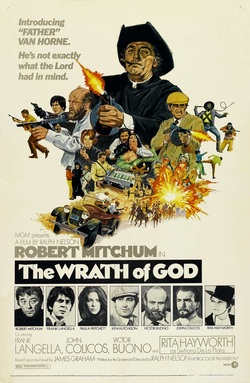

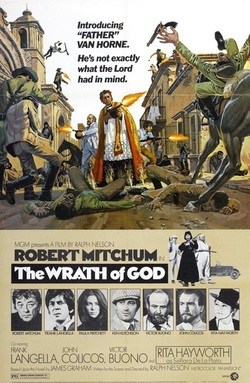

THE WRATH OF GOD, 1972

Tom should have written this one. In fact, he intended to do so. He made several starts, but when I was going through his writings after his death not a single one still existed. I’ve never been sure why. Too much material? Concern over which cats should be allowed out of which particular bags? Had there been material, it would have ended up in A Fever of the Mad. Since Tom did not get around to it, I’ll do what I can both from memories of his tales and from my own three-week visit with Tom in Mexico during production.

In November 1971 just before Thanksgiving Tom was called home to New Mexico: his stepmother Leanah’s cancer had progressed and it looked like the end was near. Lars McSorley at MGM had been dickering with Tom about his taking a staff position at MGM, which Tom was considering but was not sure that he wanted. Still, he had given Lars the Las Cruces phone number. Now, in Tom’s own words from his family memoir Baker’s Daughter, Miller’s Son:

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No, the call wasn’t about the staff job offer, Lars said, although the offer was still on the table should I want to reconsider. They were firing the publicist on The Wrath of God, filming on locations in Mexico. They wanted to replace this guy with me. I tried to beg off, using Leanah’s illness as my excuse. Which it was, but additionally I didn’t want to have to drive in Mexico. Lars must have read my mind. “You’ll have your own car and driver,” Lars said. The salary was terrific, the expenses allowed even better, “And you’ll have Rita Hayworth to run around with.” I hesitated. “You know your mother’s dying,” Lars told me. “It’s not like you can do a lot for her now. I know you want to be with her, but what more can you do, stay with her till the end? Give her support? From what you tell me she has ample support. Who knows when the end will be, Tom? We need you in Mexico.”

I would have to leave the Sunday after Thanksgiving, the 28th. Damn it, I didn’t want to go. Lars made it sound like an obligation. Also like if I didn’t take this job I wouldn’t be offered any more. I told him to let me know when and where. They would make the arrangements. I would be notified.

We got up at 4:30 Sunday morning. Norma woke me. I don’t know where Jane and Walter and the kids slept, but somehow we were all gotten up and gotten off. Norma was standing at the screen door, latching it as we drove off. She was crying. It was so sad to look back and see her crying, closing the door. How I wished this job I was going to hadn’t happened right then. Such execrable timing.

Tom should have written this one. In fact, he intended to do so. He made several starts, but when I was going through his writings after his death not a single one still existed. I’ve never been sure why. Too much material? Concern over which cats should be allowed out of which particular bags? Had there been material, it would have ended up in A Fever of the Mad. Since Tom did not get around to it, I’ll do what I can both from memories of his tales and from my own three-week visit with Tom in Mexico during production.

In November 1971 just before Thanksgiving Tom was called home to New Mexico: his stepmother Leanah’s cancer had progressed and it looked like the end was near. Lars McSorley at MGM had been dickering with Tom about his taking a staff position at MGM, which Tom was considering but was not sure that he wanted. Still, he had given Lars the Las Cruces phone number. Now, in Tom’s own words from his family memoir Baker’s Daughter, Miller’s Son:

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No, the call wasn’t about the staff job offer, Lars said, although the offer was still on the table should I want to reconsider. They were firing the publicist on The Wrath of God, filming on locations in Mexico. They wanted to replace this guy with me. I tried to beg off, using Leanah’s illness as my excuse. Which it was, but additionally I didn’t want to have to drive in Mexico. Lars must have read my mind. “You’ll have your own car and driver,” Lars said. The salary was terrific, the expenses allowed even better, “And you’ll have Rita Hayworth to run around with.” I hesitated. “You know your mother’s dying,” Lars told me. “It’s not like you can do a lot for her now. I know you want to be with her, but what more can you do, stay with her till the end? Give her support? From what you tell me she has ample support. Who knows when the end will be, Tom? We need you in Mexico.”

I would have to leave the Sunday after Thanksgiving, the 28th. Damn it, I didn’t want to go. Lars made it sound like an obligation. Also like if I didn’t take this job I wouldn’t be offered any more. I told him to let me know when and where. They would make the arrangements. I would be notified.

We got up at 4:30 Sunday morning. Norma woke me. I don’t know where Jane and Walter and the kids slept, but somehow we were all gotten up and gotten off. Norma was standing at the screen door, latching it as we drove off. She was crying. It was so sad to look back and see her crying, closing the door. How I wished this job I was going to hadn’t happened right then. Such execrable timing.

