“ON THE WHOLE I’D RATHER BE IN PHILADELPHIA”

In retrospect you look back and wonder how you could have allowed yourself to be so demeaned. Not that I felt demeaned at the time. I felt richly rewarded, even privileged, to be in the vortex of such horseshit. Now as I look back, I find myself plunged into the immediacy of the moment. It is as fresh now as it is then. And the whole thing is a hoot.

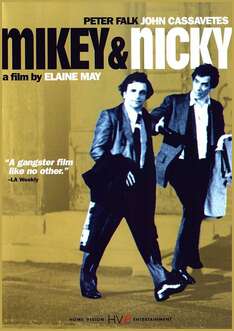

I’m the unit publicist on Mikey and Nicky and its director, Elaine May, is not supposed to know I exist. I’m not to go near the set. She is not to lay eyes on me. If she did, I’m told, she would freak out. Sounds remarkably like the basis for a Nichols and May comedy sketch.

What kind of job is this, to go to Philadelphia on a movie location and be told you are to stay in your hotel room? Hey, it’s okay, right? Cushy job. Paid vacation. I have the new Ross MacDonald novel, Sleeping Beauty, and when I’m through with that I’ve got E. M. Forster’s Howard’s End, which I’ve always wanted to read. I’ve got a TV and the Watergate hearings are on. More than enough to entertain me.

But it is not. The more I think about it, the more pissed I get. The real entertainment is out there, where I’m supposed to be working. I’m being paid to watch Elaine May, Peter Falk, and John Cassavetes make a movie. Somehow I’ve got to get in there and watch it.

Now this is the summer of 1973. If you know your Watergate you’ve probably already figured out that date. Paramount’s big publicity guns are trained on The Great Gatsby shooting in Newport. Socialite extras, twenties fashions, Stutz Bearcats, and all that. And Robert Redford in the title role of Jay Gatsby. Glamour! Lights! Media! Elaine May, on the other hand, doesn’t want so much as a cap pistol pointed at Mikey and Nicky.

One week before principal photography is to begin, before the cast and crew assemble at their Philadelphia location and the cameras start rolling, Elaine’s novice producer Michael Hausman remains adamant about not wanting a unit publicist on the picture.

For one thing, he’s trying to palm it off as an independent production, trying to hide the fact that it is bankrolled by Paramount and is already on Paramount’s release schedule. He’ll get union concessions this way, or possibly he can bypass the union entirely. By union, I mean Teamsters. Even though the rest of the crew is union, he doesn’t want Teamsters. He doesn’t envision any need for them. To use Teamsters would inflate the budget considerably. My presence would bring on the Teamsters, he’s afraid. I’d be plastering the name “Paramount” all over the trades. In every press release and column item.

I am anathema. Cries of “Leper!” will be heard all over the city when I arrive to claim my position as the film’s unit publicist.

Gordon Weaver is Paramount’s director of publicity, and, bless him, he’s determined that I shall go to Philadelphia. Talking soft and silky and rationally, he convinces Mike Hausman that it is essential to have a PR guy around, at least for the first three or four weeks, if for no other reason than to gather production and program notes for use as a press kit when the picture is released. And the presence of a movie company and bona fide movie stars in Philadelphia is obviously going to excite a hell of a lot of hoopla. Somebody will have to handle the hoops. Is Hausman prepared to? Of course not. Nobody seems to know what a unit publicist does until he or she needs someone to do what a unit publicist does. We get no respect. Low man on a very tall totem pole. (Although we’re looked on sometimes with envy too, don’t you think, seeming to do nothing and hobnobbing off-camera with stars and sitting in director chairs and being allowed other tokens of privilege.)

Entertainment editors. Reporters. Columnists. Journalistic would-be starfuckers. (If that isn’t one word, it ought to be.) Hey, Hausman, won’t they all wish to take note of the fact that Columbo, the incredibly popular TV detective of the baggy trench coat, Peter Falk himself, will be working in their city for the entire summer, along with his actor/director buddy and frequent collaborator, John Cassavetes?

Have you any concept, Michael Hausman, any idea, of the barrage of phone calls the production office will be getting? Who will take these calls? Who will meet with those clamoring for access to Falk and Cassavetes, be the intermediary in granting or denying access as well as scheduling and presiding over interviews? You, Mike? Elaine May will be directing her third picture in the city of her birth. A story there. The film will be shot exclusively in Philadelphia and exclusively at night. A story. The unit publicist must gather all this information for future if not present use. Not to mention the Philadelphia press who will want to know and deserve to know details about the film’s production. The company will have a public relations problem if these concerns are not addressed promptly and politely. Will Hausman have the time and inclination to deal with them?

Mike got the point. “Send me somebody,” he said. I was the one Gordon would send. Gordon called me to his office overlooking Central Park in the Gulf and Western Building on Columbus Circle, and we spoke to Mike by telephone. Mike had caveats and conditions, and almost the first thing he said to me was, “Elaine mustn’t know.”

“Mustn’t know what?” I wanted to know.

“That you’re in town. Who you are,” Mike said.

“You must be kidding.”

“I’m serious.”

“But she’ll see me.”

“Where?”

“On the set.”

“You won’t be on the set.”

“If I’m not on set, where will I be?”

“In your room, writing.”

“What am I going to write?”

“Make it up.”

Gordon laughed. Mike laughed. All three of us, long distance laughing. All of us recognizing that it was loony bin time.

Make it up. It was a refrain I was to hear often during the next three weeks, especially from Peter Falk. If his director was mad, he harbored an even wilder madness of his own.

“Believe me, Tom, trust me. I know Elaine,” said Mike. He’d been her production manager on The Heartbreak Kid.

“With Elaine you have to insinuate yourself. She likes familiar faces. What she doesn’t like are strange faces that turn out to be publicity faces. Maybe we’ll let her see your face gradually, maybe the second week, maybe she’ll accept it. But please God she never finds out you’re a publicist sent by Paramount. She’ll think you’re here to spy on her.”

I sneaked into the City of Brotherly Love on the rainy Sunday night of May 20 before the picture was to start shooting the evening of the following day. To add to the welcome, or lack of it, I arrived in the middle of both a thunderstorm and a taxi strike. Five of us and our wet umbrellas were crowded into a private automobile, one of many pressed into service for the emergency. Like an airport van, it made all the hotel stops. Mine was the Warwick. “It’s where the stars stay,” someone said. The movie company was staying there, and the production office was on the top floor in the penthouse suite.

My room was nice enough, but I was disappointed that it contained two double beds which took up most of the space. Also there was no refrigerator, no hotplate, no kitchen nook. The refrigerator I would most acutely miss. I had forgotten to specify it when I made my deal. I would never forget it again. The bathroom was a charmer, old little squared white tile and massive porcelain bathtub and sink. It was nine-thirty in the evening. I called the production office. Surely somebody would be there the night before principal photography was to begin.

Somebody was. The voice sounded like Elaine May’s. I had come a cropper. I had to report to somebody that I was here, didn’t I? But what if this was Elaine? What would I do then?

Her name was Nola, she said, “Assistant to the Director.” Nola Safro, and that is indeed how she was listed on the crew sheet I would later receive. A name like that deserves an actress behind it. Especially with that voice.

“And who did you say you are?”

I told her, but didn’t say I was the unit publicist. I still wasn’t sure but what I had Elaine on the line. Traps, I feared, were everywhere. All too cloak and dagger.

Her voice lowered an octave. She whispered into the phone, “Oh yes, Mike told me about you. Come up tomorrow morning.”

