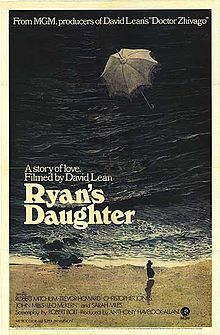

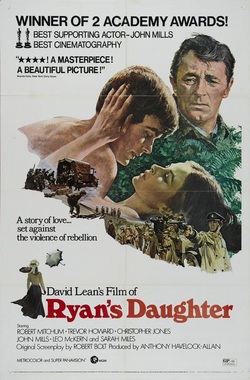

RYAN'S DAUGHTER, 1970

In the fall of 1970, MGM asked Tom to oversee publicity during the New York screenings, premiere, and release of David Lean’s Ryan’s Daughter. He worked hard, he did a good job, and he had a great time.

Those who showed up for the event included Lean, writer Robert Bolt, actors Robert Mitchum, Trevor Howard, and John Mills, cinematographer Freddie Young, and property master Eddie Fowlie. Sarah Miles (Mrs. Robert Bolt) and the other young star, Christopher Jones, did not make the trip.

Tom and Robert Mitchum bonded immediately

when Tom went to pick him up at the airport. Tom always had a great knack for

meeting people, and it worked exceedingly well in this instance. Tom always did his

homework well in advance, and I am certain that he had refreshed himself on

Mitchum’s career before meeting him. (As he says in his chapter about what a

publicist does in A Fever of the Mad,

‘”What have you done in the past, Mr. Mitchum?” is not a question you want to

ask.’) This encounter with Mitchum helped them form a relationship that would come in handy a couple of years later on The Wrath of God. Tales about Mitchum will be held for that section.

Trevor Howard was great guy but a

challenge. He drank a lot, and it was a job for Tom to keep up. He finally

realized that Howard wasn’t counting, and that made things easier. The day he

arrived, someone not thinking it through carefully had got tickets for him and

Tom to see Sondheim’s Company.

Perhaps not the best choice for a tired Brit just off the plane from England.

At intermission, realizing Howard’s tiredness and discomfort, Tom asked if he

wished to leave. Howard thought that a great idea, and they retired to the

nearest bar for some restorative.

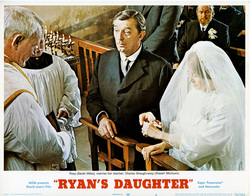

John Mills played Michael, and I guess we’d have to fall back on the old phrase village idiot to describe the role. Ugly teeth. Unable to speak. A gimpy leg. Perfect Academy Award bait, and he did in fact win an award for Best Supporting Oscar. Mills later got in touch with Tom and said that he believed that the publicity Tom got during these weeks in New York were directly responsible for his win. The only other win for the film was Freddie Young’s cinematography.

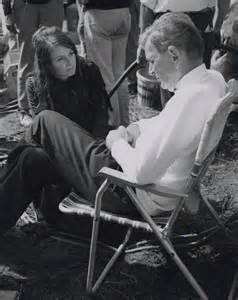

Tom got along well with David Lean and Robert Bolt. Bolt was still in New York when the first reviews came out. John Simon’s was particularly damning, and certainly he had a right to his opinion, but his negative comments about Sarah Miles, Mrs. Bolt, centered so much on her physical appearance and his dislike of it that Bolt was ready to take up pistols at dawn. Or at least resort to fisticuffs. Wiser heads prevailed.

There were rumors of problems

between Lean and Mitchum on location, but any such difficulties never surfaced

during their time jointly and separately with Tom in New York. Lean, like

Mitchum, was a most loquacious gentleman, and Tom loved hearing his tales from

this recent movie and earlier ones. Tom was particularly enthralled with one

long conversation with Lean and Eddie Fowlie in which they discussed at great

length the matter of keeping footprints out of the sand in Lawrence and out of the snow in Zhivago. Although Fowlie received

billing as “property master,” Tom gathered that his role on Lean’s later films

involved much more than that.

Lean early on told Tom that he

had hired Christopher Jones because of his performance in The Looking Glass War. What he had not known was that Jones’ voice

had been dubbed throughout by another actor. To Lean’s horror, Jones could not

do the proper accent, and his acting was, at best, weak. Lean and Bolt trimmed

his lines to a minimum and Lean used him more as a visual object than a

character. Luckily the role lent itself to that approach. Still, what lines

remained had to be dubbed. For me, one of Lean’s greatest successes on this

movie was his ability to work with weak material like Jones and make him more

than acceptable in the role.

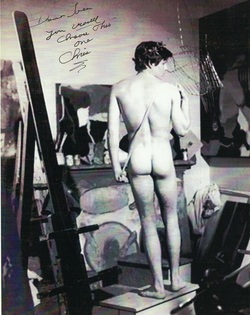

Tom had met Christopher Jones earlier when he was working as a staff publicist at American International Pictures during the time when Three in the Attic, featuring Jones, was released. He had liked Jones very much, although he did find him to be a bit lacking in intellectual vigor. (As Tom said to me, "He's sort of vague.") He asked Jones if he would autograph a still. When Jones agreed, Tom presented him with this one as a joke. He had another one in reserve, never expecting that Jones would sign this naked rear shot. But Tom had the good sense to ride with it when Jones grinned and signed.

The movie? Tom and I both enjoyed

it. Certainly it is pretty to look at. Certainly it looked and sounded great on that great

big screen at the Ziegfeld Theater in New York, where the fully-packed

screenings were held. Yes, I know that

one of the objections is that with such a little story, the big screen

overwhelms. Still, we thought grand helped.

The screenings weren’t successful.

With a great big New York invitational screening, if something about the film

comes across as a little bit too much, the audience can be damning. It happened

with this one, in the long poetic love scenes between Christopher Jones and

Sarah Miles in the “enchanted forest.”

Ripples of laughter started, and once that starts, it is hard for the

audience to get back into the mood of the film. Especially when New York

screening audience members are trying to show each other how above it all they

really are. (I saw it happen a few years later at the Ziegfeld with a screening of the first Rollerball. At least Ryan’s Daughter did not get the round of

boos that one got at the end.)

Lean did not make another movie until A Passage to India some 14 years later, his last movie. Too bad. I’d like to have seen what he would have done in between. He was an old-fashioned director, damning in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Definitely Ryan’s Daughter and Doctor Zhivago were old-fashioned movies, but still, ones that were using the new technologies in attractive and fairly interesting ways. Even Lawrence of Arabia has its old-fashioned touches, as new and fresh as it seemed when it first came out.

Speaking of Lawrence, Tom and I went to the special screening to introduce the restored print of that one back in the 1980s, again at the Ziegfeld. I think it speaks something about Lean to know that among the dignitaries lined up in front of the screen in tribute to him were both Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese.