| I do love David Fincher. What follows is more a love letter to him than a detailed critical analysis. That being said, I would not love him so much had his work not satisfied some critical creature lurking in my brain. That detailed analysis I will leave to someone with more time and knowledge than I have, and certainly there is a lot in Fincher’s work deserving such attention. Some of that I |

The color palette: reds, yellows, browns, grays, blacks. The framing of actors in scenes. The brilliant use of close-up, the angle often from below. The care taken with performers, including those in lesser roles. And I continue to believe that Sigourney Weaver’s performance as Ripley in the four movies is one of the signal female performances of that whole period, and she is especially good in Fincher’s contribution. The man is great with actors. And of course, the darkness.

I have the Alien Quadrilogy on Blu-ray and I haul it out and watch it every few years. Increasingly I find that Fincher’s contribution (especially in the longer cut) holds up better than James Cameron’s Aliens - the second in the series. Yes, Aliens is a more accessible film, since it is basically an action story, but Fincher’s engages the mind and the emotions better. Or so I think.

The theatrical release version runs just under two hours, the extended cut (2003) maybe a half hour longer. That longer version is presumably closer to what Fincher wanted before control was taken from him and is the one I usually watch. For this piece I re-watched both versions the same day, the shorter one first. So much of what I love about Fincher is there. No surprise that, for I had loved Alien 3 from the beginning.

There are significant differences. In the 1992 cut spaceship escape pod crashes, Ripley is dug out of the wreckage by workmen and is dumped onto an examining table. In the longer cut, after that crash we see lingering shots of the exterior of the prison planet, the abandoned machinery on the surface, the lumbering stolid oxen used as work animals and as food. Clemons, the doctor, is walking on the beach and finds Ripley’s oil-covered body lying at the edge of the sea, picks her up, and takes her inside after ordering the workers to look for other survivors (they find none). These grim exterior shots beautiful in their own way as is so much of Fincher, set us up for the interiority and claustrophobia of the rest of the movie. And one of the oxen becomes the first host for the alien lifeform.

The oxen have disappeared from the shorter cut. A dog, a Rottweiler, becomes the first host. Again, the emergence of the first creature is intercut with the funeral (which anticipates the end of the movie) of the two humans who had died in the escape pod, Ripley’s daughter-equivalent and possible boyfriend. I have problems with that dog. Why is he on the prison planet? Why is he the only one? And why is there no sorrow over his loss? I prefer the use of the ox, a beast of burden destined to be carved up for the table. I don’t know whether the dog footage was done by Fincher of done by someone else, but it is a point for some future scholar to tease out.

A second significant change occurs during Ripley’s ultimate act of rebellion at the end. The shorter cut has a chest-burster emerging from her, the longer one does not. Again, for me the longer cut choice is preferable and somehow sets up the coda movie (Alien Resurrection) more effectively.

There are small cuts throughout the shorter version to tighten the movie, but tighter is not always better. But the most significant involves Golic, the man who sees two of this compatriots slaughtered and survives only to be thought a crazed murderer and constrained in a straightjacket. In the longer version he prevails upon a fellow prisoner to release him, after which he lets loose the beast who had been contained by Ripley and the crew. I’ll return to Golic and that action later.

Also significant is that the cumulative effect of the cuts in the shorter version diminishes the importance of the prison’s religion. For if this is not exactly a movie about religion, it definitely uses religious imagery.

A savior descends to the planet from on high.

That savior sacrifices herself to save all mankind.

Interior set design is reminiscent of a medieval monastery.

The circular openings in the main set where meetings religious and otherwise take place remind one of rose windows in cathedrals.

The 25 remaining prisoners have taken a vow of chastity (“And that includes women”).

The android Bishop, like Lazarus, is raised from the dead by the savior figure. His name takes on added significance because of the religious imagery.

Golic, the crazed man who sees the Alien kill his two buddies and is himself blamed for their deaths, comes to think of the creature as the Devil, becoming in effect a devil-worshipper.

Composer Elliot Goldenthal’s score has a religious emphasis and uses choir voices.

The movie was criticized, much of that criticism deflected onto the director, for killing off the only two other survivors from “Aliens” and doing so in the opening credits. I thought doing so was brilliant: we had seen Ripley and Hicks falling in love in “Aliens,” their primary physical contact being his showing her how to use weapons, and we certainly had plenty of the child Newt being saved by the mother figure. It was not a departure for Ripley to lose a child between movies. It had happened before after “Alien.” A sudden thought: she loses a child at the end of this one too. Or not.

I think losing lover and child nicely set up the possibility of a Ripley experience that was more than “Aliens Part 2.” Been there, done that, and very nicely too. And now for something completely different. “Alien 3” was surely that.