I was

met by an MGM representative and his wife in Mexico City. He drove me next day

to the film’s location, Hacienda Vista Hermosa at Tequesquetengo. Robert

Mitchum lit up when he saw me and I found myself having drinks with him in his

room in no time. It was like Ryan’s

Daughter all over again. (I had done release publicity on Ryan’s Daughter, on which I worked

closely with Robert Mitchum and the film’s director David Lean and writer

Robert Bolt.)

I spent one night at Hacienda Vista Hermosa, a grand sprawling seedy hotel of sorts, perfect for film noir which this movie wasn’t but should have been. The company moved next day to Guanajuato for filming in the nearby ghost town of La Luz, where the company had restored the town square and a hacienda facade. The Catholic Church on the square was still intact and perfect for a number of scenes, both interior and exterior. We were there a week when Leanah died.

Norma called me at my room in the Guanajuato Hotel on Tuesday morning to tell me that Leanah had died the previous night. I didn’t see how I could possibly get away. Though I had expected her death, news of it hit me hard. My driver, Delfino, took me to the La Luz location, where word of my mother’s death (I hadn’t qualified her as stepmother) had already circulated. The production manager, a very nice British guy (many of the crew were from England) came up to me to commiserate. I started to tell him about her illness, but couldn’t. I choked up, about to cry. He told me he’d already talked to Lars McSorley and the film’s associate producer. They were sending a replacement from Los Angeles for me for a week. I was to leave Mexico City that evening, then fly directly to Juarez that night. I was supposed to meet Rita Hayworth that afternoon, arriving in Mexico City from Los Angeles. Press and photographers had been alerted. “You can still do it,” the production manager said, adding, “if you’re up to it. If you’re not, I’ll send Maggie.” Maggie Netter was my assistant, the daughter of the second head of MGM, not much experience as a publicist, this being a token job for her with hardly anything for her to do, but I loved having her around to hang out with. “No, I’ll do it,” I said.

I spent one night at Hacienda Vista Hermosa, a grand sprawling seedy hotel of sorts, perfect for film noir which this movie wasn’t but should have been. The company moved next day to Guanajuato for filming in the nearby ghost town of La Luz, where the company had restored the town square and a hacienda facade. The Catholic Church on the square was still intact and perfect for a number of scenes, both interior and exterior. We were there a week when Leanah died.

Norma called me at my room in the Guanajuato Hotel on Tuesday morning to tell me that Leanah had died the previous night. I didn’t see how I could possibly get away. Though I had expected her death, news of it hit me hard. My driver, Delfino, took me to the La Luz location, where word of my mother’s death (I hadn’t qualified her as stepmother) had already circulated. The production manager, a very nice British guy (many of the crew were from England) came up to me to commiserate. I started to tell him about her illness, but couldn’t. I choked up, about to cry. He told me he’d already talked to Lars McSorley and the film’s associate producer. They were sending a replacement from Los Angeles for me for a week. I was to leave Mexico City that evening, then fly directly to Juarez that night. I was supposed to meet Rita Hayworth that afternoon, arriving in Mexico City from Los Angeles. Press and photographers had been alerted. “You can still do it,” the production manager said, adding, “if you’re up to it. If you’re not, I’ll send Maggie.” Maggie Netter was my assistant, the daughter of the second head of MGM, not much experience as a publicist, this being a token job for her with hardly anything for her to do, but I loved having her around to hang out with. “No, I’ll do it,” I said.