I asked her if there was a bar in the hotel where I could get a drink and a snack.

“It’s closed on Sunday,” she said. She mentioned a bar about a block away.

Even through it was still pouring, I went there. Not much in the way of food, but everything else was choice. A gay bar. Interesting that Nola Safro should have sent me there. I didn’t even know the lady, and here she was, my Good Samaritan.

I met Nola Safro the next day and still wasn’t certain that she wasn’t Elaine May. I’d met Elaine some years before at a Bring Your Own Bottle party at Ben Bagley’s. She was with lyricist Sheldon Harnick to whom she was later, if briefly, married. I’d seen her in performance with Mike Nichols both in cabaret and on Broadway. I felt sure I would know her if I saw her. I eyed Nora Safro very carefully.

She was rubbing lotion into her skin and complaining about dishwater hands. She had just come from Elaine May’s suite where Elaine, on this first day of shooting of her new film, was hard at work scouring her dressing room table with a very soapy and wet steel wool scouring pad. So much, in Elaine’s opinion, for the Warwick staff.

Nola introduced me to three other women working in the office: Shelly, Jackie, and Pat. Jackie turned out to be Elaine’s cousin and became a major source of information. Pat, the office manager, was involved romantically with (perhaps married to) Mike Hausman. The office manager designation was her own idea. In another company she would likely have been called the production secretary.

I was delighted when familiar and friendly faces began to turn up, crew members I’d worked with on other films. Bob Visciglia, the prop man, I had worked with on Alex in Wonderland, and Randy Munkacsi, the stills photographer, on Shaft.

Bob Visciglia was trying not to worry. He had just reviewed the extended shooting schedule of Elaine’s two previous films. Such a schedule overrun for Mikey and Nicky might mean the loss of another job he had lined up.

He tried to look at it optimistically. “They’ve got Falk only for the summer, right? So how can they not finish on time?”

Had I been endowed with prescience, I might have replied, “Let me count the ways!”

I was handed a cast and crew list that gave their room numbers at the Warwick. It surprised me to see that I was on it, room 937, and that it succinctly and without equivocation gave my crew position as that of publicist.

Now who was kidding whom? Elaine May wouldn’t see this list? Why the subterfuge?

Elaine was in 1108, Cassavetes in 808, Falk in 1008. The 08 series seemed to be choice. And I ended up in the 37 line with no refrigerator.

Shelley offered me a granola cookie. She gave me a list of nearby health food stores that I might like to try if I were “into that kind of thing.”

Shelley’s two cats were in residence in the office, one of them embarrassingly in heat. I patted it and tried to focus its attention elsewhere.

Putting down one phone and in the process of picking up another, Mike Hausman greeted me and said he would drive me that afternoon to the night’s location and give me a tour. I scrounged from him a list of locations (guarded zealously by Pat) despite his misgivings about allowing me to see it. Did he think the list would be published the next day in a bordered box on the front page of the Inquirer? I assured him I would not deal in location specifics when speaking with the press.

The production office staff was housed in the larger of two living rooms in the penthouse suite, which you had to pass through to get to Mike’s office in the smaller room. One of the bedrooms was the company’s editing room where film editor John Carter (not on Mars but sometimes I pictured him as wishing he were) would work with two assistants on state-of-the-art editing machines and Movieolas. The room would be used for a brief while for storage of exposed film, but the cans of film would quickly proliferate in seemingly autonomous self-duplication like the bass fiddle in a W. C. Fields two-reel comedy. More space would have to be found. Another bedroom, the office of the location auditor, would become a much-frequented and much-argued-in room.

Until a typewriter could be arranged for me, Pat let me borrow one of the office machines.

Mike Hausman became greatly concerned when he learned what I immediately would be up to: composing and transmitting to both the Hollywood Reporter and Daily Variety in Los Angeles a key cast and crew list for publication in the current Production Chart listings of each of the periodicals. The listings are by studio, and if a film has no studio affiliation it is listed as an independent. Mike did not want Mikey and Nicky listed as a Paramount Picture but instead placed with the independents with “Mikey and Nicky Productions, Inc.” as the identified producing organization. Toward the end of production he would allow it to be announced that the film was a Paramount pick-up, one that Paramount had bought in on after the fact rather than before.

But it was not to be.

Before I was hired, the Paramount publicity department had already distributed press releases announcing its participation in the project, and the film’s title had appeared in the press as a Paramount release. I had to follow Paramount’s lead in this decision and not Hausman’s.

Mike was not happy. More than ever he feared that stressing Paramount’s proprietary interest would up the ante with the various unions with whom he had to deal. He was still trying to keep the lid on that somewhat agitated Pandora’s Box.

It took three days to resolve this situation, three days during which I was to refrain from direct communication with the Reporter and Variety. While it wasn’t an easy time, I became grateful for the respite; for during that period the original director of photography was replaced or had resigned, and the first assistant cameraman (the focus cameraman) departed shortly thereafter. Some claimed for the latter an incipient nervous breakdown.

Production Chart listings in 1973 usually cited eight members of a film’s personnel: producer, director, author of the screenplay, director of photography, film editor, art director, sound man, possibly the production manager (Mike Hausman was serving in this capacity as well as producer), often the first assistant director, and, at least in the Hollywood Reporter, the unit publicist. Directly under the film’s title, in smaller print, came the names of actors thus far cast.

Our credits were few, and two of them were Elaine May’s as director and scenarist. She also had penciled herself in to play a featured role but didn’t want that fact revealed. The other listings were the two for Hausman, Vic Kemper as director of photography, editor John Carter, assistant director Pete Scoppa, and me. Hausman told me to keep it trim. Ordinarily Anthea Sylbert as art director would have been listed, but she was by union affiliation a costume designer and had not yet ironed out several union wrinkles that would allow her to surface safely in her new designation.

Other films listed under Paramount’s banner that first week of June 1973 were The Little Prince, Ash Wednesday, The Parallax View, The White Dawn, and Zeffirelli’s Camille, a film shortly to be aborted. The Great Gatsby, not due to begin shooting until June 11, was not yet listed.

Mike elaborated a bit more on why he wished to keep the company free of Teamster drivers. The rap on Teamster drivers is that they drive and nothing more. Often they drive to a location chauffeuring an actor or delivering material and then remain there on call, perhaps until the end of the day’s shoot, free until then to play cards, shoot the breeze, snooze, or whatever. Their inert presence and high visibility being so can be demoralizing to a highly active, harried, high-voltage crew.

The company would be working in a close radius from the Warwick. The small amount of driving to be done could be handled by Hausman’s unit manager John Starke or a couple of production assistants or even Hausman himself. The fewer the better.

Ultimately Hausman’s concern was budgetary. It was very important to him that he hold costs down. Paramount’s then president Frank Yablans had already been contacted by the Teamsters union with a complaint about the lack of union drivers. Yablans had instructed Hausman to put two Teamster drivers on salary with the promise that the salaries would not be charged against Hausman’s budget.

I was typing advance production notes in my room that first morning when the phone rang. Nola. Could I please hurry back to the production office? A reporter from the Philadelphia Bulletin had turned up with his editor’s instruction not to come back until he had a story on the film.

Luckily, I had on my own time and without recompense researched the director and stars the previous week in New York (this, my usual habit and preference, tended to save a lot of time and heartache later on). I had read Elaine’s script and had seen the film’s location schedule. I felt prepared to talk about the film in general terms.