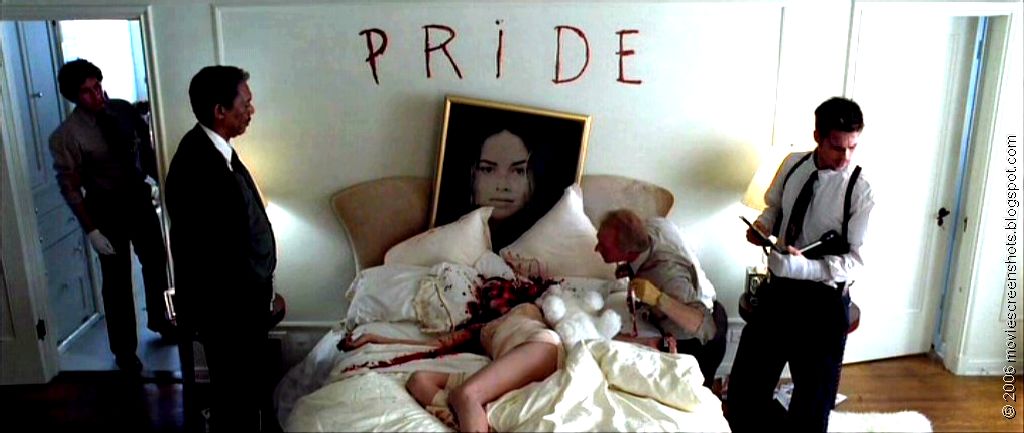

| SEVEN (or, SE7EN) (1995) In 1995 Fincher presents us with something grisly, bleak, and hard to watch. And yet . . . “Seven” in some strange way is a remarkably beautiful movie. Fincher is not the first artist to take something ugly and make a beautiful construct from it. Bruegel. Goya. Ingmar Bergman. Faulkner. You’ll think of many others. |

In the serial killer narrative the killer has a deep effect on the detective seeking him. Think of Clarice Starling in “Silence of the Lambs” and Will Graham in “Manhunter,” both movies based on excellent novels by a master of the serial killer genre. The serial killer is a brilliant manipulator, and in “Seven” that manipulation reaches some sort of apotheosis.

“Seven” is not a violent movie. Rarely is violence shown, the shock and horror coming from the aftermath of the violence committed, in both what is shown and what is talked about. When the crazy pattern comes from the Seven Deadly Sins, you can count on a lot of grisly and a lot to be talked about. The big action sequence is a chase through an apartment building mid-movie, wonderfully directed and performed, and I believe Fincher wanted to let us know that he could do that if necessary. So much of the movie involves two men talking: the older detective a week away from retirement (Morgan Freeman) and the cocky young whippersnapper brought in to work with him (Brad Pitt). Both actors do fine jobs, with their director managing to bring something fresh to a stale situation.

The look of the movie is even grimmer than the prison planet of “Alien 3.” When peeling wallpaper is shown, invariably it is the nastiest-looking peeling wallpaper ever filmed. Color is washed out, “Alien 3” being a riot of color by contrast. No sun, only rain, until the closing sequence, and there the sunlight seems wan and pale

Fincher’s 1997 offering is likely to remain for me his most problematic movie. In 1968 playwright Martin Sherman (“Bent,” “Next Year in Jerusalem”) went with Tom Miller and me to see the Howard Sackler play “The Great White Hope.” As we were leaving, Martin remarked, “I’s amazing how a play all that bad can be all that good.” I would turn his remark around for “The Game.”

Almost everything about it is excellent or beyond: direction of scenes, cinematography, editing, performance. The movie looks wonderful. But for me, the problem is the thing itself, from concept to screenplay. I simply found it totally unbelievable.

Yes, I know, on some strange level it is a comedy (the title itself might suggest that). But the best comedy itself must be believable. I believe totally in the family and the events in “A Madea Family Funeral.” I totally believe what happens to Keaton in “Seven Chances.” But what about other funny movies, say those with the Marx Brothers? Well, there the art is not in the movies but in the individual scenes, just like the dances in the Fred and Ginger movies. “The Game” aims to be a work that is a whole and believable, and to me it fails. It starts off in a most interesting fashion, gradually adding more and more layers of complication and mystery. But somewhere along the way, the shark gets jumped.

Not everyone agrees with me. The movie got some quite positive review. You might love it. Who knows?

A dark comedy about consumerism.

A horror comedy about the homosexual underpinnings of male antagonism.

An investigation of insomnia and IKEA.

A dark consideration of dependency and co-dependency.

An examination of the life not worth living.

A depiction of how a crazed charismatic leader taps into the empty lives of others to form a terrorist cult. Or a political movement.

Of course the answer is all of the above and then some, but at the time of the present writing I’d place that bottom tag at the top.

Depending on your mindset and mood, you might consider “Fight Club” to be an incredibly beautiful movie or one of the ugliest. Somehow it manages to be both. What can you expect from a movie based on a novel by Chuck Palahniuk? “The Sound of Music” this is not.

| The basic setup: Our insomniac Narrator, played by Edward Norton, frequents support groups because he finds that all the sorrowful stories and enthusiastic hugs help him sleep. The most important group is one for men who have lost their testicles to cancer. He realizes that another imposter, Marla Singer (Helena Bonham Carter in perhaps her funniest performance ever, is also crashing the groups. |

(Moment of crisis: do I go on? Will I be spoiling this movie for someone who has not seen it? Okay, crisis surmounted: either you will quit now or you have seen the movie or you have no intention ever of seeing it. I shall proceed.)

They become big buddies. Norton helps Durden snitch plastic bags filled with fats from liposuction clinics, which they use to make soap that can be sold to upscale stores. And, we learn later, that same soap product can be used to make explosives.

They are discovered punching each other in the parking lot of a bar by other men, who are quickly drawn into the excitement. A club is formed, the fight Club. There are rules: “The first rule of Fight Club is: you do not talk about Fight Club. The second rule of Fight Club is: you DO NOT talk about Fight Club!” Later on they become something of a commune in Durden’s house and gradually expand nationwide.

(This is as good a place as any to interject my belief that among other things this movie is about or at least foreshadows is the present White America First Syndrome.)

Marla calls Norton to report that she has taken an overdose of pills and wants to talk to him while she is dying. Norton couldn’t care less and leaves the phone off the hook while he goes on about his business. Durden picks up the phone, understands her plight, and goes to save her, bringing her back to the house for a lot of hot and noisy sex. Norton is upset and jealous, not of Marla but of Durden.

The group of men under thrall to Durden are instructed to commit minor and then major acts of what might, should, be labeled domestic terrorism. As matters escalate, Norton becomes disenchanted with Durden. Finding lots of boarding passes for past flights among Durden’s belongings, Norton flies in his footsteps (I like that and will let it stand) and discovers that a national network has been formed and that the people involved seem to know him but are under constraints not to so acknowledge.

And then, in a lonely hotel room, an hour and 50 minutes into the 2 hour and 20 minute movie, that Big Reveal: Norton is Durden. They are the same person. Durden conveniently appears and helps Norton (and the audience) walk through the complicated matter.

Totally unbelievable, like the setup in “The Game”? No, not for me, for within the pattern of this movie I totally believe it.

Norton tries to convince the Authorities that a major terrorist attack is underway, but the Authorities are part of the plot. He runs about the city in trench coat and underwear (long story) trying to save the world. Doesn’t work. That last loving shot has him standing with Marla (long story) high up in a skyscraper watching all the skyscrapers around them blow up and collapse: the economic structure of civilization being destroyed.

Let me reiterate: this s a comedy. Dark, violent, blood, filled with profanity, but a comedy nonetheless. Large in scope, brilliant in execution.

For the weak at heart let me stress the violence and the blood. The fights are shown in increasingly close shots, the faces in some of the latter ones looking like something that has been through a meat grinder. For those who appreciate tastefulness in their art, there is little of that here: its field of play is bad taste. Boundaries are pushed, battered even. Like those faces and bodies.

On the subject of blood, violence, and boundaries being pushed, let me jump to another director and another movie: Quentin Tarantino’s “Django Unchained,” which I first saw with a good-sized audience in Tuscaloosa with an equal split between blacks and whites. A black woman in her middle thirties and I were the last 2 people to leave the theater. I was emboldened to ask her, “What did you think?”

“I loved it,” she said. “It gave me such a rush!”

As “Flight Club” gave me.

An afterthought, several days later: Both “The Game” and “Fight Club” involve a man undergoing strange experiences ultimately to gain clarity about himself. In “The Game” he hates the experience yet embraces the self-knowledge. In “Fight Club” he embraces the experience yet is horrified by the new knowledge about himself. Both movies involve conspiracies, the former outer-directed, the latter inner-directed. The former has a warm fuzzy ending that rings totally false to me. The latter has a bleak ending that rings true.

“Panic Room” is the Fincher movie I most dreaded seeing again. I recalled my disappointment when I first saw it back in 2002. Surely this is not a Fincher movie! It seems so average! Had it been from some unknown director I might have enjoyed it more, but from Fincher? Why is he giving us a standard thriller?

Ah, those villains! Sharply detailed performances by Jared Leto, Dwight Yoakum, and particularly Forest Whitaker. Leto is wonderfully crazed and dumb, and if there is one fault in this aspect of the movie it is the idea that Whitaker could ever be taken in by this loony. Yoakum is quiet menace, until he becomes loud menace.

So, a home invasion story. I believe that in the 21st century the home invasion concept has become central to horror. This is one of the earlier examples in the century and remains one of the best. It does not carry a lot of symbolic weight here, as it does in, say, Jordan Peele’s “Us.” Even so, it has power. It is scary.