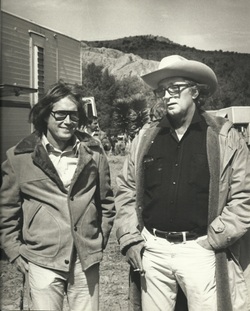

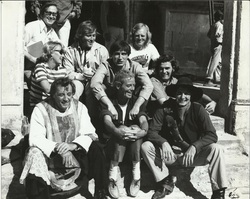

On location at La Luz, Mexico

Rita was something else. “I’ve been doing this all my life,” she told me, posing for swarms of photographers at the airport. She was in her early fifties, Alzheimer’s fast closing in on her (although neither she nor we knew that), and this would turn out to be her last movie (she simply couldn’t remember lines), but she still had glamour, presence, the name. It was synonymous with sex goddess. I had dinner with her in her hotel suite at the Camino Real that evening before catching my night flight for Juarez. [Note: Tom doesn’t say so here, but Miss Hayworth was deeply solicitous of Tom that evening and sympathetic for his loss.] When I arrived, I feared nobody was meeting me. Within a few minutes, however, Harry, Norma, Betty Jo, and Florence showed up. We stopped for lunch at Leo’s before going on to Cruces. The funeral was on December 9. There were no pallbearers, none being necessary, although Leanah had made out a list of preferred pallbearers. The music chosen featured two of Leanah’s favorites, “Abide with Me” and “Londonderry Air.” I left on Sunday December12 to return to Mexico and the movie on which I worked well into the next year, a project that surely deserves its own memoir or at least a bigger hunk than what I can write about it in a “family memoir.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Rita was something else. “I’ve been doing this all my life,” she told me, posing for swarms of photographers at the airport. She was in her early fifties, Alzheimer’s fast closing in on her (although neither she nor we knew that), and this would turn out to be her last movie (she simply couldn’t remember lines), but she still had glamour, presence, the name. It was synonymous with sex goddess. I had dinner with her in her hotel suite at the Camino Real that evening before catching my night flight for Juarez. [Note: Tom doesn’t say so here, but Miss Hayworth was deeply solicitous of Tom that evening and sympathetic for his loss.] When I arrived, I feared nobody was meeting me. Within a few minutes, however, Harry, Norma, Betty Jo, and Florence showed up. We stopped for lunch at Leo’s before going on to Cruces. The funeral was on December 9. There were no pallbearers, none being necessary, although Leanah had made out a list of preferred pallbearers. The music chosen featured two of Leanah’s favorites, “Abide with Me” and “Londonderry Air.” I left on Sunday December12 to return to Mexico and the movie on which I worked well into the next year, a project that surely deserves its own memoir or at least a bigger hunk than what I can write about it in a “family memoir.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Me

again. As you can see, Tom could not return to New York prior to the Mexico

adventure. It was left to me to pack up clothing, certain reference books, and

other necessaries and ship them down to the movie location. (As it turned out,

they got delayed at the baggage room at the Mexico City airport and Tom didn’t

get them until well into January, when I was visiting the set. He and I and

Someone with Authority went to the airport, and quickly the big suitcase was

located.)

Robert

Mitchum: Difficult. A mean streak that bordered on sadism. A sense of humor

that bordered on sadism. Mercurial. Tom loved him. In fact, Mitchum and Paul

Newman were, Tom told a party of friends in Tuscaloosa who had asked, his

favorites of all the movie folk he had worked with. (Newman some years later, in a

discussion with Tom about Mitchum, expressed amazement at how well Tom and

Mitchum had gotten along. “I’d have been scared of the man,” Newman said.)

From the family memoir: "When I worked with him as publicist on a movie in Mexico two gray-haired American tourists got into the elevator with Mitchum in the Guanajuato hotel where we were staying. One of the women asked Mitchum deferentially for an autograph. Faking hard of hearing he said, “Suck what?” The man was outrageous, and he was continually breaking me up. Which he loved. I heard him use the line a couple of other times, once to me when I tried to confer with him on location and was whispering in his ear. “Suck what?” he shot over his shoulder. I thought Rita Hayworth, sitting beside him, was going to choke. I thought I was. Not myself so much as him. But I laughed appropriately and let it pass. With Mitchum that was the best way unless you really wanted to get verbally clobbered. To have known and worked with him (on two occasions) was a real treat though."

Mitchum seemed to have blow-job on the brain. When Tom was working with him in New York during the Ryan’s Daughter release, this exchange (here quoted from A Fever of the Mad) took place: Robert Mitchum told me in his laconic way of one film where the production manager told him they were going to have to get rid of the publicist. “Why?” Mitchum asked. “I like him.” “Because," said the production manager, “he’s a cocksucker.” “In that case,” said Mitchum, “you better get rid of the director as well.” Mitchum smirked. “Besides, isn’t that the first requirement for being a publicist?" When I didn’t respond, he said, “I hope you know I’m kidding." As laconic as he, I replied, “I hope you know I hoped so.”

I wonder if that movie might have been Night of the Hunter. Mitchum also told Tom that when Charles Laughton was casting him as the Preacher, he sat Mitchum down and said,” Bob, I feel obligated to tell you that I am a homosexual. Will that be a problem for you?” Mitchum looked at Laughton a few moments and said, “No shit!”

Probably Tom’s most difficult moment with Mitchum came after Mitchum had brought homemade brownies to the set. A published report indicated that the brownies had been, well, specially flavored. Initially Mitchum thought Tom responsible, and Tom was vehement in his own defense. Mitchum stormed off. In a couple of days he had quieted down. He told Tom, “I know who did it, and I know it wasn’t you.”

One of Mitchum’s biggest blow-ups was at a silver mine location where he, as a faux priest, was expected to bless the mine. Lots of extras, lots of set-up, lots of time taken with Mitchum just standing around waiting. He got tired of it, and unfortunately associate producer William S. Gilmore happened to land in his line of vision. Mitchum cut loose with a lengthy harangue accusing Gilmore of every sin known to man or beast, including certain actions that would have been difficult to perform with or without help. It went on and on at top volume. Gilmore stood there patiently and quietly left the set when Mitchum finally wound down. Obviously he, like Tom, had figured out that the best way to cope with Mitchum was to say out of the fight.

Mitchum was not at all averse to making comments, rarely positive, about certain women actors he had worked with. Personal habits and general cleanliness and sexual neediness tended to topics of his major disdain. I could mention names but I won’t.