When I walked into the office, Joe Adcock, the reporter, was asking questions and taking notes about the office cats. Shelly was amused that Adcock’s demanded story should have reduced him to such a task. There was also a flurry of concern among the staff, passed on to me later, as to how Adcock might use the cats metaphorically.

The paranoid mind boggles.

To escape the confusion and distraction of the cats, I suggested to Adcock that we go to the Warwick lobby for a chat.

He asked, “Is the title Mikey and Nicky perhaps a play on Mike Nichols?” I loved the connection and wished I had thought of it. I told him that I didn’t know, but by all means use it. (In the story published the following day in the Bulletin he did use it, and I was quoted profusely and authoritatively.)

“What is the film about?” Adcock asked.

“Next train out, guy,” I could hear Hausman’s voice whispering in my inner ear by way of warning.

With some trepidation I summarized Elaine’s story and theme. In ideal circumstances I would have been allowed to confer with the director or producer before becoming a spokesman. I was in dangerous territory, winging it like this.

“It’s about a man in the organization . . .” I began. I was treading barefoot on shards of glass. Through experience, I knew enough to eschew the inflammatory word Mafia, either specifically or generically. On two films, Shaft and The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, protestations in the form of threats had caused me to mitigate terminology. “A man in an organization who thinks there’s a contract on him but he’s not sure and he can’t figure out who. . .”

I resented not having been prepped. I had no idea the tone Elaine intended to take in filming her screenplay. I thought it was a comedy.

Jackie had said, “Oh, no, she’s going to be deadly serious with this. Don’t ever dare say it’s a comedy.”

“But I laughed out loud when I read it.”

“I did too, but don’t let anybody else hear you say it.”

After Adcock left with something resembling a story, I realized I had to do repair work with Philadelphia’s other two newspapers. I couldn’t have it appear that we were favoring the Bulletin. I called the entertainment editor/movie critic of the Inquirer and gave her a variant of the rundown that Adcock had received. I stopped just short of telling her about the office cats. Adcock mentioned the cats but used them circumspectly as office color. The staff was relieved.

The Inquirer story was accompanied by a morgue photo of Elaine that made her look like an ingénue. The Bulletin ran an uncharacteristic photo of our director, widely grinning, looking as hair-sprayed and bouffant as any 1950s West Texas debutante. “Where did they get that picture,” Shelly gasped. The News merely carried column items. It was agreed on penalty of death that no one would show Elaine any clippings. She wasn’t likely to come across the stories on her own. “She never looks at a paper,” Jackie said.

Both the Inquirer and the Bulletin gave the name of what would be our location for the first three weeks of shooting, but no harm done. It was all interior and all at night. It was the abandoned Essex Hotel at Thirteenth and Filbert Streets, about a block and a half from Philadelphia’s instantly recognizable landmark city hall. In Mikey and Nicky it would be called the Royale Hotel. The Essex had been closed for seven years, since October 1966.

Hausman drove me to the Essex early the first night of shooting, about five o’clock. Elaine wouldn’t be there for a couple of hours yet. Peter Falk was already there. Mike introduced me to him on the run. I sat with Falk in a red cracked-leather booth in what had been the hotel restaurant while Mike went to see about things on the second floor where crew were setting up for the shooting of John Cassavetes’s opening scene, the first scene of the film.

Peter Falk would not be needed for hours. He was early because he would rather be where the action was than hanging about his hotel room waiting for his call. He was playing aimlessly with a deck of cards. He looked at me as if I were lying when I told him I was the publicist. It made sense to him when I told him that Elaine didn’t know I was there and as far as Mike Hausman was concerned would never know.

Falk grinned. “I won’t say anything.”

He wanted to show me something. We walked around what was left of the restaurant and its kitchen.

“It looks like it was walked out of like on the last day of the world, right? Look at it—menus. Two of them here open where somebody left them, like they just ordered, or maybe not even ordered yet. Look at the water glasses. The inner rings. Lower and lower on the glass as the water evaporated. And look over here. Crumpled napkins on the tables . . .” There were three tables still with used napkins on them. “There were even dirty dishes, they tell me. They cleared out some of this crap before we moved in. The prop guys. But go in there in the kitchen and look around.”

He followed me in.

“Pots and pans. All this heavy artillery hanging from the ceiling. Like bats. Did you ever see so many cobwebs? Is that bat or rat shit on the floor? Is that like dirt you’ve ever seen before? And have you looked in any of the rooms upstairs?”

“I’m not allowed in any of the rooms upstairs.”

Falk chuckled. “Elaine’s not here yet. Come take a look. I’ll be with you. Nobody’s going to eat you.”

We left the kitchen and returned to the restaurant and walked past what had been the cashier’s desk where an old dusty cash register was still stationed, its empty money drawer hanging open.

“Funny how they can do that. Just walk out and leave a place. Even Cokes in the Coke machine. Just walk out and leave everything and put a padlock on the door.”

Like Columbo, he tried to puzzle it out.

“What did they do, suddenly go bankrupt? Were they evicted? Some terrible plague?”

I hoped one day to uncover the mystery of the Essex Hotel. I fancy that Columbo and I working as a team might have been able to. We never got the chance.

Falk took me to the upstairs shooting area. With all the two-by-fours being slung about and hazardous objects and workers’ tools at every turn, with every inch of space crowded with a crew unhappy with your usurping any more of their space, we didn’t stay long. I appreciated the tour but didn’t find it particularly rewarding. The walls were solid. The rooms were small. How much better it would have been, I thought, to have removable walls, expandable space. I wondered what could be achieved shooting in this dump that couldn’t have been achieved so much easier in the comfort of a studio.

Joe Adcock’s story in the Bulletin the next day would feature the Essex prominently. He managed to interview carpenters and other members of the crew. He found David Moon, the scenic artist, smearing Vaseline on a wall before covering it with plaster. “That way the plaster will chip off easily and give us that seedy hotel look.” Giving the Essex a seedy hotel look was like adding fuzz to a caterpillar. Anthea Sylbert had spent her day exchanging a bathroom with a closet and moving the door of Nicky’s (Cassavetes) room a few inches so that a clean line of corridor would be visible when the door opened.

It was inevitable that Mike Hausman would see me. I was braced for it. Seeing that I was with Falk, he didn’t say anything. His grin said it all. When it was nearing time for Elaine to arrive, he instructed a production assistant to drive me back to the hotel.

There were plans for Mayor Frank Rizzo to visit the Essex Hotel on Wednesday evening about five o’clock, just before shooting started. Elaine May, Falk, and Cassavetes would act as guides showing the mayor and his aides through the rubble that was our location. Newsprint and broadcast media were invited.

If the media were invited, surely it followed that I, the company’s resident public relations person, would also be there, perhaps—dare I hope?—even participate in the event. No longer the leper on the ninth floor.

“I don’t follow your reasoning,” Mike said when I broached the subject.

“Hey, Mike, I’m the publicist, remember? I deal with the media.”

“Uh uh, not on this occasion. Betty Croll will deal with the media.”

Betty Croll of city representative Henry Bollinger’s office had found the hotel and other locations for the company. The mayor’s visit would be a hug-fest of a photo opportunity for Mayor Rizzo and Peter Falk and payback to Croll.

“And what am I going to be doing?” I asked.

“Oh, you can be there, I guess. We’ll pretend you’re a reporter. I’ve got it all figured. We like you, Tom, we’re glad you’re here.”

I felt the sentiment was sincere and the sarcasm only a tart twist of lemon for flavor. I said, “As long as I’m posing as a reporter, I think I’ll pose a few questions for Elaine.” Mike’s look told me I was kidding.