Now I can view “Panic Room” as a solid suspense thriller that gives Fincher ample opportunity to show off directorial and cinematic riffs. The opening credits are great (a Fincher trademark), showing buildings on which the artists’ names appear to be a part. The showing of the house by a real estate agent becomes an opportunity for cinematic extravagance that allows the audience to see how the house is laid out. That may be topped by the sequence in which the robbers enter, with the camera whirling ecstatically down stairwells and through bookshelves and even through the handle of a coffeepot in a bravura sequence, all the while showing their various attempts to gain access.

I have wondered if this movie was an attempt for Fincher to prove that he could be trusted with a normal and solid work with little in it of what the world (or at least I) had come to expect from Fincher. It certainly succeeds in that, and now I can see it as a brilliant exercise in style. Like so much of Hitchcock. I’m glad I have added it to my collection.

ZODIAC (2007)

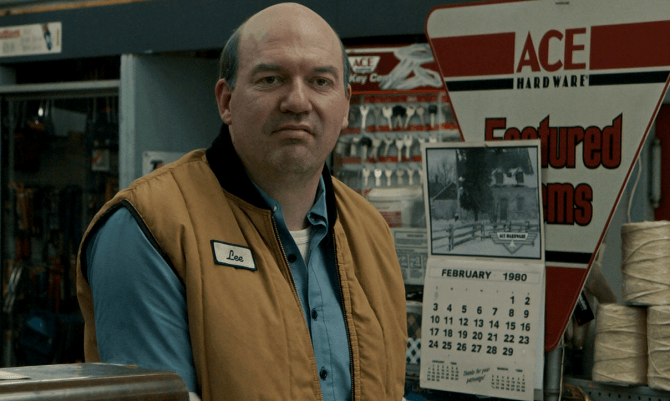

When I first saw “Zodiac” in a movie house in Tuscaloosa, my initial reaction was a vague disappointment. I had gone into it with great anticipation: Fincher tackles the serial killer genre for the second time! (Well, third, if you count the creature in “Alien 3.”) To my dismay it had none of the gothic excess of “Seven” and lacked an over-the-top villain like the one portrayed there so memorably by Keven Spacey. It lacked the neat (horrific but neat) ending of “Seven.” The killings themselves are presented in a mater-of-fact manner with little suspense. The Zodiac Killer, if he is the person hinted at in this movie, is a big lumbering blob who does not thrill: no Hannibal Lector here. The investigation itself peters out with little resolution. Mr. Fincher, where are you?

Somewhere along the way I picked up an inexpensive copy of the DVD, and as is my practice with a movie that I think I ought to have admired more than I did, waited until the spirit moved me to watch it again. This time I liked in much more. A few years later I watched it again, with even more appreciation for its worth. After my fourth viewing, for this article, I have decided that it is a brilliant movie.

The three principals in the movie are Paul Avery, police reporter for the newspaper (Robert Downey, Jr.), Dave Toschi, SF police inspector (Mark Ruffalo), and Robert Graysmith, political cartoonist for the newspaper (Jake Gyllenhaal). It is fascinating to see Downey and Ruffalo together before there confrontations as Iron Man and the Hulk. It is not polite to single out any one of three such wonderful performances, but if forced to do so I’d have to settle on Gyllenhall, but maybe that is in part because he turns out ultimately to be the centerpiece of the movie. These three are supported by an excellent cast of knowns (to name a few, Anthony Andrews, Brian Cox, Chloe Sevigny, Elias Koreas, and as the man who might be the killer or might not, John Carroll Lynch) as well as lesser-knowns and unknowns, and every performance down to the smallest walk-on in the large cast is perfection.

He is helped by the excellent screenplay by James Vanderbilt based on the 1986 book about the investigation by Robert Graysmith.

| I had not anticipated just how much I would find this movie fascinating on fourth viewing, and I wasn’t sure that I ever wanted to watch it again. I thought I’d squeezed all the juice from the orange. But now I find myself eager to watch it again for the fifth time. It grows on you. Or at least it grows on me. |

Benjamin is born November 11, 1918, a frail, wizened infant with all the physical ailments of a very old man and not expected to live. He dies in 2003, a tiny, perfect infant, but with the mental loss of someone with Alzheimer’s in his later years. During the intervening 85 years he grows up while physically aging in reverse. His death occurs in the arms of Daisy, whom he had met when he appeared to be about 80 and she was about 5, love at first sight. She has grown older while he has grown younger.

| His tale is told through a diary and other writings of Benjamin’s being read to Daisy by her daughter at her mother’s request as she lies dying, herself now old and wizened, in a New Orleans hospital during Hurricane Katrina, and through Daisy’s own remembering. “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” is not a barrel of laughs, but it is a movie filled |

This movie and its predecessor, “Zodiac,” are thus far the only 2 of Fincher’s movies set primarily in the past, although the past in “Zodiac” is much closer to the present that in “Buttons.” The approach to the past in “Zodiac” is super-realistic, rivaling “Once Upon A Time . . . in Hollywood” in picturing California in the late 1960s, although the milieus presented in the 2 movies could not be more different. In “Buttons” the physical details of the past are precise, but the directorial and cinematographic approach is much more fanciful, underscoring the fable-like quality of the story. The look, while careful, is not realistic.

The movie in its structure reminds me Shakespeare’s plays, where the fortunes of those involved rise to a climax midway through and then decline from that. Here that climax would be the period in which Benjamin and Daisy in their different paths through life manage to be about the same age and manage to fit their lives together, for a time.

Their story is, I guess you’d say, sad, but it is not that romantic sadness that enables the movie to move me to tears but the other themes. Missed opportunities. The road not taken. Carpe diem. Fate and happenstance determining our lives. Watching those we love fade away. The inevitable separation in human relationships. The aging and death that awaits us all.

| Again, performances throughout range from solid to outstanding. I’m not sure Brad Pitt will ever surpass what he does in such a subtle way as Benjamin. Of course the makeup and the technical work in pasting his face on the bodies of other actors help. I think the movie would have collapsed without Pitt. |

Kate Blanchett is wonderful as the young, older, aging, and aged Daisy. Taraji P. Henson is understated and impressive as the strong-minded black woman Queenie who runs the old folks home where the baby Benjamin is abandoned and who becomes the moth figure of his life. Mahershala Ali in his first big-screen role plays Tizzy Weathers, who works for Queenie in the kitchen and elsewhere, including her bed: I don’t have to say how good he is, for how could he not be? Jason Flemyng is Thomas Button, Benjamin’s father who first abandons what he believes is a monster and later ties to make amends. Rampai Mohadi plays Ngunda Oti, a former circus pygmy who during his time in Benjamin’s early life helps him to see that there is a big world out there to be experienced. Jared Harris is the New Orleans tugboat captain who takes on the old-looking Benjamin as a crew-member ultimately taking him as far away from New Orleans as Murmansk. There Benjamin, looking like a man in his 50s, has a love affairs with a diplomat’s wife named Elizabeth Abbott, played by the brilliant Tilda Swinton. And now let me mention someone whose performance tends to be if not overlooked at least neglected: Julia Ormond, who is wonderful as Daisy’s 40ish daughter Caroline Fuller, who discovers that Benjamin is her true father while reading the diaries to her dying mother.

There are other big names in the cast: Elle Fanning, Daisy at age 5, and Elias Koteas, so wonderful in “Zodiac,” here portraying a blind clockmaker who constructs a clock for the New Orleans train station, but one that runs backwards to the surprise of those at the dedication: he wants to turn back time so that all those who were lost in WW1 can live again. And typical in Fincher movies, every tiny part in the large cast is played to perfection. Of them all I’d have to single out for mention the elderly man in the old folks home who had been struck by lightning 7 timers and glories in describing the events.

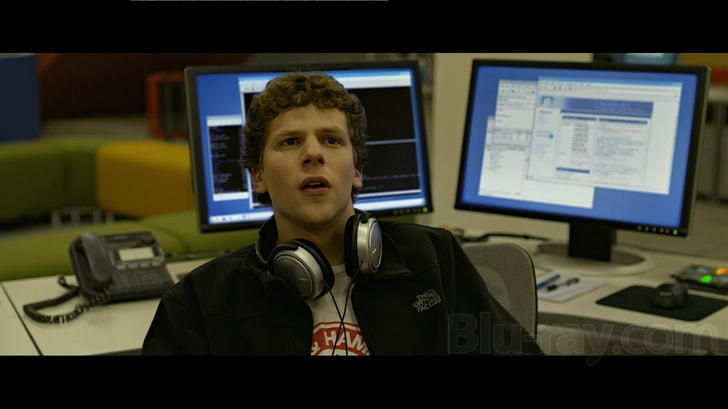

And then, after “Zodiac” and “Buttons” here comes “The Social Network.” Even without these 3, Fincher would be a major moviemaker. With them he becomes one of the most important ones of the 21st century

The biggest difference: John Foster Kane rises to the heights and falls to the depths and dies. Mark Zuckerberg rises to the heights, suffers a minor setback (although one that costs millions of dollars), and lives on, rising higher and higher.

| Question: is “Mark Zuckerberg” Mark Zuckerberg? My answer would be yes and no. I view the one in the movie as a fictional character based closely enough on the real one to justify using his real name. I view the other characters in the movie the same way. Certainty the movie does critique and analyze the real man, but (and) it is a work of art reflecting the real man. I believe the fictional |

The open scene in the movie is one of the two finest thus far in this century, the other being the long sequence that opens “Inglourious Basterds.” In both you have 2 people sitting at a table talking, in the earlier movie a German officer interviewing a man who is hiding Jews in his cellar in WW2, in the later movie a young man and young woman having a conversation that turns into an argument ending with the woman’s breaking off their relationship. In each movie the conversation sets up all that follows. In both movies the acting and the direction are breathtaking

| The open scene in the movie is one of the two finest thus far in this century, the other being the long sequence that opens “Inglourious Basterds.” In both you have 2 people sitting at a table talking, in the earlier movie a German officer interviewing a man who is hiding Jews in his cellar in WW2, in the later movie a young man and young woman |

having a conversation that turns into an argument ending with the woman’s breaking off their relationship. In each movie the conversation sets up all that follows. In both movies the acting and the direction are breathtaking.

Erica Albright, the young woman, is played by Rooney Mara. She had been working for half a decade in movies not especially memorable. Here she delivers a knockout performance with only 2 scenes, this first one, and one about mid-movie, also in a bar. Ah, the value of a great script and great direction! In a way she I the moral center of the movie. Then she gets to star in Fincher’s next.

Other young actors give standout performances: Andrew Garfield, Justin Timberlake, Max Minghella, and as the Winklevoss twins, Armie Hammer, proving early on what a great comic actor he is. Someday Fincher will be recognized for how great he is in putting together casts of wonderful actors and guiding them to wonderful performances. My DVD is accompanied by an excellent bonus disc showing Fincher working with Sorkin on details of the screenplay and directing the actors in large and small details. “Jesse, move an inch to the left” might be accompanied by an astute comment re the meaning of the scene and what the actor needs to embody.

The script is incredibly funny and filled with great lines. One of my favorite exchanges:

| Cameron Winklevoss: What, do you want to hire an IP lawyer and sue him? Divya Narendra: No, I want to hire the Sopranos to beat the shit out of him with a hammer! Tyler Winklevoss: We don't even have to do that. Cameron Winklevoss: That's right. Tyler Winklevoss: We can do that ourselves. I'm 6'5", 220, and there's two of me. |

But there is a great sadness to the movie, similar to what I find in “Zodiac” and “Button.” In “Zodiac” there is a great sadness about the inability of the workplace, newspaper and police, to satisfy the needs of those involved in the investigation. In “Benjamin Button” there is the sadness of the passing of time on love. In “Social Network” the sadness comes from the passing of friendship. Come to think of it, all of Fincher’s movies, those before these 3 and those that come after, have a deep sadness at their heart. With rue his heart is laden.

A fascinating structure: 3 nested tales. The outermost framing story: disgraced Swedish investigative reporter seeks to redeem his reputation. Inside that tale there is a second one: aging industrialist hires reporter to investigate his family and discover who among them killed his granddaughter 40 years earlier. Inside that investigation and not until almost mid-movie, the reporter discovers a horrific serial killer tale.

Brilliantly threaded through is the tale of our heroine, Lisbeth Salander, 23 years old, bisexual punk hacker, sexually abused in past and present, possibly psychotic.

Yes, there is a love affair, hot and sexy. The way that sequence is shot earned the R rating even without other aspects of the movie which would also have managed that. But Michael Blomqkvist, the reporter, is also involved in a long and loving relationship with business partner Erika Berger (Robin Wright). Erika’s husband had been able to cope with the ongoing extramarital love affair, no doubt believing that 5 or 6 nights a week with Erika was better than no nights with Erika. Michael’s wife had not been so forgiving and compromising and had divorced him.

I find it interesting that in such a long and complicated script, cut down dramatically from events in the very long novel of the same name, the Michael/Erika situation is laid out so clearly. Of course it sets up the final beat of the movie, a coda really, in which the Michael/ Lisbeth relationship is resolved. But I think it does more than that.

The movie very much concerns doubles and contrasts. Michael’s 2 relationships are vastly different. His with Erika is mature, wise, comfortable, built on understanding and compromise. His with Lisbeth is not anything like that. Both the serial killer tale and the missing Hannah tale involve doubles, deceptions, and contrasts, but they will not be revealed here.

| There is Lisbeth’s bisexuality, of course. She has 2 social workers in charge of her. The first, a kind and grandfatherly man whom she loves, suffers a devastating stroke. The next one is a heel of the worst order, who forces sex (including graphic anal rape) upon her. But have no fear: you just know that Lisbeth will get her own back, with interest. Also graphic. Yet another double and contrast in the movie. |

The movie is gorgeously photographed with exteriors in urban and rural Sweden. Acting, writing, editing, music, all superb. Does it ever rise above mere craft? Well, there is nothing mere about craft. Look at the Collected Works of Alfred Hitchcock. And I think there is at least as much meaning here as in, say, Vertigo. Fincher’s craft, his art, his imagination, and his interest in the themes I do believe lift it up. If it is not the greatest art it is at least a work by a great artist. Does it match up with his previous 3? Probably not. Does it match the previous Swedish version of the novel? Oh yes, and then some.

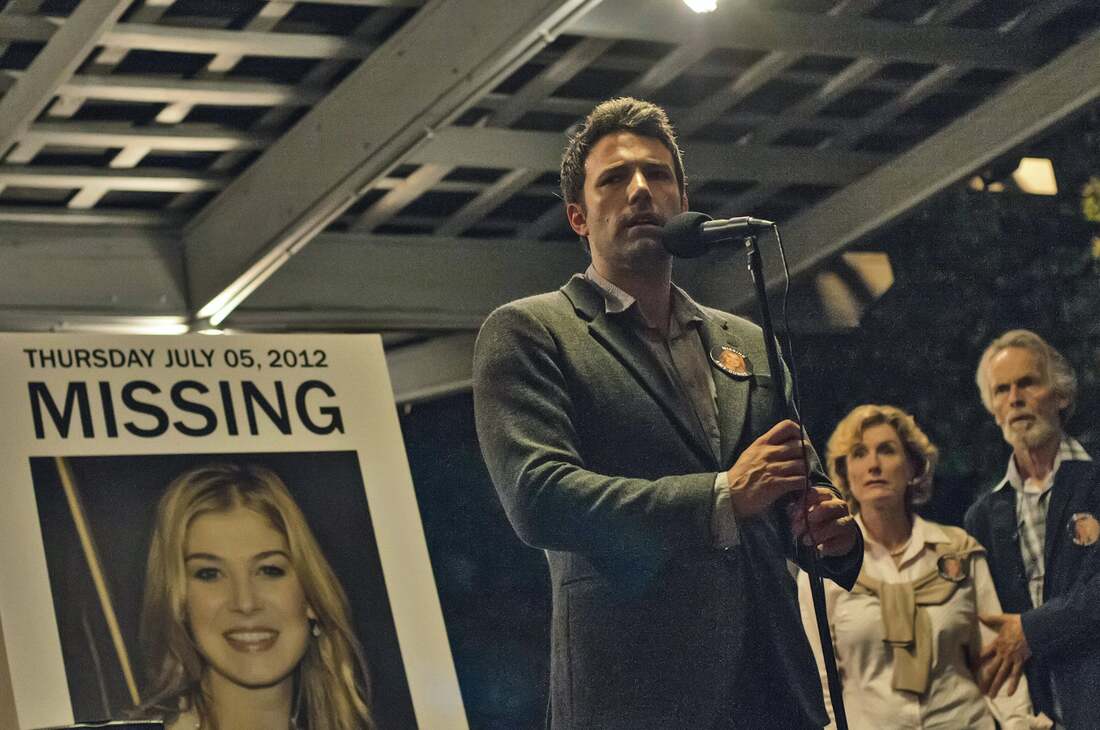

Have I seen Gone Girl 4 times now? The first time I was disappointed. Too pulpy, I thought. Not that I don’t like pulp, because I do. But from Fincher?

| The evening after I first saw it at the Hollywood 16 in Tuscaloosa I emailed my movie buddy in Los Angeles (the only actually Oscar-voter I know) the following: “Hasty initial reactions, and I reserve the right to change and modify. Excellent in all departments. Direction, acting, editing, all that stuff. But: why bother in the first place? Pretty pulpy stuff, if you ask me. Dumb jock. Crazy bitch. Who cares? (Actually, a trashier approach |

"Not a bore, and did hold my interest. Quickly I figured out that her diary/voiceover was fake. Unreliable POV sort of stuff. And when you figure out that, you sort of figure out the basic plot. I never for a moment thought Affleck was potentially a murderer.

“Not his fault, in the script. Have never read the novel (never intend to). Will probably watch it again on DVD: it may be the sort of thing that once you know what is bad about it you can enjoy more what is good about it. My sense is that it is not going to be a major Oscar contender. Maybe score and such.

“Support cast all did fine jobs, I thought. Affleck and Pike did too, to the degree that their roles (which were basically plot constructs) let them.”

I’m glad I put that reservation in the first sentence. I have changed my mind. Every time I watch it I like it more. Pulpy? I’ll stand by that adjective. But then most of Hitchcock is pulpy, and that doesn’t get too much in the way of our appreciating him. And for me, this is the most Hitchcockian movie that Fincher has made. Hitchcock would have loved this material. Plus it has a blond.