Mitchum had lots of stories, and I wish that Tom had written them down. Of course, Tom did take them with more than a grain of salt. In the Note to the Reader before his novel The Curse of Vilma Valentine, Tom writes: The Curse of Vilma Valentine is a work of fiction. Actual persons are used to comment on Vilma and her times. With one exception, they are used fictionally, and the actions and words attributed to them are the fabrications of the author. The one exception is Robert Mitchum. His story of being hijacked on a Mexico road by a drunken gang waving machetes was told to the author by Mitchum himself on a movie location in Mexico. Anyone who knew Robert Mitchum may well understand that this story too may be fiction, or at least an embroidery on the facts.

From the family memoir: "When I worked with him as publicist on a movie in Mexico two gray-haired American tourists got into the elevator with Mitchum in the Guanajuato hotel where we were staying. One of the women asked Mitchum deferentially for an autograph. Faking hard of hearing he said, “Suck what?” The man was outrageous, and he was continually breaking me up. Which he loved. I heard him use the line a couple of other times, once to me when I tried to confer with him on location and was whispering in his ear. “Suck what?” he shot over his shoulder. I thought Rita Hayworth, sitting beside him, was going to choke. I thought I was. Not myself so much as him. But I laughed appropriately and let it pass. With Mitchum that was the best way unless you really wanted to get verbally clobbered. To have known and worked with him (on two occasions) was a real treat though."

Mitchum seemed to have blow-job on the brain. When Tom was working with him in New York during the Ryan’s Daughter release, this exchange (here quoted from A Fever of the Mad) took place: Robert Mitchum told me in his laconic way of one film where the production manager told him they were going to have to get rid of the publicist. “Why?” Mitchum asked. “I like him.” “Because," said the production manager, “he’s a cocksucker.” “In that case,” said Mitchum, “you better get rid of the director as well.” Mitchum smirked. “Besides, isn’t that the first requirement for being a publicist?" When I didn’t respond, he said, “I hope you know I’m kidding." As laconic as he, I replied, “I hope you know I hoped so.”

I wonder if that movie might have been Night of the Hunter. Mitchum also told Tom that when Charles Laughton was casting him as the Preacher, he sat Mitchum down and said,” Bob, I feel obligated to tell you that I am a homosexual. Will that be a problem for you?” Mitchum looked at Laughton a few moments and said, “No shit!”

Probably Tom’s most difficult moment with Mitchum came after Mitchum had brought homemade brownies to the set. A published report indicated that the brownies had been, well, specially flavored. Initially Mitchum thought Tom responsible, and Tom was vehement in his own defense. Mitchum stormed off. In a couple of days he had quieted down. He told Tom, “I know who did it, and I know it wasn’t you.”

One of Mitchum’s biggest blow-ups was at a silver mine location where he, as a faux priest, was expected to bless the mine. Lots of extras, lots of set-up, lots of time taken with Mitchum just standing around waiting. He got tired of it, and unfortunately associate producer William S. Gilmore happened to land in his line of vision. Mitchum cut loose with a lengthy harangue accusing Gilmore of every sin known to man or beast, including certain actions that would have been difficult to perform with or without help. It went on and on at top volume. Gilmore stood there patiently and quietly left the set when Mitchum finally wound down. Obviously he, like Tom, had figured out that the best way to cope with Mitchum was to say out of the fight.

Mitchum was not at all averse to making comments, rarely positive, about certain women actors he had worked with. Personal habits and general cleanliness and sexual neediness tended to topics of his major disdain. I could mention names but I won’t.

Mitchum had lots of stories, and I wish that Tom had written them down. Of course, Tom did take them with more than a grain of salt. In the Note to the Reader before his novel The Curse of Vilma Valentine, Tom writes: The Curse of Vilma Valentine is a work of fiction. Actual persons are used to comment on Vilma and her times. With one exception, they are used fictionally, and the actions and words attributed to them are the fabrications of the author. The one exception is Robert Mitchum. His story of being hijacked on a Mexico road by a drunken gang waving machetes was told to the author by Mitchum himself on a movie location in Mexico. Anyone who knew Robert Mitchum may well understand that this story too may be fiction, or at least an embroidery on the facts.