The visitation scheduled for Wednesday did not take place but was rescheduled for the following Tuesday, this time at the mayor’s office. Instead of Mayor Rizzo coming to us, we had to go to him. It was labeled a courtesy call on the mayor by May, Falk, and Cassavetes.

The morning after the first night of shooting, I was in the hotel lobby at eight on my way to breakfast. I met the crew coming in from the night’s work. I ducked behind a pillar and a potted palm in hopes of getting a glimpse of Elaine. Not to be. I wouldn’t get to see her until the press conference in the mayor’s office.

But at least I tried.

I pulled the unpardonable on the third night of shooting and showed up on my own at the Essex. Elaine and other key personnel were on the second floor shooting. I could see no harm or threat so long as I stayed on the ground floor. I sat in one of the restaurant booths and had coffee with Jackie in the middle of all the rubble. Mike spotted me. Despite his beard that could have blithely been swiped from a Smith Brothers cough drop box, I’m convinced I saw him blanch.

“What are you doing here?”

“Well, I . . .”

“Come on.”

He led me outside to the car, politely but pointedly held the door open for me, and drove me personally back to the hotel. He let me out. “Go to bed.” He said it gently, apologetically, and humorously. Then he drove off.

I didn’t go to bed. I went to a bar.

Let me pause a moment for Jackie Peters, the production assistant and crew feeder. It didn’t take long for me to realize that she and the ubiquitous Nola were the real line of communication, tenuous and surreptitious as it might be, to Elaine May. Each of them could pop into May’s eleventh floor suite at will. Jackie was definitely someone to cultivate. And besides, she was nice.

After Joe Adcock had come up with the idea of the film’s title being a play on the name Mike Nichols and since he had already used it in the Bulletin, I had the bright idea of recycling it as a news item for the trades or perhaps the New York Daily News, either as conjecture or as something commented on by Elaine.

I asked Jackie to query Elaine about it. Jackie left the office, went down to Elaine’s suite, soon returned, frowning. “Elaine wants to know, has that been used?”

“No,” I said.

Jackie was relieved. “Elaine says not to use it.”

“But it’s already been used.”

Jackie said severely, “You just said it hadn’t.”

“I mean, not by me. It’s not mine. It’s Joe Adcock’s. It’s in his story today in the Bulletin.” Didn’t anybody take a look at the story, I wondered.

Jackie was horrified. “Oh, my God!”

“I just wanted to give it to somebody else. I thought Elaine might get a kick out of it or something, maybe comment on it.”

Jackie shook her head. “Forget it. Let’s just hope she doesn’t see the story. I don’t think she will.”

“Did you tell her who I was?” I asked.

“What do you mean?”

“Elaine. When you asked her about the item. Who did you say wanted to know?”

“Oh, just some guy in the office,” said Jackie.

“You didn’t say the publicist?”

She looked at me pityingly. “Are you kidding?”

Jackie resembled a ripe and unpolished Rita Hayworth. She had been a cabaret singer and had appeared in one or two movies. She was now in charge of feeding a crew on location. On that first day of production she didn’t have a clue where to start. She was blithely winging it. She hadn’t yet firmed up the night’s menu, the mode of delivery, or even the supplier. She wasn’t particularly worried. She was making phone calls, stating her problem, taking bids. She stuck her hand over the receiver to ask, “Do you think they’d like ham sandwiches?”

My startled expression was her answer. She wrinkled her nose, considered a moment, then told the man on the phone she’d get back to him.

“If worse comes to worse, we can always call McDonald’s,” she said.

“At midnight?” I didn’t think so.

If I were Jackie I would be worried. The crew, to be fed at two in the morning, would expect hot food, ample in quantity, and exemplary in quality. There would be a lot of bitching if it wasn’t.

It was when I was having coffee with her in the booth at the Essex that I had learned that she was Elaine’s cousin, their mothers being sisters. She and Elaine were the same age. From about the time they were nine, they grew up together after their fathers, independent of one another, were killed in automobile accidents. Their mothers converged on Chicago with their daughters to live with a brother, Elaine’s and Jackie’s uncle, who managed a nightclub. The germ of Mikey and Nicky originated in this uncle’s story, Jackie hinted, something that had happened in the early stages of the Second World War or just previous to it. After three years in Chicago, the whole family including the uncle moved to Los Angeles where the girls attended junior high school and Fairfax High. Elaine Berlin, as she was then, didn’t stay at Fairfax long. While a student there, she met and married upperclassman Marvin May. Elaine was sixteen at the time. Jackie, Elaine, and their menfolk would double date in a coupe with a rumble seat, and they would flip to see which couple got the choice rumble seat. Elaine and Marvin usually won. The birth of a daughter (Jeannie Berlin) put an end to Elaine’s rumble seat days as well as to her formal education, although she had a long history of being a notorious truant. Elaine parked her child with her mother and enrolled for acting lessons with Stanislavsky-trained actress Maria Ouspenskaya, a Hollywood character actress mainstay from the mid-thirties until her death in 1949. When Elaine’s marriage to Marvin broke up after two years, she left Jeannie in her mother’s custody and returned to Chicago, where she sat in on whatever classes appealed to her and attended whatever extracurricular events she chose at the university (although she never officially enrolled). It was a course that eventually and happily led to Mike Nichols.

And fame.

Which brings us back to Mayor Michael Rizzo.

Mike Hausman told me to be in the lobby of the Warwick at three forty-five and he’d have a ride for me. When I got to the lobby, Peter Falk, John Cassavetes, and Gena Rolands, Cassavetes’s wife and frequent leading lady in films he directed, were already there.

Falk introduced me. Cassavetes was surprised to learn that a publicist was on the picture. “How come I haven’t seen you around?”

Between us, Falk and I told him how come. Cassavetes snickered. Gena Rolands smiled at me sympathetically and shook her head to convey understanding. She was visiting from Los Angeles, she said, and would be in Philadelphia only a few days.

Mike Hausman and his unit manager John Starke joined us in the lobby. Mike hustled me out of the hotel and had Starke take me on to City Hall. Mike said he would bring the others.

John Starke circled City Hall before we found a parking place. We waited for the party in the other car to arrive. When they didn’t show up after about five minutes, we wondered if perhaps they had managed to get there before we did. We went on up to the floor where the mayor’s office was located. A City Hall aide came running and asked frantically, “Where are they? It’s four-fourteen!”

Neither John nor I was surprised. He had waited in enough automobiles and beside enough elevators to know that you do not get Elaine May anywhere on time. He told me that once he had waited for her in his car for thirty minutes in front of the Warwick to take her to location. She finally emerged breathlessly to admonish him, “You must learn to be on time, John. We’re on a budget, you know, and time is money.”

The corridor outside the mayor’s office was jammed with reporters and camera crews and with what looked like half of the city’s civil servants, at least those who worked at City Hall, all of them Columbo fans.

I mumbled excuses for the tardy arrival of our stars. As hostility built, directed at us, of course, since the stars were nowhere in sight, John suggested urgently to me that we get the hell out of there.

