| December 1, 2020. Today I start my retrospective of all Terrence Malic movies in the order of their release. Of course I have already seen all of them in that order, rushing out to the theater or grabbing the first DVD release in later years. Most I have seen at least twice, several many more times than that. But this will be my first attempt to watch them all consecutively in a short timeframe. I hope to average about one a week. |

This is a love letter, not a critique, and for that I make no apology. I’m writing it for myself, but I’m inviting you to step in and share if that is your desire. An offering, not a demand.

We begin at the beginning:

| BADLANDS (1973). Viewed December 1, 2020. A remarkable debut. Of course Malick’s job is made easier by two great young actors, Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, and a seasoned pro, Warren Oates. Kit Carruthers: Martin Sheen gives charm and humor and odd likeability to a man who is basically a cold serial killer. One forgets how beautiful young Sheen was at the time, and Malick uses that beauty without glamorizing him or the character. We know little of Kit’s backstory when he meets Holly. The look of the town and the time in which it is set makes me think of “The Tree of Life.” Could Kit be an alternate version of Jack, the oldest son and central character, if Jack lacked the family structure(s) provided by his parents? Yes, Jack comes from a conflicted family (nature and |

Kit would have been a sensation on social media today.

Voiceover: Malick’s first movie and his first use of voiceover. Already he is a master. Here the voice is only that of Holly, from the diary she keeps. It is a wonderful construct influenced by the kind of romance fiction a 15-year-old girl might have read at the time, aiming for poetry and charmingly failing. (The greater poetry is in the plain spoken dialogue.) It serves as counterpoint and commentary, and Spacek does a great job with it.

(287) Badlands clip - Terrence Malick 1973 - YouTube

Music: There is a score, a fine one, by George Aliceson Tipton, but Malick also uses music by Carl Orff and Erik Satie. And then there’s the brilliant use of Nat “King” Cole recording of “A Blossom Fell.”

Humor: Somehow I had not realized before, or possibly not remembered, how much humor there is in the movie. Some of that humor comes from the dissonance between the narration and what is shown, and much comes from the 2 central characters and the disconnect between their self-image and what they do. But the humor never glamorizes their actions.

River: Is there a Malick movie without a river? On the banks of a river our couple make love for the first time (“Is that all there is?” she wonders. “Seems like a whole lot of fuss over nothing.” He doesn’t seem all that thrilled either.) They build a treehouse near the river and fish (and try to shoot fish) for food. The river sustains and nourishes, but it is from the far bank of the river than a man spots the young criminals, leading to the approach of the bounty hunters and the end of Eden.

Car chase: not usually the first thing that comes to mind when you think of a Malick movie, but the one toward the end of “Badlands” is masterful.

Magic hour shots: Why do you even ask?

| DAYS OF HEAVEN (1978). Viewed December 6, 2020. Five years later, his next movie. For this one Malick gets Best Director at Cannes. Not the last time. He has been less honored by Hollywood, to the shame of Hollywood. Actors: It was Richard Gere’s second movie and first starring role. Already he was thought to be a beautiful and sexy young actor, and certainly that works well for the part. His particular and somewhat modern beauty sets him apart in the movie, which is appropriate. He delivers a fine performance. Late in the movie the narrator mentions a “devil” in the house, and that devil is Gere’s Bill. |

| But the great revelation at the time is Sam Shepard in his first movie performance. I knew him as a playwright, and I’d seen enough photographs of him to know that he had an interesting, offbeat look. How brilliant of Malick to cast him as the rich and ailing landowner and wheat farmer. The camera adores his strange face with the odd planes and the mouth filled with crooked teeth and discovers |

Brooke Adams is perfect as Abby, love interest to Gere’s Bill, who passes her off as his sister when they leave (escape from) the eastern town where Bill has worked in a steel mill and where he had killed his foreman in a fit of rage. Her work as her boyfriend convinces her to engage the affections of and to marry The Farmer and then as her affections for her husband develop fit the movie perfectly. (Theorem: the basic plot could have served a 1940s noir.)

| And then there is Linda Manz, who plays a character named Linda who is Bill’s true sister. The narrative voice you hear is hers, and much of it was not written but was achieved simply by having her tell what she thought was going on in various scenes, resulting in some 60 hours of voiceover from which Malick and his editor selected what to use and where to put it. |

It is plain-spoken and reflects the nature of the character Linda. The apocalyptic musings as the immigrant worker train is on the way to the wheat fields is masterful, its images of insects and fire paying off wonderfully in the later locust invasion and wheat field fire against which tensions between the 2 male protagonists reach climax.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uBgwuM11q0o

In a way Linda could be viewed as the central protagonist and not simply observer. The opening credit sequence, which consists of a series of old black-and-white photographs of the working class and images of poverty concludes with a still of Linda in the style of what we have just seen. And the movie ends with her, as she, having fled an orphanage, and a young woman companion take off alone down the railroad tracks away from civilization. One might think of Huck Finn heading out for the Territories. Linda is more acted upon than actor in her life’s story, at least thus far, but now she is moving away from the brother who had protected her but also controlled mer. This may parallel the direction that Abby is now taking.

Music: That opening credit sequence is one section of the movie not scored by Ennio Morricone. For the opening Malick settled on ‘Carnival of the Animals” by Camille Saint-Saëns. Morricone received an Oscar nomination for his contribution, but lost. His score is wonderful, to no surprise, and at times it blends seamlessly with other sounds recorded for the movie, something I’m seeing as a Malick trademark.

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros brings a New Wave sensibility to a very American project, as Malick wanted. For his efforts he was awarded an Oscar. I can recall at the time criticism that the movie was “too pretty.” No. Simply beautiful. When he had to leave for another contracted project, Haskell Wexler was brought it to complete the film. Other cinematographers came in for a few added shots a year or so later. But the look of the movie is all of a piece.

There are magnificent landscapes and tiny details. A wine glass resting in a clear river. A crane walking in a burnt field. Sunlight through lace. A scarecrow in blue moonlight. Smoke bellowing from a locomotive engine. For me, at least, every image contributes to the totality of what Malick was reaching for.

Which includes: Urban vs. rural. The new industrial America vs. the vanishing West. Machines and people. Nature and progress. Best laid plans ganging aft agley. It is a rich movie richer every time I see it.