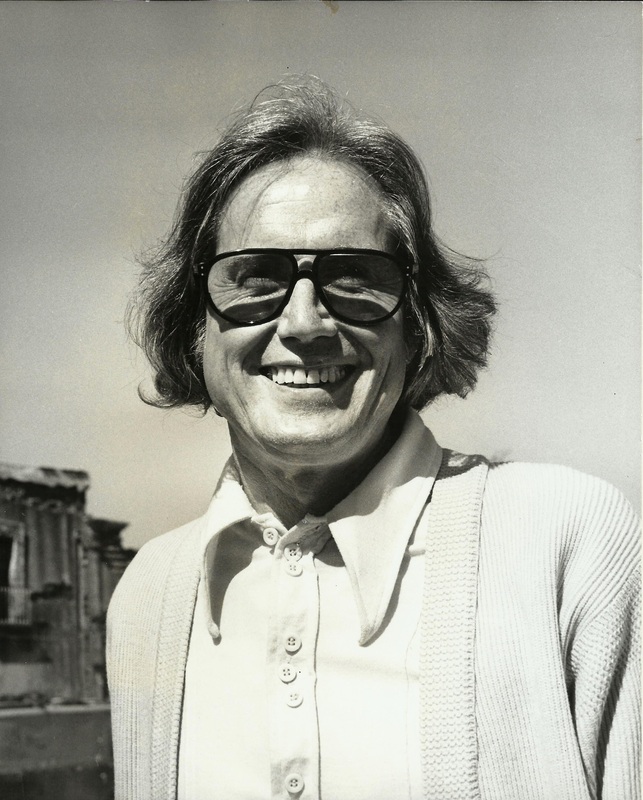

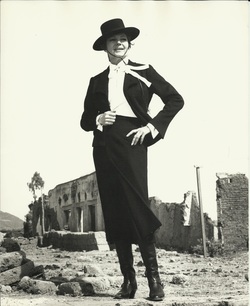

Rita Hayworth. The lady still looked good, if

perhaps not as youthful as once upon a time. Here she is in what may have been one of the very last posed glamor stills ever taken of her. In fact, Tom posed all of the central actors in the film at this location for a great series of stills (I no longer have them: consult the "Tom Miller Papers" at the Margaret Herrick Library).

The Wrath of God was the last movie she completed. She was signed for one more, but she had to withdraw from that one. On The Wrath of God she simply could not remember her lines, and they had to be filmed one line at a time. There were simple scenes that should have been filmed in the Guanajuato area for which they had to construct special sets later in Mexico City to be able to capture. When one watches the movie today, this difficulty is sadly apparent.

My first morning after I arrived in Guanajuato Tom and I had breakfast with Miss Hayworth. She was charming and friendly. On a couple of occasions we had dinner with her, after one of which we joined her in her room at the hotel for a nightcap. It is generally known that the lady drank. Vodka, or at least that night. Vodka and tonic. That’s what she started with. Then she would add more vodka (never more tonic) to top it off. Again and again. Years later Tom ventured the thought that perhaps she was drinking in order to give herself a reason for her not being able to remember.

Still, that evening she had a sharp mind about her past. She had pointed memories about Orson Welles and about her refusal to take money from any of the husbands she had divorced. (More than one of them seemed to have had no problem in taking money from her, however.) Somewhere along the way I made a remark beginning, “Rita, in the Hollywood of your day . . .” and she immediately interrupted that one: “My day is now!” she insisted. (Normally I’m smarter than that. Maybe I’d had the wee drop too much myself.) Good soul that she was, she immediately forgave me.

From time to time Tom’s driver, Delfino, had to drive Rita to the movie location. He grew to hate that. She was fearful of speed and insisted that he drive no more than 20 miles per hour.

Once in Mexico City Tom and Rita had dinner together. Afterwards, strolling through the hotel, they became aware of big doings in a large ballroom. Rita became curious and asked someone at the door. It was the Mexican equivalent of the Academy Awards. “Oh Tom, let’s go in!” Tom said, “But Rita, we are not invited!” Rita was having none of that. She pulled herself up and said, “But Tom. I am Rita Hayworth!” “So you are,” Tom said, and spoke with the man at the door. He sent an urgent message to the stage, and an excited announcement was made of her being in the room. Tom escorted her down front and assisted her up onto the stage, where she was greeted with an enormous ovation. They knew she was Rita Hayworth too

The Wrath of God was the last movie she completed. She was signed for one more, but she had to withdraw from that one. On The Wrath of God she simply could not remember her lines, and they had to be filmed one line at a time. There were simple scenes that should have been filmed in the Guanajuato area for which they had to construct special sets later in Mexico City to be able to capture. When one watches the movie today, this difficulty is sadly apparent.

My first morning after I arrived in Guanajuato Tom and I had breakfast with Miss Hayworth. She was charming and friendly. On a couple of occasions we had dinner with her, after one of which we joined her in her room at the hotel for a nightcap. It is generally known that the lady drank. Vodka, or at least that night. Vodka and tonic. That’s what she started with. Then she would add more vodka (never more tonic) to top it off. Again and again. Years later Tom ventured the thought that perhaps she was drinking in order to give herself a reason for her not being able to remember.

Still, that evening she had a sharp mind about her past. She had pointed memories about Orson Welles and about her refusal to take money from any of the husbands she had divorced. (More than one of them seemed to have had no problem in taking money from her, however.) Somewhere along the way I made a remark beginning, “Rita, in the Hollywood of your day . . .” and she immediately interrupted that one: “My day is now!” she insisted. (Normally I’m smarter than that. Maybe I’d had the wee drop too much myself.) Good soul that she was, she immediately forgave me.

From time to time Tom’s driver, Delfino, had to drive Rita to the movie location. He grew to hate that. She was fearful of speed and insisted that he drive no more than 20 miles per hour.

Once in Mexico City Tom and Rita had dinner together. Afterwards, strolling through the hotel, they became aware of big doings in a large ballroom. Rita became curious and asked someone at the door. It was the Mexican equivalent of the Academy Awards. “Oh Tom, let’s go in!” Tom said, “But Rita, we are not invited!” Rita was having none of that. She pulled herself up and said, “But Tom. I am Rita Hayworth!” “So you are,” Tom said, and spoke with the man at the door. He sent an urgent message to the stage, and an excited announcement was made of her being in the room. Tom escorted her down front and assisted her up onto the stage, where she was greeted with an enormous ovation. They knew she was Rita Hayworth too

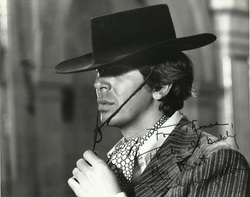

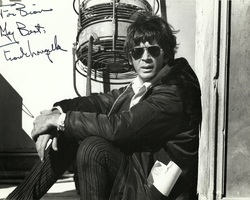

Frank

Langella played Rita Hayworth’s bad-boy son. Only a year or so before he had

had enormous success in Diary of a Mad

Housewife. He was young (maybe 33) and good-looking. No wonder that Miss

Hayworth let him into her bed, as he has himself so (in)famously announced in

his recent memoir. (Of course, that notoriously unreliable Mitchum did comment

to Tom in another context, “Frank is into older women.” If that were the case,

then lucky older women!) Tom found him pleasant, easy to get along with, and

professional.

If Tom knew about Langella and Hayworth, he never said anything to me (and I believe he would have). He did believe that Hayworth was eager for a man. She was lonely, she was not as young as she used to be, and she seemed to be seeking reassurance from the men around her.

[Note: Since writing the above, I have finally gotten around to reading Langella's memoir, Dropped Names. A review I had read made me thing it was simply a naming-names tell-all (and that can be fun too). But to my great pleasure, what comes across is not the sex that Langella has with some ladies of quite some fame but instead his great interest in, consideration for, and sympathy for the women. His account of his time with Rita Hayworth is most touching, and it dovetails nicely with Tom's assessment of her.]

If Tom knew about Langella and Hayworth, he never said anything to me (and I believe he would have). He did believe that Hayworth was eager for a man. She was lonely, she was not as young as she used to be, and she seemed to be seeking reassurance from the men around her.

[Note: Since writing the above, I have finally gotten around to reading Langella's memoir, Dropped Names. A review I had read made me thing it was simply a naming-names tell-all (and that can be fun too). But to my great pleasure, what comes across is not the sex that Langella has with some ladies of quite some fame but instead his great interest in, consideration for, and sympathy for the women. His account of his time with Rita Hayworth is most touching, and it dovetails nicely with Tom's assessment of her.]

Mitchum

liked Langella but had reservations about his performance. He told Tom that he thought

Langella was too over the top and too eye-popping, as if he were

in a silent movie. Tom didn’t argue (he didn’t with Mitchum), but he wasn’t

sure that Langella could have done much else with the role. It called for that.

In any case, Tom was most pleased with his experience working with Langella. He followed the actor's subsequent career with interest.

In any case, Tom was most pleased with his experience working with Langella. He followed the actor's subsequent career with interest.

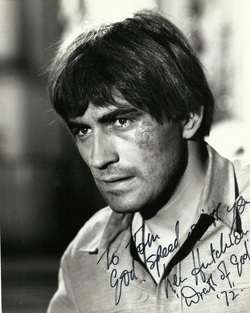

Ken

Hutchison played Emmett Keogh, the innocent who gets involved in Mitchum’s

faux-priest gun-running schemes. It is a role as large as Mitchum’s, and he is

quite wonderful in it. Tom thought this young actor born in Scotland some 28

years earlier was on the brink of a major career. Not to be. The IMDB bio

speculates that The Wrath of God “was

his one and only shot at the big time. Quite what went wrong is open to debate.

Some say he was wary of success and got cold feet. Whether that is true or not,

what certainly didn't help was his unruly behaviour which made studio execs nervous

of casting him again. He returned to Britain and continued his career as an

anonymous but astounding character actor.” According to Tom, wariness and cold

feet had nothing to do with it, but the unruly behavior did. Although he was

professional on set, his off-set behavior was extreme. He drank hugely. Mitchum

commented to Tom, “He’s patterning himself after actors like Burton and O’Toole

and the other big Brit drunks, but he needs to get the acting pattern down

before he starts on the drinking pattern.” This activity cumulated in a drunken

evening in which he fell on a glass coffee table and cut himself badly. The production

had to be shut down for 4 weeks: all the remaining scenes required his

participation, and too much had been shot in too many locations to reshoot with

another actor. Tom understood that insurance guys who turned up considered the

option of simply closing down the movie, but it was allowed to continue after

the hiatus.

Tom

liked Hutchison hugely, and the affection seemed to be returned. Ken was an

effusive young man, much given to hugs and embraces. At some point after the

accident that delayed production, Tom got the feeling that some folks on the

movie thought that Tom and Ken had been having an affair that that was a factor

in the drinking and the accident. That was not the case. And certainly Tom was

not there when the accident occurred.

I myself joined in Tom's dismay that Hutchinson's career did not take off. He makes a good impression in the movie in a performance filled with wit and charm.

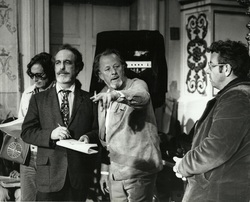

Here he is shown with fellow actors Mitchum and Victor Buono.

I myself joined in Tom's dismay that Hutchinson's career did not take off. He makes a good impression in the movie in a performance filled with wit and charm.

Here he is shown with fellow actors Mitchum and Victor Buono.

Not that

Tom was averse to playing around when out of town on a film, but he had a rule

of thumb not to get involved with the actors and other principal talents

involved. That, he felt, led to all sorts of unnecessary confusions. He did

have one ongoing fling with one person of some importance on this film,

instigated by that person, but it was a simple convenience and outlet for both

of them, not a grand passion, and it was conducted with discretion.

After all, a movie on location is much like a small town.

My presence seemed not to create any particular interest one way or another during the 10 days I spent with the company in Guanajuato before the move to Mexico City and my 10 days there. We’d party with actors and crew, and they all seemed to like me. I arrived in Guanajuato having just seen the first New York invitational screening of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, and I was much in demand among the British crew, several of whom had worked on the film and who were intensely curious about the end product of their combined work. Being able to report on the film (with a rave, incidentally) gave me a bit more credence with the crew than I might have otherwise had. The movie location was filled with fascinating people, major and minor actors and major and minor technicians, and all that I met were interesting. People working hard, serious about what they were doing. And there were lots of Brits on the movie: see the photo below along with the text of Tom's accompanying release:

My presence seemed not to create any particular interest one way or another during the 10 days I spent with the company in Guanajuato before the move to Mexico City and my 10 days there. We’d party with actors and crew, and they all seemed to like me. I arrived in Guanajuato having just seen the first New York invitational screening of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, and I was much in demand among the British crew, several of whom had worked on the film and who were intensely curious about the end product of their combined work. Being able to report on the film (with a rave, incidentally) gave me a bit more credence with the crew than I might have otherwise had. The movie location was filled with fascinating people, major and minor actors and major and minor technicians, and all that I met were interesting. People working hard, serious about what they were doing. And there were lots of Brits on the movie: see the photo below along with the text of Tom's accompanying release:

BRITISH BANDIDOS

On the old cathedral steps of the near-dormant mining village of la Luz, Mexico, the British contingent of MGM’s “The Wrath of God,” shooting here, gathered one day for a group shot; and everybody else wanted to get into the act, too, including non-Britisher and star Robert Mitchum (front, left) born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, who plays a renegade priest who says benediction with a machine gun.

The Britishers in the photo are Mitchum’s co-star Ken Hutchinson, center, and the two gentlemen to his rear on either side, Peter Sutton (sound mixer) on his right, and Robert Watts (production manager) on his left. Sitting beside him to his immediate left is Joe Dunton, video supervisor. Irish vocal coach for Hutchison, Don Geraghty, sits in front of Hutchison.

Producer-director Ralph Nelson became acquainted with these film people from the British Isles while filming “The Flight of the Doves” in Ireland, his film just prior to “The Wrath of God.”

Others in the photo are, at top left, unit publicist Tom Miller, and just below him, hair stylist Lynn Del Kail. The stunt man in the lower right hand corner is Benny Dobbins, who is here dressed as a 1920’s Latin American bandido. Like Mitchum, these three are North American gringos.

Also starring in the film are Rita Hayworth, who was born in New York City of Irish and Spanish parentage, and Frank Langella, who was born in Bayonne, New Jersey, of Italian parentage.

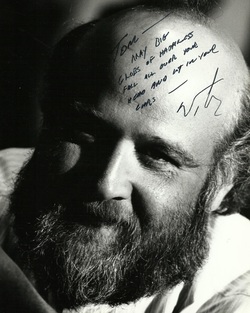

Victor Buono had what was basically the Sidney Greenstreet role (and if you don’t know what that means I’m surprised you got this far). Tom liked him hugely. Well-educated, witty, and charming. Always a pleasure to be around. I thought so too.

I was delighted when I saw where Buono autographed a picture for Tom. Maybe it is because I am bald as well and have been so for well more than 50 years.

Another actor who became a friend during the shoot was Gregory Serra, heavily bearded for his role in this one. He played a Really Bad Guy, so different from his real life persona.

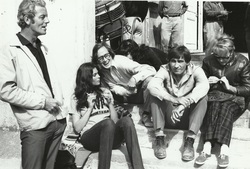

Here he is dining with Tom and Mr. and Mrs. Ken Hutchison.

Tom

adored Paula Pritchett. Who wouldn’t! She played Chela, the Mexican maiden who

cannot speak but makes beautiful music with Ken Hutchison. And then (spoiler here!) she shrieks out a warning at just the right moment and saves her lover's life. I fear this was her

last movie role. Maybe if it had done better . . .

Here she is with Tom, Ken, and Ken’s Irish vocal coach, Don Geraghty.

Here she is with Tom, Ken, and Ken’s Irish vocal coach, Don Geraghty.

Tom

seemed always to get along well with cinematographers, and Alex Phillips, Jr.

was no exception. While I was there, Phillips got married to a beautiful woman

who had a small role in the movie, and Tom and I both attended the reception.

My favorite and most memorable conversation with Phillips included his comment, “I’ve got nothing against queers! I used to fuck queers all the time when I lived in Greenwich Village!” And I suspect he was merely being truthful. He struck me as being like the old mule who when it started to itch would rub against the first post it came to along the road.

The photo doesn’t due him justice. It was remarkable how that blond hair and the tanned skin worked together. He was made for color! He had a long career as cinematographer in the United States and in Mexico.

My favorite and most memorable conversation with Phillips included his comment, “I’ve got nothing against queers! I used to fuck queers all the time when I lived in Greenwich Village!” And I suspect he was merely being truthful. He struck me as being like the old mule who when it started to itch would rub against the first post it came to along the road.

The photo doesn’t due him justice. It was remarkable how that blond hair and the tanned skin worked together. He was made for color! He had a long career as cinematographer in the United States and in Mexico.

Tom got along well with director Ralph Nelson, but it always remained just a working relationship. But then, directors are the busy guys on films and don’t have the downtime that actors do. Nelson’s work on this movie is certainly competent. Earlier films of his like Requiem for a Heavyweight, Lilies of the Field, and Charlie just possibly suffered a bit from overpraise, and it looked like the world wanted to cut him down to size with their reaction to this one. But who ever said that life was fair!

Mitchum seemed to like him, and Tom never heard him say anything bad about his director. And if Mitchum wanted to, he would have!

Tom was upset when he found out that he would be assigned MGM executive Doug Netter’s daughter Maggie as an assistant. He didn’t need an assistant! She’d just be in the way! To his delight, he found her a joy. And she actually did do a good job of helping Tom. Here Tom is with Maggie Netter and Frank Ramirez, an actor on the movie with whom Maggie formed a relationship that I believe continued after filming was over. Ramirez has had a successful career in film and television. I liked Maggie and Frank enormously. They were both extremely pleasant to me.

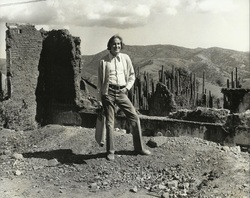

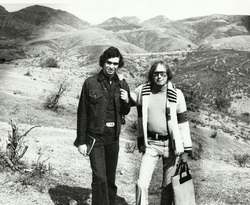

When the company was based in Guanajuato, most of the filming took place in the old silver-mining town La Luz, up in the hills and some distance away. The village square and the old church both featured prominently in the film. The area was lonely, desolate, and lovely. Or at least Tom and I both thought it lovely. Here’s a shot of Tom and some of the surrounding landscape:

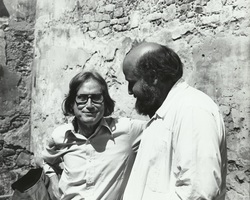

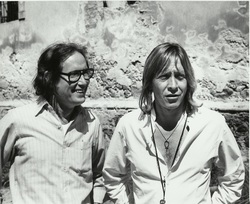

And here he is in the La Luz area with visiting reporter Steve Ditlea. His visit overlapped with mine. Nice guy. Ditlea was particularly enamored by meeting Rita Hayworth. He had adored her in Gilda. In fact, after we all got back to New York, the three of us got together to watch Gilda again.

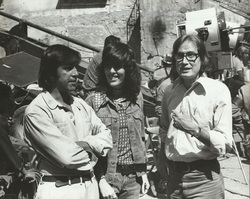

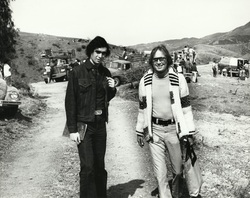

And this one is kind of fun because it shows some of the equipment in the background. Looks to me like they are packing it in after a hard day's work.

The movie itself? Well, it was released without critics' screenings on a double bill on 42nd Street. In those days that was a Bad Thing. The movie, while not a great undiscovered work of art, is not terrible, more than decently entertaining, and from today’s vantage point should be of interest because of the intersection of various talents involved in its making. Tom believed, and I think he had some justification in doing so, that during the pre-release time MGM was going through major changes in personnel at upper echelons, and just possibly this movie was thrown away because it was the product of “those earlier guys.” Even the poster art suggests lack of care.

I would like to see a restored print one of these days and distribution on Blu-ray. I’ll get it for my collection, and I’ll regret that Tom is not still around to participate in the commentary.