Just as we were beating our hasty retreat, the elevator doors opened and out stepped, voila!--The Stars! There was pandemonium, everybody jockeying for position or for whatever they could get of Peter Falk: a touch, a feel, a look, a picture. Maybe even a piece. He was pushed, the rest of us pushed along with him, by the sheer momentum of the crowd, toward the mayor’s office. A buxom blonde of uncertain years threw her arms around him. Ordinarily the publicist would have been running interference for him, but I wasn’t supposed to let the mask drop in front of Elaine. Still, at Falk’s elbow, I tried to help as best I could to extricate him from the woman’s grasp. She pleaded with Falk to have dinner at her house with her, her husband, and their sons, all of whom loved him like she did. Falk, nearly smothered by her, tried to be gracious. “What a shame,” he said, as he unwound the woman from his body. “I’ve got to work tonight, but thanks anyway.”

“Hi, Columbo.”

“Hey, Columbo.”

Flashbulbs were in full frenzy. Guards, still trying vainly to admit only the invited or the privileged and to control the mob, were shunted aside. Even the guards wanted to look at Columbo and speak to him.

John Cassavetes, looking heavy at the waist due to a too-tight shirt complete with colors and stripes befitting the hood character he plays in the film, was not the object of adulation that Peter Falk was. Falk was dressed in a soft suede sports jacket. Many in the crowd seemed upset that he wasn’t wearing Columbo’s trademark trench coat.

As John Starke and I pushed into the mayor’s office directly behind our stars and Miss Rolands, Elaine May was pushing out.

John looked at me and said unbelievingly, “Now where’s she going?”

“To pee?”

“She’s bolting!” said John.

She was looking for a telephone, it so happened. A weird time to make a call. She looked like a hoyden, a confused child in this noisy crowd, tall for her age, a tomboy picked up off some softball diamond wearing faded jeans and a jacket. Once the guests and the mob of reporters got herded inside, the doors to the mayor’s inner office were closed behind us, and here we all were without the director.

Nobody knew who she was. I wondered if she’d be let back in.

Peter Falk and John Cassavetes posed dutifully standing, with Mayor Rizzo sitting in his chair at his desk. Photographers positioned and repositioned themselves to get the best shots. Frank Rizzo had the dazed look of a heavyweight prizefighter after too many blows to the head but still a winner, arms raised, grinning. He had never seen this many reporters and photographers. Rizzo, a big Nixon supporter, had a face as straight as Vice President Agnew’s, which probably didn’t help him much since the Watergate containment was coming apart daily at the seams. He may not have been the size of the great Italian boxer Primo Carnera, but alongside Peter Falk and John Cassavetes he gave that impression. Rizzo invited Falk to sit in his impressive swivel chair. Falk did. A reporter asked Falk why a film company would want to film a crime drama in Philadelphia, an obvious political needle since Rizzo was having internal (City Hall) as well as external (the streets) criminal problems. Recognizing the question for what it was, Falk had an adroit reply.

“Not because of the crime,” he said. “There’s no crime in Philadelphia.”

It got a big laugh.

Falk and Cassavetes concurred that they found Philadelphia more to their liking than they could have possibly imagined. They did lay it on a bit thick. “You can even walk the streets without fear,” said Falk. Rizzo smiled slightly and looked pleased for the cameras.

“I don’t understand Philadelphia’s bad rap,” said Falk. “Mention Philadelphia anywhere in the country and they laugh. It’s a joke. Why is it a joke? Because of W. C. Fields. What was it he said—you know, the inscription he wanted on his tombstone?”

John Cassavetes was pleased to supply it. “‘On the whole, I’d rather be in Philadelphia.’ It’s his epitaph.”

It was all going a little fast for Rizzo. He wanted somebody to explain it.

“On the whole, he thinks he might prefer Philadelphia to being in a grave, or perhaps in the hereafter,” explained Falk.

He should have left it ambiguous. Rizzo was indignant. “Who said that?” he demanded. He looked angrily at Cassavetes as if it had originated with him.

“W. C. Fields, I think,” said Falk, bemused by Rizzo’s peevishness. The whole scene was showing signs of turning into a public relations disaster. “W. C. Fields was born in Philadelphia, you know.”

Rizzo glowered at the snickering reporters. He was an ex-cop. He plainly wanted to arrest someone. Anyone.

“Elaine May was born in Philadelphia too,” contributed John Cassavetes, trying to skateboard off a touchy subject and careening into the rock wall of Rizzo’s lack of knowledge about Hollywood. The mayor didn’t know who Elaine was. I wondered if he knew who W.C. Fields was. Elaine had slipped back into the room and was seated on a couch against the rear wall.

Again the still-glowering mayor asked, “Who?”

“Elaine May!” exclaimed Falk. To him it was an explanation in itself. The whole conversation was preposterous. Falk was about to break up.

I’d been aware that Elaine was sitting a few feet from where I stood and that she was trying to be polite to a woman who had surmised that Elaine had something to do with the movie. She was pitching Elaine about a Fourth of July program she was planning for Independence Hall in hopes that Elaine might use her influence as the director’s assistant, or whatever she was, to get the stars there.

“Come on up here, Elaine,” coaxed both Peter and John.

The press swiveled to look. Elaine reluctantly rose to push her way through the crowd to be introduced to Mayor Rizzo. One or two photographers took pictures. The others couldn’t be bothered.

Cassavetes introduced her to the mayor. “I was just telling His Honor that you were born in Philadelphia.”

“Oh?” said the mayor vaguely, still confused as to who she was. “When was that?”

With her many years in show business, Elaine recognized this as a throwaway line. She responded with a throwaway smile. John Cassavetes laughed at nothing in particular, directing his laughter to his shoes.

After giving Elaine May the quick once-over, Mayor Rizzo looked across the heads of the crowd in search of someone. “But where is your director?” he asked, mystified. “Let’s get your director up here.”

He meant Mike Hausman. I think.

Peter Falk, embarrassed, said with a small flourish to Ms. May, “But this is our director.” Rizzo stared at Elaine in disbelief. Falk added, trying to cover the faux pas of Rizzo’s expression with what he hoped was a pleasantry, “It’s the age of Women’s Lib, you know. Now it’s come to Hollywood.”

After Rizzo presented each of them with autographed coffee-table picture books of Philadelphia, Elaine May returned quietly to the back of the room while the clusters of reporters gathered around Falk, Cassavetes, and Rizzo. During much of the exchange I had stood off to the side whispering with Gena Rolands. While Elaine was distracted with Rizzo, I circulated, surreptitiously distributing press handouts I’d prepared giving information about the film.

With the mayor’s part in the press conference officially over, Cassavetes tried to explain the film’s premise and story line to reporters. He beckoned me to help him out. “You have something on it, don’t you?” I handed him some of the fact sheets, which he passed along to reporters. Elaine saw it all. So did Mike Hausman, who caught my eye and winked.

Elaine beckoned to Gena and whispered into her ear, shielding her mouth with her hand. Who was I? she wanted to know. Gena said she didn’t have a clue. “But I saw you talking with him,” said Elaine.

“Do you think he might be with the mayor?” said Gena, enjoying the conspiracy of silence about me.

Mike Hausman said we had to leave. Peter Falk said, to no one in particular, “Get me out of here!” Newly emboldened by the excitement and by my own tentative steps toward assertion of professional identity, I took hold of his arm and forward-pushed and stiff-armed him out the door and into the corridor, where we were immediately surrounded by Columbo lovers, importuning. Pencils and scraps of paper were pushed forward. Falk stopped and signed several.

Somebody whispered to me that the other members of our party were waiting in the lobby. Rather than wait for the elevator, we opted for the circular stairway, taking it at a fast clip before other Columbo fans gained on us. In the lobby at the foot of the staircase Elaine May was waiting for us. Her bent arm rested on a stanchion. She watched our descent with curiosity. I felt her eyes on me every step of the way. I was aware that my face was being memorized. Peter Falk and I reached the main floor with no words spoken between us, and I got the feeling that neither he nor John Cassavetes wanted to compromise my shaky position with Elaine any more than it already was.

I said nothing.

She said nothing.

I parted with Falk, made eye contact with no one but John Starke, walked briskly to the exit with him, and was out of there.

At the hotel I made notes, showered, and turned on the local evening news coverage of the event. There was a lot of Peter Falk and Mayor Rizzo but little of Elaine May and John Cassavetes except for an almost subliminal glimpse of Cassavetes, in high spirits and humor, laughing and nudging Elaine to step forward and assert herself, and Elaine, highly amused, nudging Cassavetes back with her shoulder, daring him to do likewise.

Then I treated myself to a cocktail and a wonderful dinner at a restaurant recommended by Nola. I had learned to place great trust in Nola’s recommendations.

One day I had encountered her in a local health food store. I was picking up a cup of Dannon plain yogurt. Nola said with a slight discouraging shake of the head, “Elaine eats Erwin.”

I had never heard of Erwin yogurt. My hand hesitated over a container. “Oh, try it,” said Nola, “you’ll love it. Put the Dannon back. Erwin has a thin crust of cream. Don’t look at the price. It costs more but quality always does.”

There was a distinct difference in price: Erwin, fifty-one cents for seven ounces, thirty-three cents for Dannon. Nola pronounced it a pittance. She handed me the Erwin. It would be a discovery and an adventure, she said. “Splurge.”

I found out that Elaine also had an enthusiasm for a beverage supplement “from a combination of protein sources” called Tiger’s Milk. Later when I mentioned that to Peter Falk, he said, mocking Elaine’s enthusiasm while remarking her energy, “Seriously, I think she milks her own tigers.”

The Philadelphia Daily News feature on the meeting at the mayor’s office carried a photo of Falk, Cassavetes, and the mayor.

Columbo, the idol of every cop in America looked a little beat, like maybe he had been out all night working on a very important case and needed a little sleep to get moving again . . .

Columbo really had been out all night—shooting scenes for the movie Mikey and Nicky, an underworld flick being filmed on Locust Street. Columbo is not Columbo in the movie, though. He is Mikey, a Greek gangster. John Cassavetes is Nicky, another Greek gangster.

The filming starts in early evening and goes on until dawn, which means Columbo doesn’t get to bed until 8 in the morning. But yesterday he got to visit an old cop who made it big in politics. It must have been a hurried trip because he forgot his trench coat, the Columbo trademark.

This ruined Frank Rizzo’s opening line.

“My daughter told me to tell you to get a new trench coat,” the Mayor said.

“She’ll put me out of business,” Columbo said.

John Cassavetes received a mention, but there was none for Elaine May.

That evening I got off the elevator in the Warwick lobby to find Nola, Mike, and Elaine immediately in front of me. They were conferring and didn’t see me. Nola stood removed from them by a pace, waiting to be admitted into the conference. Mike was laughing and recalling anecdotes to Elaine about the press conference. He mentioned the story and pictures in that day’s News. He picked one off the hotel newsstand rack. Elaine glanced at the photo and smiled. At that point Mike spotted me. Thinking that my moment surely had come, I stepped forward to be introduced.

Nola Safro’s hand reached out to restrain me, and Mike did his familiar blanch. Executing some nimble choreography, he stepped between Elaine and me. While facing her and throwing nervous banter, he motioned me away. The gesture was redundant. I had already gotten the point: I was still persona non grata. I back-stepped to the nearest elevator.

I had finished reading Sleeping Beauty and Howard’s End and was almost through with The Digger’s Game, a new George V. Higgins novel. I knew every interesting bar in Philadelphia. I spent Memorial Day weekend in New York. My friend Jonathan would come down to visit me the following weekend. I wasn’t sulking.

I wrote notes to Peter Falk and John Cassavetes which I slipped under the doors of their suites. There would be no opportunity for interviews, but I passed along the more important requests just the same. The Mike Douglas Show, originating in Philadelphia, was especially eager to have them. Schedules wouldn’t allow.

And there was the cop who had been calling me for two weeks about Peter Falk. The man was in charge of getting celebrities to visit sick and dying ex-policemen in hospitals. His eagerness to land Falk for this purpose bordered on the abusive. He could not comprehend the meaning of a tight schedule. Dutifully I kept feeding the request to Falk. There was one dying retired cop in particular who was “going fast,” and it was his last wish that he get to see Columbo in the flesh.

Falk called me in my room Saturday just after noon. I was on the way out to lunch with my friend from New York. After lunch we had planned to see the Liberty Bell.

“I guess we ought to do this one, right?” said Falk.

I said I thought we should. I would arrange it. The police would send a car for us, I had been told, and it would take about ten minutes each way. They had promised to have Falk out of there in less than fifteen minutes. Falk sighed. He had heard it all before. He would be gone at least an hour and a half. “Well, okay,” he said.

I called the cop to tell him that Falk was prepared to go. The cop said in mournful reproach, “Too late, the man just died.”

When I got the chance, I told Peter Falk that I’d like to sit with him and get his answers to questions Paramount wanted to pose for use in a press kit feature called “Roundtable Discussion.”

“Where did you get the questions?” Falk asked.

“I made them up.”

“Then make up the answers to go with them.”

I laughed. He laughed. “I’m not kidding,” he said. “It’s all a bunch of you know what anyway. So you make up the answers. You can do it better than I can.”

I told him okay but that I would show him the answers so he could correct them.

“I don’t want anything to do with them,” he said.

Cassavetes, on the other hand, invited me to his suite where he answered each of my questions, some at length, then listened to those I’d written for Falk. He thought it hilarious that I should have to make up the answers. He helped me with some of them and got a kick out of doing so.

Of course, Falk’s “answers” were predicated on what I knew about him. Cassavetes wondered if it was in good taste to refer to Peter Falk’s false eye.

My question: How do you remember your childhood? (Like the false eye, what problems did it create for you in your relationships with friends, at school, in your aspirations? And later, re your interest in art?)

I justified the question as legitimate. I’d seen the matter discussed in stories and biographies of Falk. The answer I gave, taken from source materials, was: “My eye was taken out when I was three years old. A malignant tumor. I was self-conscious about it, the glass eye, until about the time I started playing ball and going to the gym. Then it became a joke. From then on I could live with it.”

Cassavetes still had a copy of the production notes I had distributed at the press conference. He took me to task on a couple of points. I had referred to Elaine as a woman director. “Ah, but she isn’t,” said Cassavetes with a point-making smile. “She is a director who happens to be a woman. That fact out of the way, she is the finest actor’s director I’ve ever worked with.”

“Really?”

“Yes, really. Why do you say ‘really’? Are you surprised?”

“Kind of, I guess.”

“Why?”

“Well, it’s a terrifically complimentary statement to make about a director, particularly this one.”

“Why particularly this one?” he asked.

“The way I hear she works. Some interpret it as the method of a director . . .” (I searched for words that wouldn’t offend. I couldn’t find them) “. . . who hasn’t got a clue as to what they’re ultimately up to.”

Cassavetes smiled, shaking his head. “She knows. Believe me, she knows.”