The plot: Does one think about plot in a Malick movie? Anyway, the situation is that Bill manipulates his lover Abby into marrying a rich farmer who he thinks is dying, but the farmer doesn’t die. Bad stuff ensues.

It interests me that the tale of Bill and Abby mirrors broadly the tale of Kit and Holly in “Badlands.” He kills a man and they flee, ultimately discovering an Eden in which they are, for the most part, happy. Another death, another flight. The law catches up with them, the man dying, the woman surviving.

“Days of Heaven” opens in an urban industrial setting, a steel mill. Most of the rest of the movie takes place on vast wheat fields. But when Bill and Abby accompanied by Linda flee from the farm, they go by river (!) and end up in woodlands beside the river and set up a camp, as Kit and Holly had done. The killer is spotted by a man from across the river, as Kit had been. There is a similar chase through the woods, but in the earlier movie Kit kills the bounty hunters while Bill is shot by the lawmen as he runs into the river. (Rivers are complicated in Malick’s work. Life, death, time . . .)

Some years back I began to sense that each of Malick’s movies seemed to grow organically from the one before and from his whole earlier body of work, actually. Kit/Holly and Bill/Abby are and early example of this in terms of plot.

Grass: All those wheat fields! The wind rushing through the wheat. There was tall grass in “Badlands” along the river where our couple had set up camp. Rivers and grass: they suffuse the collect works of Terrence Malick.

Nature: Here we see pheasants, grouse, buffalo, coyotes, ducks, and flights of birds overhead. And we see locusts. And fire. Yes, the fire was set by humans, but when it gets out of control it is nature. So is nature good? Bad? Neutral? This question will arise again as we move along.

| THE THIN RED LINE (1998). Viewed December 8, 2020. That date is not a typo. It really has been 20 years between Malick’s second and third movies. And this one is a biggie, large cast, things blowing up. It centers on the battle for Guadalcanal during WW2, but Malick being Malick, it is about so much more than that. The first words we hear from one of our several narrators: “This great evil, where's it come from? How'd it steal into the world? What seed, what root did it grow from? Who's doing this? Who's killing us, robbing us of life and light, mocking us with the sight of what we might've known? Does our ruin benefit the earth, does it help the grass to grow, the sun to shine? Is this |

This is definitely “The Tree of Life” territory.

That opening narration is in the voice of Private Train, played by John Dee Smith. Apparently Smith made only one more movie, “ER” in 1994. In 2005 he was a combat correspondent for the U.S. Marine Corp. Train has few scenes in the movie and seems not part of the action as shown. He appears in the mirror scene with Sean Penn early in the movie and aboard the departing ship at the end, reminiscing about his experience and what it meant. The accent is country, possibly Southern. His narration is marvelous, reflective, inflected by is religious upbringing. In a way it is the philosophical voice of Private Witt. Perhaps Malick thought it best to put that narrative thread in the mind of someone who survives the move, as Witt does not.

That narration is preceded by a shot of a gray-brown crocodile crawling into a green-scummed pond, which sets the color palate for the movie.

| But those 2 are not the only narrative voices we hear. Sean Penn’s Sergeant Edward Walsh has a lot to say, and in a way the movie is a dialogue between him and Witt. Nature vs. grace, perchance? Is Walsh the snake in Eden? Voiceover: We hear voiceover also from Lieutenant Colonel Gordon Tall (Nick Nolte), Private Jack Bell (Ben Chaplin), Captain James Staros (Elian Koteas), (Private First Class Don |

There is an overflowing cornucopia of noted actors in addition to those mentioned. Adrien Brody, George Clooney, Woody Harrelson, Tim Blake Nelson, John C. Reilly, John Savage, Thomas Jane, John Travolta, and other names that you would recognize. Some were relatively new at the time but have grown in stature since. All are fine, but I must sing out special praise for John Cusack as Captain John Gaff. What he does without words astounds, especially in his final scene with Nick Nolte. His face is the voiceover here. And I must tip my hat to Harrelson’s death scene.

“A child said What is the grass? fetching it to me with full hands;

How could I answer the child? I do not know what it is any

more than he.”

A poem full of questions and many attempts at answers, none complete in itself. And later in the poem,

“What do you think has become of the young and old men?

And what do you think has become of the women and children?

“They are alive and well somewhere,

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death,

And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the

end to arrest it,

And ceas'd the moment life appear'd.

“All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses,

And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.”

I suggest that the death of Witt and the transcendental moment immediately after is a filmic gloss on this passage. There are many deaths in this movie, and many of them have elements of the transcendent.

We will continue to see grass in Malick’s later movies.

Tidbits:

In the opening shot we see a crocodile entering a green pond. At the end of the primary battle we see a crocodile captured and trussed on the back of a truck. Is it wrong of me to think forward to Pocahontas in “The New World”?

The opening sequence of the movie finds Witt and a fellow soldier who have gone AWOL (not the first time for Witt, we learn) living among a group of native islanders. An Eden, from which they are captured and taken back to the ship. Much later in the movie Witt returns to this village and finds it no longer an Eden. Sores on children, flies everywhere, suspicious glances from the inhabitants. Has the village changed? Or has Witt been changed by his war experience? Edens lost, perhaps, can never be regained.

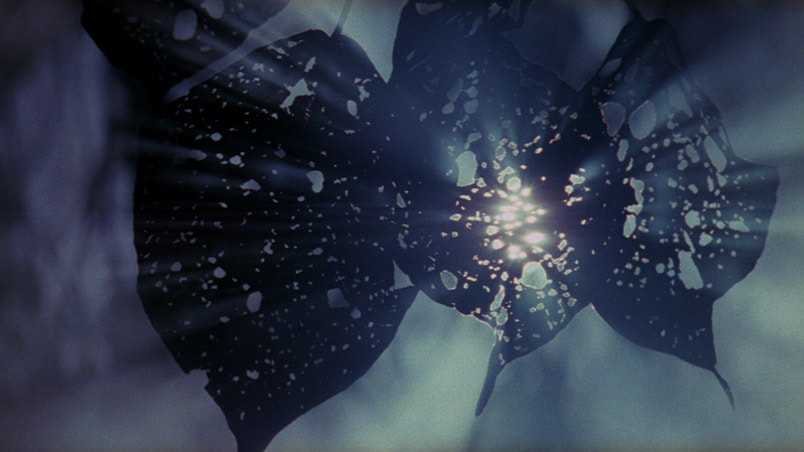

| Scenes of light shining through lace, sometimes real lace of dress and curtain in flashback, sometimes the lacery of trees and leaves. In a reverie early in the movie Witt reimagines his mother’s death and wonders whether when he meets his own death he will be able to exhibit her degree of grace. (I’d answer with a |

Malick does not judge his characters harshly. Nolte’s Lieutenant Colonel Tall could be construed as the villain of the piece in his insistence on taking the hill no matter the cost, even a comic villain at times in his rages, yet Malick allows for the possibility that he may be right and that there might be a tragic depth to the man. (Nolte is wonderful.) The truest villain is the Brigadier General Quintard, John Travolta, the next step above Tall in the chain of command. (I think in Malick the higher up the chain you are the more culpable you are.) The soldier seen blithely extracting teeth from dead (usually) Japanese is later shown breaking down in horror and shame at what he has done (the acting and direction both brilliant here). Marty Bell, who sends her husband the heartbreaking Dear John letter, is viewed with compassion and understanding, even love.

The wife soaring into the heavens on a rope swing hanging from a tree: compare with similar scene with Jessica Chastain in “The Tree of Life.”

Life as a prison. Witt is imprisoned in the brig early in the movie. Bell meditates that he had been in metaphoric prison until his wife’s love had liberated him.

Early shot of humans underwater, views of children swimming with light coming from above. Compare with the opening of “The New World.” Soon the idyllic opening is threatened by a boat on the water, viewed through trees. Again see “The New World.”

Watch how Witt watches. If Train (of thought?) is the voice of the Company, Witt is the eyes. So many shots of him seeing, observing, looking into.

In his brief appearance toward the end, George Clooney as Captain Charles Bosche in a speech to men under his command compares himself with the Father and Sergeant Walsh as the Mother. Should we then think of Lieutenant Colonel Tall as Father and Captain Staros as Mother? Mother will become increasingly important as we move along through Malick.

The score by Hans Zimmer is lovely, more mournful than action-oriented. Extant music by Gabriel Fauré (his “Requiem”) and Charles Ives are used to great effect. The Ives piece is “The Unanswered Question,” a perfect choice for this movie for any number of reasons.

The closing image:

“The Thin Red Line” begins with scenes of nature: crocodile, trees, vines, light through leaves. Next we see scenes of daily life among the indigenous people of Guadalcanal. We see children at work and play, and then ravishing shots of children swimming in the ocean, shot from below, with Witt happy above in his canoe. A military boat arrives, shot through the trees, alarming our 2 AWOL soldiers. Then a lingering shot of a ship at sea, and we discover Witt in the brig, his face emerging from the dark.

“The New World” begins with a pre-credit sequence of water with philosophic musings on the voiceover. After the credits we are underwater looking up, with swimmers, young adults this time, above us. We cut to a ship, first seen from a distance. Then we discover John Smith in the brig, his face emerging from darkness. From the land indigenous people look out through trees to the 3 ships.

The English refer to the people they discover as “naturals.” I love that.

In “The Thin Red Line” Witt is imprisoned in the brig for desertion. In “The New World” Smith is imprisoned for an unexplained charge of mutiny. In each case the prisoner is released to take on a new task, Witt to become a stretcher-bearer, Smith to go upriver to check out possibilities for trade. Witt had been pulled from his Eden when he was captured. Smith discovers his Eden with his Pocahontas while living with the Naturals for a time but must return to his own tribe.

Pocahontas is played by Q'orianka Kilcher, who was 14 at the time the movie began filming. She is wonderful in the part. No doubt her age contributed to the care and delicacy with which the love scenes were shot. She works beautifully with her John Smith, played by Colin Farrell in a performance that seems greater every time I watch the movie.

| The other significant performance is that of Christian Bale, who portrays John Rolfe. Bale has been one of my favorite actors ever since “Empire of the Sun,” and here he makes a truly good and kind man believable and eminently watchable. In a way it is the opposite extreme of his performance in “American Psycho” and far from his conflicted Batman in Christopher Nolan’s trilogy. |

Pocahontas becomes the central character because it is her fortunes we follow. She loses her home, her tribe, her land, and her first love before ending up in England, where she dies young. She has throughout been seeking her “Mother,” variously in the sky, the river, the grass, and at the end she seems to find the Mother and herself and is at peace.

Grass again. When first Smith registers her presence she is emerging as if a spirit from the grass. Their love takes place primarily in grass. One of the visual jolts in the movie is that at the estate in England where she lives out her final few years there is not grass but manicured lawn, not trees in the forest but green growths clipped and shaped by man.

And birds! Someday someone is going to tally the shots of birds flying in Malick movies.

Captain John Smith is the only one of the invasive force who senses great possibility in a New World. His meditations on possibilies haunt, and we are saddened because we know how things turn out. Possibly his saddest musing is about the failed chance of the settlers to work with the Naturals and learn from them and create a new kind of society along with them.

Powhatan and his advisors (wisely) want the English to leave. The greatest betrayal of Pocahontas of her tribe is her giving the English corn to plant, the act leading to her expulsion. Powhatan sends one of his primary advisors (in the fabulous form of Wes Studi) to England on the same ship that takes Rolfe and Pocahontas, his charge being to make a notch on his bundle of sticks for every Englishman he sees. There are many more notches than sticks.

The Prelude to Wagner’s “Das Rheingold” is used for the opening and closing of the movie. You’ll hear Mozart’s “Piano Concerto No. 23” and other pieces of extant music in addition to James Horner’s score composed for the movie. All of it is used magnificently, but that is something I’ve become accustomed to with Malick by this time.

Watching Pocahontas as she moves from being a Natural to a hostage, watching as she is groomed into being an acceptable member of the pioneer community and wife to John Rolfe, and watching as she becomes an English lady is one of the saddest progressions I have experienced in movies. What saves the watcher from despair is her growing in self-knowledge at the end. And then she dies.

The whole last section of the movie, after her final goodbye to John Smith to the end, is incredibly moving to me. She and Rolfe are on the way back to the New World when she dies before leaving England, but the movie and we the audience continue on back to the New World, to a river and a waterfall. Music, no narration, and at the very end the music stops and we here only the sound of water and the call of a bird.

(358) Terrence Malick's The New World - Final Scene - YouTub

I always watch “The Tree of Life” close to Christmas, along with Terence Davies’ “The Long Day Closes,” George Balanchine’s “Nutcracker,” and (usually) John Huston’s “The Dead” (yes, I know that last is really a Twelfth Night movie, but it still works for Christmas).

| Birth. Death. Transfiguration. Memory. The beginning all things and the end of all things. Growing up in a Texas town in the middle of the last century. Husbands and wives. Fathers and sons. Mothers and sons. And, famously, Nature and Grace. |

Some have found it difficult to get into, its meanings obscure. Some had said the same thing about the much earlier “2001, A Space Odyssey.” I had no difficulty with either. As in “Hamlet,” if you sit back and watch and attend and listen and enjoy, on first viewing you get it. And then, every time you experience it you see more in it.

“The nuns taught us there are two ways through life: the way of nature and the way of grace. You have to choose which one you'll follow. Grace doesn't try to please itself. Accepts being slighted, forgotten, disliked. Accepts insults and injuries. Nature only wants to please itself. Get others to please it, too. Likes to lord it over them. To have its own way. It finds reasons to be unhappy when all the world is shining around it, when love is smiling through all things. They taught us that no one who loves the way of grace ever comes to a bad end. I will be true to you. Whatever comes.”

Those are the first words we hear, voiceover spoken by the mother, Mrs. O’Brien (Jessica Chastain). She seems to be thinking back over her life, and we see images of her as a young girl. We see a telegram being delivered, the messenger almost running away after she takes it. It reports the death of her son. She calls her husband at work with the news, which we don’t hear because of the noise of an airplane.

| But is that opening sequence reportage or memory or reflective invention in the mind of Jack, the oldest of 3 sons, a middle-aged man, a successful architect, decades later? I’d suggest that everything we see and hear in the movie comes from Jack: his own present musings and the voiceovers of his mother and father and of himself as a pubescent boy. |

And what a reverie it is! It includes everything from the Big Bang to the end of the Universe with a lengthy stopover imagining his birth and early childhood.

It is those cosmic extensions that seem to cause some viewers difficulty. Some want to see the tale of boys growing up in a Texas town as the movie, and this other stuff is a distraction. I, for one, consider that other stuff crucial

The micro within the macro: what do our lives mean when measured against the vastness of time and the universe? Measured against, if you will, God?

| There are those who view the brilliant final sequence as a failed attempt to show Heaven or the Afterlife. They think it would be a boring place to spend Eternity. From my first viewing of the movie at an out-of-the-way movie house in Birmingham (the closest venue I could find, 2 hours away), I never viewed the sequence in that way. For me it was a reverie, a dream, a meditation, a poetic evocation of acceptance |

I never tire of this movie. I have watched it at least once a year since 2011, and every time I find more in it, a detail, a linkage, a parallel. There are still wonderful and magical images that haven’t revealed fully their meaning: I think of a black face mask as if left over from a carnival sinking down through water. Not being plot driven, the movie constantly seems new and surprising. Most movies are like novels or short stories: situations, development, surprises, conflict, resolution. “The Tree of Life” works more like music, or poetry, or dance.

The Book of Job makes another appearance in the middles of the movie in a sermon by a priest to his congregation:

“Do you trust in God? Job too, was close to the Lord. Are your friends and children your security? There is no hiding place in all the world where trouble may not find you. No one knows when sorrow might visit his house, any more than Job did. At the very moment everything was taken away from Job, he knew it was the Lord who had taken it away.

“Job imagined he might build his nest on high. That the integrity of his behavior would protect him against misfortune. And his friends thought mistakenly that the Lord could only have punished him because secretly he had done something wrong. But no. Misfortune befalls the good as well. We can't protect ourselves against it. We can't protect our children. We can't say to ourselves, even if I'm not happy, I'm going to make sure they are. We run before the wind, we think that it will carry us forever. It will not. We vanish as a cloud, we whither as the autumn grass. And like a tree, are rooted up.

“Is there some fraud in the scheme of the universe? Is there nothing which is deathless? Nothing, which does not pass away? We cannot stay where we are. We must journey forth. We must find that which is greater than fortune or fate. Nothing can bring us peace, but that.

“He sought that which is eternal. Does he alone see God's hand, who sees that he gives? Or does not also the one see God's hand, who sees that he takes away? Or does he alone see God, who sees God turn his face towards him? Does not also he see God, who sees God turn his back?”

No particularly comforting words, but then the Book of Job is not noted for that. In the beginning of this sermon we are looking into the face of the priest. The latter parts are played over images of Jack and his brothers being mischievous in the church after the service, stepping from pew to pew, and riding in the family car as they drive away from the service.

One criticism of this movie that I found interesting complains of its Christianity-centric approach, as if Malick is preaching from that viewpoint. To me that viewpoint perfect, echoing the society and the teachings in which Jack is raised. Its specificity is what makes it have an appeal more universal. We’re dealing with mid-twentieth- century small-town Texas here. There well might be a Jewish congregation nearly, but I doubt a Muslin or Buddhist temple. There might have been a bit of New Wave thinking, but as in my region of Alabama it would likely have been hidden beneath adherence to mainstream Christian faiths.

| Jessica Chastain is Mrs. O’Brien, her first significant movie role and, for my taste, her absolute finest. She has had a substantive career since, and she has credited Malick with helping make that possible. That red hair, that pale skin, that face with unusual planes, she is strangely beautiful. Great movie beauty is often strange. I think of both Hepburns, Garbo, Huppert, Sam Shepard even, and Rutger Hauer. |

And the 3 boys. Laramie Eppler plays R.L., the brother who dies at 19, possibly by suicide. I believe that this is his only movie performance, but this movie will take his name down the years. Tye Sheridan plays Steve, the youngest of the three brothers. He has the least amount of screen time, but he has gone on to other projects including “Mud,” “Ready Player One” (the lead), and a couple of the X-Men movies.

| Jack as a young boy is played by Hunter McCracken. All the boys do fine work, and McCracken is spectacular. Had he not been, the movie would have been far less great. In a sense he is the star, and Pitt, Chastain, and Sean Penn (older Jack) are the supporting actors. It will be a shame if this turns out to be his only performance. This is as good a place as any to acknowledge how wonderfully Malick works with young actors. Manz in “Days of Heaven. Kilcher in “The New World.” And these 3 boys in “The Tree of Life.” But he does well by the more mature and the tried-and-true: here I think of Fiona Shaw and now marvelously she comes across as the Grandmother in barely a minute of screen time. |

The young Jack seems to me to be connected with Kit in “Badlands,” Bill in “Days of Heaven,” Witt in “The Thin Red Line,” and Captain John Smith in “The New World.” All are young and in various ways rebellious, although their ways of rebellion are significantly different. Is he, are all of them, also connected with Terrence Malick? The director had a brother who played the guitar, quite well, apparently, who died at 19, probably by suicide. Malick too grew up in small-town Texas. I suggest that his entire approach to filmmaking is rebellious in the multiple ways he goes against the norms of that calling and endeavor.

But in “The Tree of Life” he doesn’t present us with his autobiography. Rather, I believe, he has used personal elements from his life in a new fiction to explore ideas and concepts, beliefs and possibilities. He is, you recall, a philosopher before he becomes a filmmaker.

In the first 3 movies the protagonist dies. In the fourth he ends up older and sadder and wiser. In “The Tree of Life” the older Jack has become a successful architect and a man of means. He has fought through to success in life, but he still finds himself torn by the problems of his younger life. As these memories and emotions and conflicts and love flood through his soul, he seems to find if not answers to the great questions at least some sort of acceptance and reconciliation. And maybe that is the best we can hope for.

Viewed December 18, 2020

In 2018, courtesy of the Criterion Collection, we get to see new extended version overseen by Malick and featuring an additional 50 minutes of footage. It is wonderful material, beautifully crafted in every way, wonderfully edited together and incorporated into the original work.

That being said, the longer version must be viewed as supplement to the original, which Malick himself said is the true and preferred version.

Among the new material is a bit more of the family’s interaction with neighbors. We see more of Mr. O’Brien’s callousness toward his family, unnecessary. We meet Mrs. O’Brien’s brother, who also suggests grace ad certainly manages to interact with the 3 boys more positively than their father. There is a great storm sequence and its aftermath, but I can see why it as cut: it detracts from the storm within the soul of Jack. We see young Jack being encouraged in his rebelliousness by another boy, one more seriously abused than Jack: this detracts from Jack’s own story, it detracts from the focus. We see more of Jack’s problems at school, parent/teacher conferences, a decision to send Jack to a private school some 100 miles away. Throughout the middle section of the movie there are slight additions to many of the sequences. All of this material both over-explains and weakens the thrust of the original cut.

If only the extended cut existed I would think it was an excellent movie, but it would not be nearly as high in my regard as the original version. I somehow suspect that one of Malick’s motivations for the longer cut is to show more of the excellent work of his cast and crew, and that is excellent enough to deserve this presentation. I do much prefer to see the extra footage in this way than in isolated outtakes. I’m glad to have it in my collection.

Often when I watch “The Tree of Life” (and most other works of Malick for that matter) I think of William Wordsworth and his “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.” I know it is fashionable to dismiss the poet and particularly this poem, but I’m not led too much by fashion in my loves.

Ode: Intimations of Immortality from… | Poetry Foundation

* * *

For me, there is a line through Malick’s first 4 movies pointing to and climaxing in “The Tree of Life.” I imagine that for me this will be his greatest work, his masterpiece. Where does the hunter go after tackling game as large as he does here? Possibly one scales down. Possibly having set the major theme he elects to do variations. Whatever, for me his later works continue to fascinate.

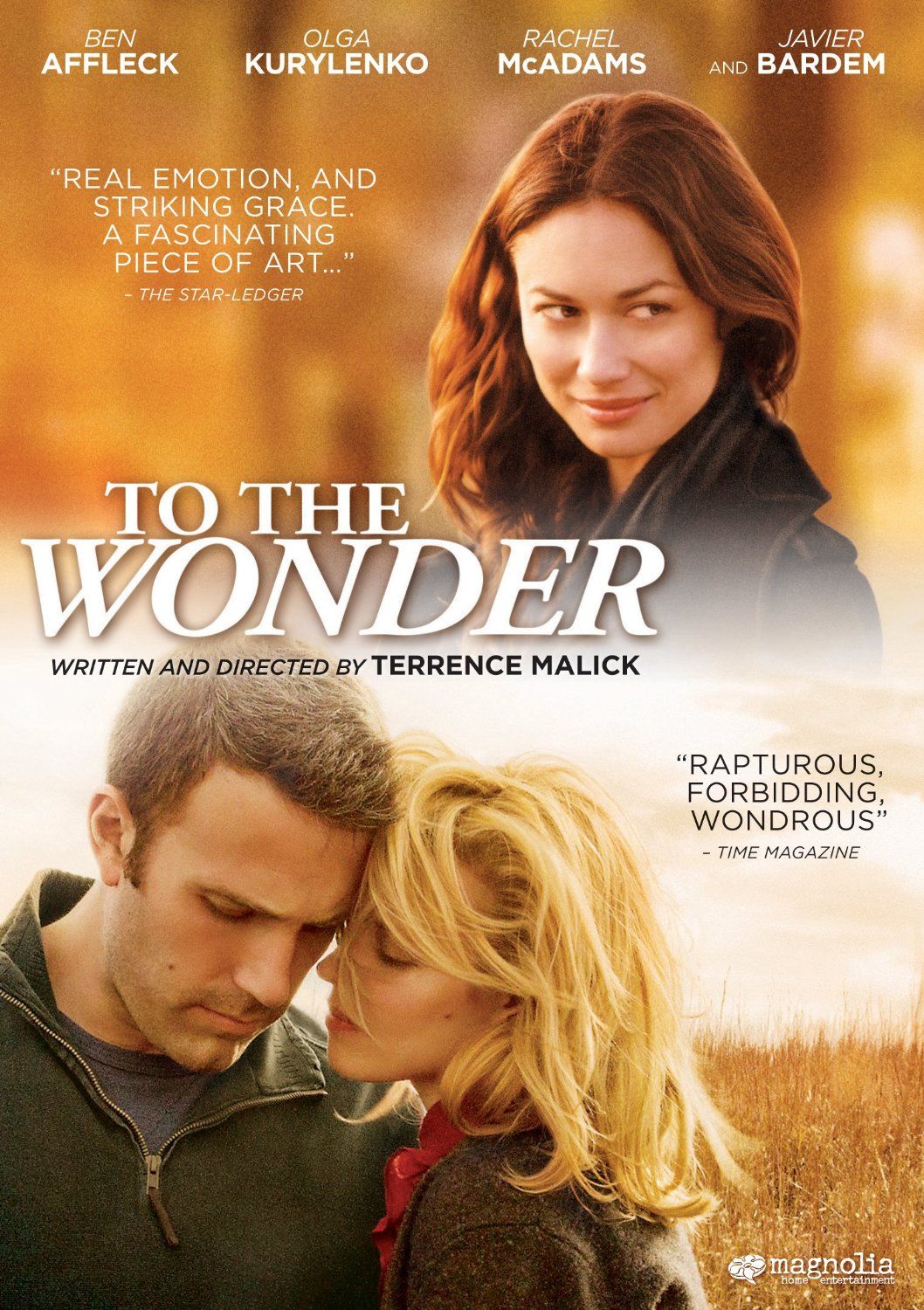

| TO THE WONDER (2012). Viewed December 20, 2020. If The Tree of Life” is like, say, a grand opera or a concerto grosso, “To the Wonder” seems more like a chamber piece. The former has great sweeping gestures that pull you in and keeps sweeping you along. The other you have to sit there and attend to its images and compositions and contrasts and make your own judgments as to what it is about. At times I think of poets like T.S. Eliot and at times I think of Picasso’s cubist paintings. It is a movie composted of fragments, I believe. What you make of those fragments may depend on you, your life experiences, your patience as you worry those fragments, and the present time of your viewing it and your mood while doing so. And that I don’t mean as criticism but as description. |

| If you struggle too hard with it you will likely become lost. The basic “story,” such as it is, is fairly simple to get in broad outline. Marina (Olga Kurylenko), a single woman in France with a 10-year-old child Natasha, falls in love with an American, Neil (Ben Affleck). Mother and daughter return to |

Then ambiguity enters (oh, you thought it was already there?) particularly in the form of a child, a young boy. Marina’s? Jane’s? An actual child? What might have been? And Marina on the western plains: A memory? Or has she returned?

Ya pays ya money, ya takes ya choice.

Throughout the movie one sees glimpses of the kinds of problems that can arise as First Love is cooled by the passage of time and life and as the participants cannot (yet?) manage the mature growth necessary to accommodate them. There is an interesting comment from Neil that he is

When the child Natasha starts to become unhappy in her Oklahoma surroundings she complains that something is not right, we both need to leave. Neil in his work finds dangerous chemicals in local streams from construction work, and folks who live nearby tell him that they don’t feel well and sometimes tar oozes up in their yards. Father Quintana is dealing with people in poverty, but once he seems to hide from someone seeking his aid. Something seems rotten in the Heartland. My sense is that Malick has a great love for his country and his region but is far from blind to its problems and its faults. And its history.

The promise that Captain John Smith dreamed of in the New World has, if not vanished, been seriously broken.

I see possibly 3 strands interwoven throughout.

A movie director is being urged to make a new film even though, it seems, he did not complete his last one.

A man is remembering the women he has loved, and, it appears, he still loves them all.

An aged father and his oldest and youngest sons still trying to deal with the death of the middle brother, possibly a suicide, some years earlier. (Did I mention “The Tree of Life”?)

At times I think of “L’Aventtura,” “Lo Notte,” “La Dolce Vita,” and of course “8½.” But ultimately it is different from any of these. I’ll bet anything that Malick knows them.

| Ever since “Empire of the Sun” I have loved Christian Bale as an actor. Something about him sings to me. He is in almost every shot in “Knight of Cups, and the camera caresses him. He says so much by saying so little. And he watches wonderfully. Among those beautiful women he watches and loves are Cate Blanchett, Natalie Portman, Teresa Palmer, Imogine Poots, and Frieda Pinto. Wes Bentley |

If ”The Tree of Life” centered on Jack’s relationship with his mother and his brother, “Knight of Cups” centers on Rick’s relationship with his father. Joseph, the father, says at one time that his son is like him. Rick is grateful for the courage and strength he got from his father. Rick, like so many others in Malick’s work, is a fragmented soul, and the thrust of the movie is about his putting the fragments together. Part of that reconciliation is with his father.

This may be the most divisive of Malick’s movies. I now definitely know on which side of the divide I am on. I wasn’t sure how much I liked it until this latest viewing, right after having seen all of the director’s work up to this point. Any artist worthy of that name teaches you how to look at the work, whether the artist is Vincent Van Gogh or Emily Dickinson or Pablo Picasso or George Balanchine or William Faulkner of Terrence Malick.

The image and imagery captured by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki are fantastic, and the selection and juxtaposition of them in the editing process is unexpected and startling, and for my tastes, wonderful. This is the fourth time in a row that Lubezki has worked with Malick, and he will also shoot Malick’s; next movie. The 2 wonderfully capture both well-known and little-known areas of the Greater Los Angeles area in ways I have not seen before, and what they do with Los Vegas is nothing like you have seen before of that town. Suggestion for future study: the mutual influence of the two on each other. But I’ll let someone else tackle that one.

There’s a lot reminiscent of earlier Malick movies: magic hour shots, natural lighting, shots through windows and curtains, camera underwater looking up (and I particularly liked the dog jumping into the water after a ball, trying to catch it). The rocky desert where Rick wanders reminds me of the barren rocky wasteland through which the older Jack wanders in “The Tree of Life.” A priest ponders the role of suffering. There’s a lot not normally associated with Malick: pole dancers, big party scenes, movie backlots, freeways. For me it all works together.

Lots of tarot references. Lots of literary references including “Pilgrim’s Progress” and the apocryphal Acts of Thomas, but I’ll not venture into all of that (but feel free to search them out is that is your desire). I did check out the tarot card from which the work gets the title, and while that was not necessary it did suggest to me that I was not incorrect in my interpretation of the movie.

Sometimes it is hard to explain love, whether of another or a work of art. Theodore Sturgeon, that great writer of science fiction and fantasy of my earlier years, once wrote “Why must we love where the lightning strikes and not where we choose?” The lightning strikes me with this movie, in a way that it did not for the earlier “To the Wonder,” like it and admire it thought I do.

| SONG TO SONG (2017). Viewed December 29, 2020. Hard to get my head around this one. Now that doesn’t mean that I don’t like it, for I do. Malick tends to work in fragments, which he then assembles magically into a whole. I’m not sure this one gets all the way there. It may take more viewings over time to sort it all out. (As if one can ever sort Malick out. Part of his charm.) I get the basic story, such as it is. Faye (Rooney Mara) is in a relationship with Austin record producer Cook (Michael Fassbender) hoping that will jumpstart her career. She meets aspiring songwriter BV (Ryan Gosling), also working with Cook, and falls in love while maintaining her ongoing liaison with Cook. Cook becomes aware of the love affair and seems to encourage it, until he doesn’t and the |

Cook falls for Rhonda (Natalie Portman), a practicing Christian former kindergarten teacher who jad begun working as a waitress to pay the bills. Rhonda finally becomes unhappy with her life with Cook (sex, drugs, rock-n-roll and all that) and drowns herself, leaving Cook bereft. Faye ad BV find each other again and seem to be headed for a happier and simpler life away from the music scene.

It interest me that Faye enters into a same-sex relationship. What about Cook and BV? Initially they seem to be friendlier than mere friends, with lots of physicality between them. And two buddies sharing the same woman often has been used to signify a homoerotic relationship in movies. Add to that actors like Fassbender and Gosling who both exude sensuality and sexual boldness, and the thought cannot help but cross one’s mind.

I am trying to decide whether the movie is too long or too short. Perhaps the Fassbender/Portman matter should have been reduced (but then again it is so good). Or maybe it should have been built up more, to better counterbalance to the Rooney/Gosling relationship. Do we need to see BV with his two brothers and hear about their difficulties with their father and later see a deathbed reconciliation scene were BV forgives is father? If kept, perhaps it needed to be emphasized more.

But don’t let me second guess Malick. I think it was Cleanth Brooks who said way back in the middle of the last century that to approach William Faulkner you had to assume that he knew what he was doing and your job as critic was to figure out what that was. So I will just let “Song to Song lie there for a while and then I’ll tackle it again.

Whatever, it is filled with gorgeous images and sequences. And music.

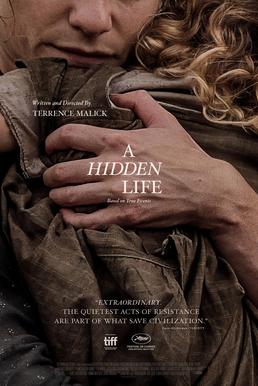

| A HIDDEN LIFE (2019). Viewed December 30, 2020. The closing title card is a quotation from George Eliot’s “Middlemarch.” “...[T]he growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.” The story is simple. Austrian farmer Franz, married to Fani and father two 3 daughters, becomes convinced of the moral wrong in Hitler and his invasion of other countries. In spite of entreaties from community and church he refuses to participate in the German war effort. When he is inducted, his first action is to |

A fool? A saint?

The story could be told in a scant hour and a half. Malick’s movie runs nearly 3 hours. For me, not a moment is waste. He slows tings down to make you think about them. There are questions addressed to Franz thoroughout, along with much advice. We linger over each one and are given time to consider. What should Fritz do? What should I do?

What do you think you will accomplish? You won’t hurt the war effort at all. You are hurting your community, your neighbors, your family including your sister-in-law and your mother, who live with you. The ultimate advice from his church: God will know what is in your heart so if you have to lie to survive He will understand. Ultimately his fate rest on one possibility: Accept a job working in a hospital and as long as you swear allegiance to Hitler all will be forgiven. But Franz cannot swear allegiance, give the salute. A fool? A saint?

The prison interiors are beautifully designed and filmed. They are not pretty, but they become beautiful. Like interiors in Rembrandt.

Except . . . If I had come upon the movie knowing nothing about it, might the name Aleksandr Sokurov have come to mind? More than once I thought of his magnificent family sagas “Mother and Son” and “Father and Son.” Both the look of the movie and the approach to the characters suggested to me an affinity.

“A Hidden Life” is set in the mountains of Austria before the middle of the last century, but in my heart of hearts I know Malick has been looking at his own country for the last few years.

One critic (at least) has complained that the movie is too much involved with the moral struggles of just one lowly Austrian man and ignores the Holocaust. But it seems to me that Malic looks at little things. He knows that the Holocaust is going on, but it is likely that he sees even that as the culmination of little people making their own little moral decisions.

Toward the end of the movie, the judge at the final trial speaks with Franz alone in an attempt to sway him from his course of action. There is this exchange:

Franz Jägerstätter: I don't know everything. A man may do wrong, and he can't get out of it to make his life clear. Maybe he'd like to go back, but he can't. But I have this feeling inside me, that I can't do what I believe is wrong.

Judge Lueben: Do you have a right to do this?

Franz Jägerstätter: Do I have a right not to?

A hard question that Franz asks.

Franz and his family suffer greatly, and one might ask was it all for nothing. I don’t believe that the Book of Job is cited directly in this movie, but for me it hovers. Comfort comes hard, if at all. But as Fani’s father says to her, “Better to suffer injustice than to do it.”

A fool? A saint? The Catholic Church has decided that the real Franz Jägerstätter is the latter.

Technically the movie is superb. Most of the background chatter is in untranslated German, with English used for intimate conversation and intimate thoughts and when a pertinent question or comment is thrown to Franz, as at the trial or in private conversations with fellow prisoners or those keeping them prisoner. The music (lots of great German composers here) is always right and, I think, never overpowering. I see an artist at work at the peak of his craft and his art.

There is an artist as a character within the movie, one who paints frescoes and ceilings of the church. He has this to say: “What we do, is just create... sympathy. We create-- We create admirers. We don't create followers. Christ's life is a demand. You don't want to be reminded of it. So we don't have to see what happens to the truth. A darker time is coming... when men will be more clever. They won't fight the truth, they'll just ignore it. I paint their comfortable Christ, with a halo over his head. How can I show what I haven't lived? Someday I might have the courage to venture, not yet. Someday I'll... I'll paint the true Christ.”

Which leads us to Malick’s next movie, now in post-production.

We don’t know much about it. IMDB describes it as “A retelling of several episodes in the life of the Christ.” I have also read the suggestion that it tells the life on Christ in terms of some of His parables. Its original title was “The Last Planet.” Some unnamed person from the production has been quoted as saying “the film is about humanity, starting from the Big Bang to the Apocalypse.”

Sounds like a summing up.

We can expect to see G Géza Röhrig as Jesus Christ, Mark Rylance as Satan (he has said in an interview that he plays 4 versions of Satan), Matthias Schoenaerts as Saint Peter, and Aidan Turner as Saint Andrew. Other actors in the cast include Ben Kingsley and Joseph Fiennes.

Whatever else, it will be a Terrence Malick movie. If still alive I will see it. Prediction: it will divide critics and audiences, and I will love it.

I think back on what that artist said in “A Hidden Life.”

“Someday I'll... I'll paint the true Christ.”

I’m not sure that is something the present world wishes to see. But I do.

AFTERTHOUGHTS & RUMINATIONAS

* Totally by accident, on New Year’s Eve I experienced an epiphany of sorts. I was watching the Terence Davies movie “The Long Day Closes” (something I do every year close in to New Year’s Day), and for the first time I noticed that the mother’s maiden name was O’Brien, the name of the family in “The Tree of Life,” spelled the same way. This brilliant movie was released in 1992, during the 20 year hiatus between Malick’s second and third movies (“Days of Heaven, 1978 and “The Thin Red Line,” 1998). Is it possible that seeing the Davies movie helped jumpstart Malick again creatively? So much in “The Long Day Closes” is echoed in Malick’s later work: shooting into light source, use of extant music, realistic settings treated fancifully, shooting through windows and doorways, light through curtains, the present measured against eternity. If this speculation is correct, it in no way diminishes Malick’s work. Great artists are often influenced by other great artists. The two filmmakers are much of a generation, Malick born in November 1943, Davies in November 1945. My generation too, in a way, although I’m 4 years older than Malick.

*Music. Malick’s use of music is rich and complicated and deserves thorough scholarly study by someone who knows movies and who knows music. The Creation sequence in “The Tree of Life” is often compared, aptly, with Stanley Kubrick. Yes, but more apt is the use of music throughout the work of both directors.

*Performance. Malick likes the natural and the unexpected. He is likely to give actors a general description of a scene instead of a detailed script and then let them improvise. He does not block, instructing them to hit a specific mark at a specific time. He works with a small production crew and can change immediately what he wishes the camera to look at. Actors must remain always in character, for he might suddenly focus on any one of them. Some actors respond well to this, some less so. I think he ends up with remarkable performances, including from children.

*Responding to the moment. With a flexible and small camera crew Malick can capture the unexpected. A prime example: Mrs. O’Brien chasing a butterfly in “The Tree of Life” and the butterfly landing on her hand. Not a special effect. A real moment that Malick saw happening and had the cameraman shoot. Now I also admire the carefully planned movie, something like “Avatar.” It is not whether by accident or by design but whether the result works and can, perhaps, end up as art.

*Editing. Often Malick takes a year of so editing his movies. I think of the process of shooting his movies as Malick’s assembling the clay for a sculpture and the editing process as his shaping the raw material into art. He is not like, say, Hitchcock, who knows exactly what he wants and shoots only exactly what he needs. For me, neither process is better or worse. Whatever works.

*Repeating images. Water: rivers, streams, waterfalls, oceans, underwater shots looking up. Grass: wild grasses blown in the wind, cultivated fields of grain, lawns with weeds or not. Trees: of Life and otherwise. Birds, in flight and on the ground. Other wild animals and tamer animals such as horses, cows, and buffalo. Doors. Windows. Stairways and ladders. Roads and paths. Light shining through fabric. Angels (for want of a better word). Candles. Fire. The sun. But don’t think you can assume that river = x and grass = y. Their meanings are fluid. Water can be a place of birth or death. It can wash away sins or hide transgressions. It can bring the despoiler to Eden.

*Criterion Collection. Criterion has presented Malick’s first 5 movies in wonderful editions. Each has intriguing extras and interviews with cast members and crew (production designer Jack Fisk is particularly good here), but no sign of the director himself. He hides. “The New World” edition offers all 3 versions of the movie: the Cannes cut, the American release cut, and Malick’s later extended cut. One of these days I’m going to watch all 3 close together, for I understand that is a master class in how editing can shape or change a scene and the work as a whole. “The Tree of Life” set contains both the original ad the extended cuts. I hear rumors that there may be extended cuts of the modern-day trilogy between “The Tree of Life” and “A Hidden Life,” and I wonder if perchance they will be coming from Criterion. If so, I’ll be first in line to purchase them.

*Summing Up. I warned you at the beginning that this was a love letter, not a critique. You don’t remember loves by nitpicking about the object of your affection. My true audience is myself. December 2020 will always be remembered as my Malick Month. (Not much else positive can one say about that month, or the whole year, for that matter.) All the discs have been returned to their shelf, and it is unlikely that I will ever watch every one of them again in one month. But I will be watching every one again. No doubt every time I will discover new wonders.

*Images.

All Things Shining. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dE2Bgn2iGgI

More images: (357) A tribute to Terrence Malick's visual poetry - YouTube

And more, grouped thematically: (357) Best Shots Of Terence Malick - YouTube

The “modern” trilogy: (357) Malick's Obsessions - YouTube

Images and philosophy: (357) Transcending Heidegger – The Cinema Of Terrence Malick - YouTube

RSS Feed

RSS Feed