I stand by my remark that once you realize there is an unreliable narrator you figure out the plot. And if by unreliable narrator you mean a person who lies, there is more than one in the movie. But repeated viewings have shown me that there is more to the movie than plot.

| I most regret my slighting of the performances of Rosamund Pike and Ben Affleck. Pike has never been better, and her performance is masterful. I find myself amazed now at how her performance always fits perfectly the particular requirements of the construct, whether it be in her portrayal of herself as how she presents in the diary, how she is perceived by her husband. |

In a much earlier piece I wrote after my first viewing I wondered if the movie might have been better than Gillian Flynn not adapted her own novel. I’ve changed my mind about that. Her script is fine, possibly more than that. Having recently watched a piece showing in great detail how Fincher and his screenwriter Aaron Sorkin batted about details and lines from the script of The Social Network, I have decided that likely he and Flynn also did so on Gone Girl.

I have always thought that script is as much about structure as it is about words spoken. In Gone Girl it is amazing how after the pileup of complications in the first hour everything has been presented so clearly and memorably that now in seconds all of that material can be explained in a different and immediately comprehensible way.

Now that on subsequent viewings I had accepted and digested the pulp, what else do I see to chew on?

Coasts vs. fly-over. She from New York, he from Missouri.

Class: hers vs. his.

Wealth and the lack thereof: again, hers vs. his. And then, her wealth also is lost.

Man vs. woman. Fincher here and elsewhere seems to believe that seldom can the twain meet comfortably. He also sees how the inherent problems are execrated by the economic downturn.

Media manipulation and manipulation of the media.

Freedom vs. control.

Surface and what lies beneath.

All that and more.

I am sorry that people hold it against this movie that the Woman is not a good role model. (Well, neither is the Man, if you ask me.) I’m not sure that Hamlet and Lear and Othello and Oberon and Lady Macbeth and Cleopatra and Titania and any number of others I could name are good role models either. That does not keep them from being persons of interest worthy of our attention. Most certainly the Dunnes, Nick and Amy, are persons not to be emulated. I suspect they are not as great as creations as those persons from Shakespeare, but don’t discard them because they’re not nice or likeable or positive examples of something or other.

The ending of the movie is incredibly dark, growing darker every time I watch it. And it is perfect. And our central couple end up getting just what they deserve.

UP NEXT?

Manx. Announced in pre-production for 2020 release, it follows screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz's tumultuous development of Orson Welles's movie Citizen Kane, starring Gary Oldman with screenplay by Jack Fincher, the director’s father. No way would I consider missing it.

World War Z 2. Co-produced by and starring Brad Pitt, who starred in the first one. I’ll be there, if I’m still alive and functioning.

Yes, I know Fincher has done a lot of television work lately, some of it considered notable. Since I don’t know that work personally, I’ll skip any commentary, other than to say I hope he gets back more into movies. It has been 5 years since Gone Girl, and I miss him in my life.

AFTERTHOUGTHS

Sometimes in can be dangerous to take a long trip with a friend, whether it be an ocean cruise or a driving trip through the United States. It is hard to tell in advance what the journey will do to the friendship. Such thoughts entered my mind as I embarked on my big summer retrospective project of re-watching all of the movies of David Fincher. Would I become bored with his company as we moved along? What would I think of him once I got through?

I didn’t rush. I averaged perhaps one a week, and I would think about each one and write about it before moving on to the next. Instead of becoming bored, I became more and more fascinated by his work, and now that the viewing part of the project has been completed I find myself with an even deeper appreciation, understanding, and love for what he has thus far produced.

Brad Pitt has now appeared in 3 of Fincher’s 10 movies and is set for “Manx,” their 4th collaboration. He has been great in each one of them, providing his director and us with totally different performances. Can we call him Fincher’s muse, as, say, we do with Robert DeNiro and Martin Scorsese? The only nomination for the Oscar for Best Actor for his work with Fincher was for his portrayal of Benjamin Button. He lost. He has never won an Oscar for his acting.

Fincher himself has been nominated only twice for his direction, “The Social Network” and “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.” He lost both times.

A thought: they are both too good for the Oscars. Fincher may well be like Stanley Kubrick, who never won an Oscar for directing several of the finest movies of all time. Kubrick’s work has stood the test of time, overshadowing those who did win Oscars for the years in which his work appeared. I think Fincher may well be joined in this category by the other 3 directors who, along with Fincher, I think are our greatest directors working today. Terence Davies, Terrence Malick, and Christopher Nolan. And they too may get their own retrospectives and essays over time.

Something else my 4 living directors have in common with the late Kubrick is thee great number of fine performances in their work ignored by the Oscars. Something that I sort of recalled but had impressed firmly in my mind during my Fincher retrospective was the quality of performance throughout his work. He is wonderful with actors.

In the sheer craft and technique of movie-making Fincher ranks with the greatest. He is as careful with that as he is with performance. The look of each movie is different from all of the others, but the look of each immediately announces that this is a David Fincher movie. As does his use of music, another matter deserving of the deepest consideration.

I have tucked away my Fincher movies for the present, but already I am anticipating my subsequent viewings. And you know what? I’ll bet I will like, love, them even more.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed