached a climax during the Cuban Missile

Crisis of 1962.

I remember vividly that most dangerous October day, slight

crispness in the air, brilliant blue sky, the walk from my lower Sullivan Street apartment to the nearest local subway stop . . .

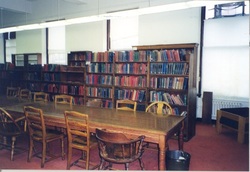

. . . to take the train up to Columbia University where I worked in the library of the School of Journalism. I still can remember a sudden euphoria, an acceptance of doom, a great lifting of weight from my heart. There was this moment. This instance. There was no more.

burst into tears and rush from the room. I wanted tosay,“It’s all right.” But there was no way to explain my own sense of joy.

Now this euphoria had a serious downside: for years to come I could only live in the present instant. There might not be another. There was no future, and there was no need to plan for one. Hedonism raised its pleasant head.

A year or so later I became interested in ballet, particularly

the New York City Ballet, when a co-worker invited me to accompany her to a performance of George Balanchine's “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” at City Center.

Now in my later years, and particularly this day and this week, I am starting to feel that old 1962 euphoria again. Where is my Balanchine?

(It may be Terrence Malick, but I’m not sure yet.)

But I guess the euphoria is preferable to fear and dread.

Isn’t it?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed