THE HAPPY HOOKER, 1975

Not a great success, but not the stinker that the previous year's Three Tough Guys had been (in spite of its Chicago location and stars Isaac Hayes, Fred Williamson, and Lino Ventura and the Isaac Hayes score). The Happy Hooker was the brainchild of Lynn Redgrave's then husband and agent/manager, John Clark. It was based on a memoir by Xaviera Hollander, a professional lady who just may be more interesting than the movie makes her: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xaviera_Hollander

This may be a good time to make

a comment or so about Tom’s own professionalism. He always started work on a

movie well before his paycheck started. He had a wealth of reference books

about movies and actors. In addition, he would spend hours at various

libraries, mostly at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at

Lincoln Center. He believed that anything he knew (or had recently refreshed

himself on) would serve him in good stead once he got to the set. As he says in

his chapter in A Fever of the Mad

about the duties of a unit publicist, “Publicist,

beware of not doing your homework ahead of time. ‘What have you done in the

past, Mr. Mitchum?’ is not a question you want to ask.”

A good (and amusing) example from The Happy Hooker: French actor Jean-Pierre Aumont was brought to New York to play one the Hooker’s clients. He and Tom got along like gangbusters, in part because Tom had done his homework and refreshed himself on every aspect of Aumont's career before he ever met him.

During an interview in which Aumont was asked a number of questions about his career, he would often look to Tom for facts and chronology. ("Yes, Jean-Pierre, that was in 1971 right after you had done . . .") Toward the close of the interview, the reporter, who no doubt considered himself liberated, asked, "How long have you two been together?" Tom and Aumont looked at each other and burst out laughing.

Tom and Aumont always got along wonderfully

With

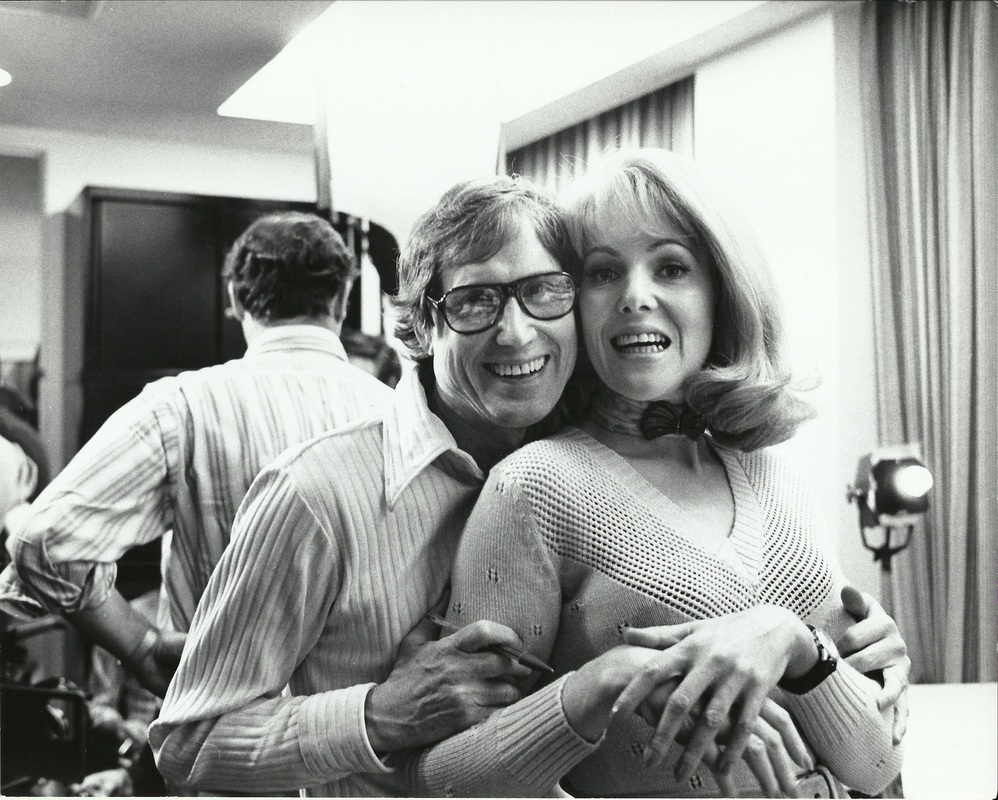

Lynn Redgrave it was a different story. Tom considered Ms. Redgrave to be

totally a professional. Not cuddly, in spite of some of the photographs with

Tom. But Tom respected professionalism.

As her husband, agent, and manager at the time, John Clark had a tendency to

inject himself in every aspect of the movie that involved his wife. Including,

of course, publicity. Tom quickly learned that Redgrave would side with her

husband in any matter in which there was a difference of opinion. He coped. His

modus operandi: try to persuade with calm reason, give in gracefully when

necessary, and always cover your ass with a memorandum.

Clark wanted a lot of publicity: interviews, column items, pictures in the media, etc. When the movie did not do great business on its release, Clark sued Cannon Films for not doing enough to publicize the film. The company lawyers got a copy of Tom's press book and presented it to the judge, who glanced through it and threw out the case. Subsequently Tom received a most complimentary letter from the producers.

Tom became good friends with co-writer William Richert, who later received some note for writing and directing cult favorites Winter Kills (1979) and American Success Story (1980). All told, he considered The Happy Hooker a pleasurable experience. More importantly, his first onscreen credit:

From A Fever of the Mad:

I received my first screen credit in 1974 with The Happy Hooker for Cannon Films, having already worked without film credit on four films for MGM (Alex in Wonderland, Shaft, The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, and The Wrath of God), two for Twentieth Century-Fox (The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds and The Last American Hero), and one for Paramount (Mikey and Nicky, filmed in 1973 but not released until 1976). The Publicists Guild made no issue over screen credit, and the individual publicist had to use such leverage as he or she could. I had asked for this credit on The Last American Hero, and executive producer Joe Wizan told me that I would get it but couldn’t deliver on his promise. Studio brass vetoed it, saying that it was not studio policy, the job being seen traditionally as (and in fact was) an extension of the studio’s publicity department.

Clark wanted a lot of publicity: interviews, column items, pictures in the media, etc. When the movie did not do great business on its release, Clark sued Cannon Films for not doing enough to publicize the film. The company lawyers got a copy of Tom's press book and presented it to the judge, who glanced through it and threw out the case. Subsequently Tom received a most complimentary letter from the producers.

Tom became good friends with co-writer William Richert, who later received some note for writing and directing cult favorites Winter Kills (1979) and American Success Story (1980). All told, he considered The Happy Hooker a pleasurable experience. More importantly, his first onscreen credit:

From A Fever of the Mad:

I received my first screen credit in 1974 with The Happy Hooker for Cannon Films, having already worked without film credit on four films for MGM (Alex in Wonderland, Shaft, The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, and The Wrath of God), two for Twentieth Century-Fox (The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds and The Last American Hero), and one for Paramount (Mikey and Nicky, filmed in 1973 but not released until 1976). The Publicists Guild made no issue over screen credit, and the individual publicist had to use such leverage as he or she could. I had asked for this credit on The Last American Hero, and executive producer Joe Wizan told me that I would get it but couldn’t deliver on his promise. Studio brass vetoed it, saying that it was not studio policy, the job being seen traditionally as (and in fact was) an extension of the studio’s publicity department.