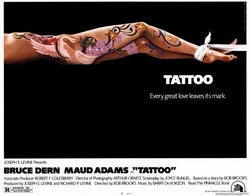

TATTOO, 1981

Well before Nebraska, Bruce Dern played Karl Kinsky in Tattoo. He was a seriously disturbed tattoo artist who was stalking a model played by the beautiful Maude Adams. For some reason Dern wasn't nominated for a Best Actor Academy Award. Anything else you need to know?

Let's let Tom tell it himself, from A Fever of the Mad:

Well before Nebraska, Bruce Dern played Karl Kinsky in Tattoo. He was a seriously disturbed tattoo artist who was stalking a model played by the beautiful Maude Adams. For some reason Dern wasn't nominated for a Best Actor Academy Award. Anything else you need to know?

Let's let Tom tell it himself, from A Fever of the Mad:

On Tattoo I had not only [Joseph E.] Levine to deal with toward the tail end of

his producing career but Bruce Dern as well. Dern had a wicked sense of humor

that I often enjoyed, particularly when I wasn’t its target. In the film Dern

played a characteristically psycho role with a degree of personality carry-over

from character to actor but insisted from day one that the character was not a

psycho: he kidnapped and tattooed girls not because he was crazy but because it

was his way of expressing love. Five years after the film’s release, Dern

admitted in print that the role was as over the edge as any he’d ever played,

and God and every movie-goer knows that Dern has played some lulus. But during

production, Dern was like Rodney Dangerfield demanding respect; he wanted

respect for his character, and this attitude didn’t make life any easier for me

or for the unit photographer, whom I supervised. Dern insisted that no

photographs be taken of him when he was engaged in a “menacing gesture.” After

I argued with him about the need for stills of a scene in which his character

sticks a hypodermic needle into the arm of co-star Maude Adams, he started

giving me a new (fortunately temporary) salutation when I appeared on set:

scumbag. Imagine a nice person like me in a screaming match with Bruce Dern as

you’ve seen him on screen at his most characteristically psycho! Indeed, what was I doing in a job like that? Later on

I shouted him down after he had blown up at me because I had shown some photos

of Bruce to his wife and to Maude Adams before he saw them. It’s not the way a

unit publicist likes to work, nor should he have to. Still, playing the heavy

opposite Bruce Dern was sort of fun as long as such scenes were minimal. Most

films are fun. At least in retrospect. While you’re working on them, the stress

is such that you hardly have time to notice.

And producer Joseph E. Levine?

You would think that a seasoned producer like Joseph E. Levine of Embassy Pictures would have a clearer idea than most of what a unit publicist does. Nevertheless, two days after the completion of principal photography on Tattoo, he sent me word that I was dismissed, my job done. I sent word right back: my job wasn’t done by half. If I left then, he would sacrifice all writing materials that would be needed at the time of the film’s release: final production notes, biographies of all the principals, synopsis, features on the art and history of tattooing, etc., copy that would normally be incorporated into press kits for distribution to the media at the time of the film’s release. His associates passed the word along to him (I tried to deal with him as indirectly as possible at all times). I could imagine him going into one of his famed tirades, screaming that I was cheating him, demanding to know why I hadn’t written the stuff earlier (quick answer: no time, too busy with all the other stuff that a unit publicist is involved with during shooting). He passed the word along to me, “You got one more week.”

I pulled the material together in less time than that, actually, and got it to Levine. I’d been told that he wanted to read every word. He did, that night. Next day I ran into him in the lobby of his office building, and he beamed at me. “I read what you wrote. I like it. I didn’t know you guys did that.”

Translated: “I didn’t know unit publicists wrote the kind of polished copy that appears in press kits.” The mind boggles. At the time of Tattoo, Levine was a veteran producer and distributor with more than twenty solid and successful years behind him. I had worked on his staff in 1967 at the time both The Graduate and The Producers were in production and had written and supervised hundreds of weekly mailings to exhibitors and press about both films. I wondered if Levine thought I’d made it all up out of my head without a bedrock of unit copy to guide me. Did he think the unit publicists acted merely as a guide or deterrent to visits from the press?

His reputation for firing unit publicists was notorious, and hilarious stories (well, hilarious to those who heard them later) were told in the industry about at least two such firings. I had been determined to make it through Tattoo and had concluded that staying out of his way was as good a way as any of assuring job longevity. It almost backfired on me. After successfully eluding Levine for two weeks, he paid a rare surprise visit accompanied by his chauffeur to the Tattoo production office. Eyeing me, he raised his walking stick like a wand and advanced on me like something wicked come this way from Oz, shouting, “I’ve caught you at last!” He struck me as funny, a demented Frank Morgan, but he seemed determined to strike me otherwise. “I’ve never struck anybody in twenty years,” he said, plainly demonstrating his intention of remedying that. I tried to laugh it off as the joke it clearly was not and got out of the office fast while everybody including the chauffeur looked on dumbstruck.

You would think that a seasoned producer like Joseph E. Levine of Embassy Pictures would have a clearer idea than most of what a unit publicist does. Nevertheless, two days after the completion of principal photography on Tattoo, he sent me word that I was dismissed, my job done. I sent word right back: my job wasn’t done by half. If I left then, he would sacrifice all writing materials that would be needed at the time of the film’s release: final production notes, biographies of all the principals, synopsis, features on the art and history of tattooing, etc., copy that would normally be incorporated into press kits for distribution to the media at the time of the film’s release. His associates passed the word along to him (I tried to deal with him as indirectly as possible at all times). I could imagine him going into one of his famed tirades, screaming that I was cheating him, demanding to know why I hadn’t written the stuff earlier (quick answer: no time, too busy with all the other stuff that a unit publicist is involved with during shooting). He passed the word along to me, “You got one more week.”

I pulled the material together in less time than that, actually, and got it to Levine. I’d been told that he wanted to read every word. He did, that night. Next day I ran into him in the lobby of his office building, and he beamed at me. “I read what you wrote. I like it. I didn’t know you guys did that.”

Translated: “I didn’t know unit publicists wrote the kind of polished copy that appears in press kits.” The mind boggles. At the time of Tattoo, Levine was a veteran producer and distributor with more than twenty solid and successful years behind him. I had worked on his staff in 1967 at the time both The Graduate and The Producers were in production and had written and supervised hundreds of weekly mailings to exhibitors and press about both films. I wondered if Levine thought I’d made it all up out of my head without a bedrock of unit copy to guide me. Did he think the unit publicists acted merely as a guide or deterrent to visits from the press?

His reputation for firing unit publicists was notorious, and hilarious stories (well, hilarious to those who heard them later) were told in the industry about at least two such firings. I had been determined to make it through Tattoo and had concluded that staying out of his way was as good a way as any of assuring job longevity. It almost backfired on me. After successfully eluding Levine for two weeks, he paid a rare surprise visit accompanied by his chauffeur to the Tattoo production office. Eyeing me, he raised his walking stick like a wand and advanced on me like something wicked come this way from Oz, shouting, “I’ve caught you at last!” He struck me as funny, a demented Frank Morgan, but he seemed determined to strike me otherwise. “I’ve never struck anybody in twenty years,” he said, plainly demonstrating his intention of remedying that. I tried to laugh it off as the joke it clearly was not and got out of the office fast while everybody including the chauffeur looked on dumbstruck.

Another story involving himself and Levine that Tom loved to tell:

Tom was working on the staff at Embassy Pictures when Mel Brooks's The Producers was being released. Tom had just sneaked off to an invitational screening of 2001 that afternoon (I was there too!), and when he got back to the office, Levine said "See this!" and sent him in to a screening of The Producers. (By the way, Tom loved both movies.) Levine hated The Producers but for some reason wanted Tom's opinion. Tom reported, "Mr. Levine, it's wonderful! It's going to become a cult classic and will run for years!" Levine put his head down on his arms, reared up, sighed, and said, "Tom, I hope you're right. I hope you're right." And Tom was.

But before we praise Tom's prescience too much, it's only fair to report that he left Embassy as soon as he saw a screening of The Graduate and he wanted to get out while the getting was good. He thought it was a terrible film that would probably bring down Embassy Pictures. He never changed his mind about the movie. To some extent I can understand his opinion. But he had so focused on what he found bad in the movie that he missed what was new and different.

Tom was working on the staff at Embassy Pictures when Mel Brooks's The Producers was being released. Tom had just sneaked off to an invitational screening of 2001 that afternoon (I was there too!), and when he got back to the office, Levine said "See this!" and sent him in to a screening of The Producers. (By the way, Tom loved both movies.) Levine hated The Producers but for some reason wanted Tom's opinion. Tom reported, "Mr. Levine, it's wonderful! It's going to become a cult classic and will run for years!" Levine put his head down on his arms, reared up, sighed, and said, "Tom, I hope you're right. I hope you're right." And Tom was.

But before we praise Tom's prescience too much, it's only fair to report that he left Embassy as soon as he saw a screening of The Graduate and he wanted to get out while the getting was good. He thought it was a terrible film that would probably bring down Embassy Pictures. He never changed his mind about the movie. To some extent I can understand his opinion. But he had so focused on what he found bad in the movie that he missed what was new and different.