I had heard the story of the fake stairs at the Essex, for instance. For the film, the Essex’s lobby had been redesigned and made smaller. The original stairway from the lobby to the second floor was unusable. When Elaine prepared to shoot the lobby scene, she became disenchanted with the location of the stairs. Where they were negated some specific action and business that had just occurred to her. The scene had to be postponed while the set was redesigned and the stairs located elsewhere, a delay of at least a day. I suggested to Cassavetes that another director—indeed most directors given such a situation—would simply have re-thought, re-staged, re-choreographed the scene and worked with what was there.

“And with another director you could conceivably get a piece of hackwork,” said Cassavetes. He hastened to add, no doubt sensing that I was going to, “And conceivably not.”

“Why do you say she’s the finest actor’s director you ever worked with?” I asked.

“She gives, or suggests, or makes available so much for an actor to work with. Aside from in this instance providing the script which she wrote herself, and let me tell you it’s one of the tightest I’ve ever read. She provides the props, the set – having worked it all out in advance with the prop guy and the art directors – and so forth. And she has a concept of character and direction that allows for flexibility in the actor’s development of his characterization.”

I asked Cassavetes, who was known as one of the industry’s top improvisational directors, if he expected to contribute any directorial input in the making of this movie.

“Oh, come on!” he said. “This is Elaine’s. I’m merely acting in it. She’s a joy to work with. I can hardly wait to see the movie.

“As for improvisation,” he continued, “I think singling me out as an improvisational director, or singling Elaine out, is to impose a category that I question even exists. I mean as something apart. What director directing films doesn’t improvise?”

He mentioned Frank Capra as a case in point and as a surprising influence on his own work. He had recently read Capra’s autobiography. “Like Capra says, no two directors work alike. In the thirties, Gregory La Cava and Ernst Lubitsch, for instance. Lubitsch approached his films like an architect. His scripts were as highly detailed as blueprints. La Cava couldn’t be shackled to the chart systems of a script.

“But no director can be. I don’t think even Lubitsch was. Actually making the movies is like doing the final draft of the script, especially for the director like Elaine who has written the script. No, I take it back. I guess editing is the final draft, but the director has a hand it that too, or should have.

“I’ve had a script for every film I ever did except Shadows. I had a script for Husbands. I had a script for Faces. I had a script for the new one.” (A Woman under the Influence, on which principal photography had been completed, the editing of which Cassavetes interrupted in order to appear in Mikey and Nicky). “Wrote them myself. But a director has to let the scenes and the script breathe, expand, amplify.

“That’s what Elaine’s doing with this picture. Only with this difference: after she has allowed you, the actor, to open up, expand, really explore the character and situation in a certain scene, she’ll guide you back, funnel you back, into the script.

“In the first scene, Peter and I played it every possible way, we’re all over the room. Sometimes we said the lines Elaine’s written, sometimes we didn’t.”

“Doesn’t she complain?” I asked. “You said it’s the tightest script you ever read. Why can’t you respect its tightness?”

“It’s because we respect its tightness that we can play with it,” he said. “She would never ask that it always be done just the way she wrote it. Because something better might come out of it. A line, a quality, a mood. Like I say, filming the scene is like doing another draft. Oh, believe me, she goes back to the script, believe me she does. I got a note from Nola last night.” He showed it to me.

Elaine says learn the lines.

“I’ve learned the lines. She knows I have. I’m just not married to them. I’ve never expected any of my actors to marry themselves to my lines. What this note says is, ‘Now let’s get back to the script.’ Tonight, then, thanks to this note, I will speak the written lines. Sequentially.”

One evening I planned to have dinner with our editor, John Carter. Before we finalized out plans, I was invited by our old friend from City Hall, Betty Croll, to have dinner with her and her husband at an Italian restaurant of some repute. I asked if Carter might join us. They were delighted.

I picked Carter up at the editing room. We were going out the door when a phone call came from the set. Elaine. Could Carter please hurry over to the Essex to confer with her? I called Betty Croll and told her we might be late.

At the hotel, Carter disappeared upstairs while I sat with Peter Falk in a booth on the main floor. He had a chessboard and pieces on the table in front of him, a game frozen in progress. Unlike acting, chess is something Falk refuses to improvise. He takes as long as twenty minutes to make a move. He was glum, preoccupied, in no mood for conversation. I slid silently from the booth and busied myself elsewhere until Carter returned.

On our way to the restaurant, Carter told me what the meeting with Elaine was all about. She needed advice on how to move her actors from one playing area to another to accommodate snippets of the scene that, wildly improvised, had already been shot. She wanted to match those sequences with what she hoped would now be a close adherence by the actors to the structured script. It wasn’t going to be easy.

I had my spies on set. The crew. Especially those I’d worked with before. I was fed anecdotes, items, observations.

Randy Munkacsi’s problems as stills photographer were almost a match for my own. Elaine excluded him from many set-ups, sometimes arbitrarily, sometimes excusing it to lack of space. At times she would allow him to stay but tell him, “Don’t shoot this.” Ordinarily a stills photographer is allowed to shoot during camera rehearsals. Elaine didn’t believe in camera rehearsals. She filmed her rehearsals, fearful that she would lose an inspired bit of spontaneity if she did not, some great piece of business, or some expression that might not be recaptured on succeeding takes. The sound of the stills photographer clicking away could be a distraction and might also be recorded by the sound equipment. As a result, Munkacsi was severely limited in what he could shoot and resorted to being as surreptitious as I. When I left Philadelphia at the end of my three weeks, I hadn’t seen a single contact sheet of Randy’s work. Usually by the third week of a film I have seen and usually captioned at least thirty contact sheets with approximately thirty-five exposures per page. Randy was even restricted from taking production shots: photographs of technicians at work in conjunction with actors or in setting up scenes, shots of the director off-camera doing her job. Elaine simply did not want to be photographed, didn’t want to see a camera pointed even vaguely in her direction.

“You didn’t take a picture of me, did you?” she would scold.

Randy learned to fudge. “It was a shot of Cassavetes,” he would say, neglecting to mention that Elaine was also in it. Once he admitted, “There might be just a portion of you in it.” She replied, “I hope it’s not the portion I think.”

Randy complained to me during the second week of production, “It’s getting so that every time I raise my camera, she gives me a dirty look.”

A gaffer from California said, “I’ve never seen anything like the way she directs. We’ll have the setup one way, then she’ll get a wild hair and decide to do it another way, and we have to change it. I’d tear my hair out if I had any.”

I suspect that Elaine’s style of directing was more difficult for the cameramen than for anyone else, especially the focus cameraman. The actors had no set marks to which they had to adhere during scenes. “The trouble is,” a cameraman told me, “they can move wherever they want whenever they want, and we’re supposed to keep them in frame and in composition and in focus.” Small wonder the original director of photography and his focus cameraman left after a few days' shooting.

There were complaints that she couldn’t do “pick-up” scenes: scenes in which the actors pick up dialogue at a specific line or bit of business and reenact for the camera only the required portion of the scene rather than the entire scene. “Invariably, she’ll reshoot the entire scene rather than do a pick-up,” said an assistant director. “She doesn’t edit in her head.” Needless to say, reshooting the entire scene is costly in money, temper, and time. Although the method had paid off for Elaine in her previous two films, A New Leaf and The Heartbreak Kid, very few (if any) other directors would have been allowed the leisure and license she enjoyed on Mikey and Nicky.

On Thursday, June 7, the exhausted company finally finished at the Essex Hotel; and so glad was everyone to get out of there, it seemed almost like a wrap. It must have been because of the prevailing mood that I dared slip a note under Elaine May’s door. “Don’t shoot, but I’m the publicist,” it began. I went on to tell her that Guy Flatley wanted to come to the location to do a Sunday “Arts and Leisure” piece for the New York Times, focusing either on her as director or on the film. “If it’s impossible to speak with you, he’ll be happy just to do a production story.” I pointed up the advantages.

The note was intercepted by Nola Safro.

“I found your note,” she said, with an enigmatic smile on her face.

Oh God! I thought. Is there no way to pierce this barrier?

“Did you show it to Elaine?”

She shook her head slowly. “It’s best she doesn’t see it.”

I tried not to let my frustration give rise to anger. Nola was not unsympathetic. She knew a Times story was important. However, Elaine had already promised another Times movie writer, Mel Gussow, a story. “When the time comes, she’ll give Gussow a story, but not till the picture’s finished.”

Gussow wrote for the daily paper, Flatley for the Sunday edition. Why couldn’t each of them have a story, I argued. “She doesn’t even have to talk to Flatley. Just let him come visit for a day or two.”

Nola looked at me with pity. I still didn’t get it, did I? I still didn’t realize just what we were dealing with. Her look gave me a small shiver.

One morning I was sitting at someone’s vacant desk in the production office when Elaine came in and sat down at a desk in front of me. If she noticed me, she gave no indication. She wrote something on a notepad, tore out the note, and went to the editing room. It was the first and last time I saw her in the office. It was like working with Garbo.

When Elaine returned from the location at eight in the morning, she sometimes went directly to the editing room for two or three hours before finally retiring to her suite. The doors to the editing room were always tightly closed. John Carter had been given two assistants and additional equipment to help deal with the voluminous amount of film being shot.

On the next to the last day of shooting at the Essex, John Cassavetes accidentally struck a female extra with a bottle thrown from a second story hotel room window supposedly to land at the feet of Mikey (Peter Falk), who was standing in the street below. He aim was off and the bottle hit the woman in the head. She was rushed to the hospital.

Thursday’s papers carried the story along with the additional information that the woman was filing suit for $10,000. Cassavetes visited her in the hospital. Falk wrote her a letter describing her as “. . . a terrific person . . . really nice.”

The bottle is crucial to the action. Nicky is holed up in the downtown hotel room. It’s night. He’s desperate, certain they’re out to get him. He needs help, medicine, food. He’s got an ulcer. Who can he turn to? Who but Mikey, his childhood buddy with whom he had joined the syndicate or gang (anything but mob or Mafia) on a buddy basis like some guys join the Navy. But what if it’s Mikey who has the contract on him? Trusting no one but with no one else to trust, Nicky calls Mikey and tells him to come to a certain street corner and come alone. Nicky has to make sure that Mikey is alone. Once certain, he’ll let Mikey know how to find him.

Now comes the bottle and the towel.

When Nicky sees that Mikey is alone, he wraps a towel around a bottle and throws it into the street to land at Mikey’s feet. A clue to his whereabouts. The name of the hotel is on the towel. Mikey gets the room number from a recalcitrant clerk, rushes up to Nicky’s floor, and raps on the door. Nicky, still apprehensive, won’t open the door.

“Come on,” cries Mikey, “it’s me, Mikey. I came as soon as I got your towel.”

A funny line. Quintessence of Elaine May.

Then I heard they weren’t using it in some of the takes. I told Jackie I thought it a crime if they didn’t use it. It was too good a line to waste.

“I don’t think it was there originally,” Jackie said.

“What do you mean, ‘originally’?” I asked.

“It wasn’t in either the play or the script,” she said. The work had started life as a one-act play.

“You mean she just recently added it?”

“No,” said Jackie, “I think they might have.”

They could only mean them. “You mean Falk and Cassavetes came up with it?”

“Hey, that’s how they work. It’s how they all work. Of course I don’t know. I admit it sounds like Elaine.

So much so that I said, “It has to be Elaine.”

“Maybe that line,” Jackie said, “but they put some things in. They got together and rehearsed long before any of us ever saw a shooting script.”

I decide it must have been in rehearsals that the script turned into a comedy. In the process of filming it, Elaine was trying valiantly to reposition it on its dramatic foundation.

“It’s what worries Elaine so much,” said Jackie. “Everybody thinks it’s going to be a comedy. It’s what they expect of her. It is kind of funny though, isn’t it?”

She said that Elaine complained about being unable to resist laugh lines and situations that occurred naturally to her comic imagination but that had no relevance to the tone and mood of the scene. Sometimes she didn’t resist but realized it would be something else she would have to worry about later in the editing room.

It was editor John Carter who brought me the big news about myself: Elaine was considering me for the third male lead in the movie.

“What!” (Actually I think I had at least three exclamation points in my voice.)

“Yes,” said Carter. “She’s seen you around. She thinks you’d be great as the killer in the car.”

I couldn’t interpret the smile playing about his lips. Was he putting me on, or was she doing so using him as her conduit? Carter was not one to play practical jokes or speak frivolously.

“You say she’s seen me. Where?”

Carter shrugged. “City Hall, for one thing. You’ve been on the set a couple of times. She’s seen you with me. Yours is a familiar face to her now. She wants a familiar face in that role.”

The killer/contract man had little dialogue. His role consisted primarily of driving an automobile though the dark late night streets of Philadelphia or sitting in the parked car waiting for his mark to appear.

I was never approached officially about the role. Elaine decided that Paramount president Frank Yablans should play it. He refused. She then offered the role to Bob Fosse. When he turned it down, Ned Beatty was cast. Carter assured me (or teased me) that Elaine did have me marked as camera potential and would use me yet.

On the night of Friday June 8, the company was filming at Dewey’s Coffee Shop at Fifteenth and Locust Streets, not far from the Warwick. In the scene, Mikey comes into the coffee shop at a gallop to purchase either cream or milk for Nicky, whose ulcer is acting up. Nicky has a stopwatch, and if Mikey is not back at the hotel with the milk in ten minutes, Nicky will know that he has taken the extra time to tip off the mob as to his whereabouts and that it is he who has the contract on Nicky. The scene involves a confrontation between Falk and a slow, obstinate counterman who refuses to sell Mikey any cream unless Mikey also buys the coffee that the cream would ordinarily be sold with. Argues the counterman, otherwise how would I know what to charge for the cream? (It had struck me as sort of a riff on the famous restaurant scene with Jack Nicholson in Five Easy Pieces.) A brief scene, really, just a page and a half out of some129 script pages.

The counter was a kidney-shaped affair with a wide, gleaming, Formica-slick surface. On the far side of the counter, out of camera range, sat a multitude of extras, only a few of whom would be used. Standing in front of the counter, Elaine whispered to her assistant director, Pete Scoppa, while looking circumspectly at me. Scoppa was already in costume and makeup to play the counterman. He tried to follow her discrete indication. His range was afield. She focused him on me. He shook as head. As did crew people. She argued with them, all of them looking in my direction while pretending to look beyond me.

I was starting to feel that maybe there was virtue in staying in my hotel room.

Elaine wanted to use me in the scene. Scoppa told her she couldn’t. I wasn’t an extra. She had contracted for extras. She was paying for extras. “Use an extra,” he told her.

Later he told me the real reason they wanted me instead of an extra. “We expected violence.”

I don’t know who they told Elaine I was. We were still maintaining the fiction that there was no publicist with the company. None of the extras had the look she wanted, she told Scoppa. The look that I had. I wonder what that look was. She capitulated sullenly and picked a male from the pool and placed him on a stool at the counter. She looked at him through the camera lens and immediately had him returned to the pool. Another was selected who also didn’t meet with her approval anymore than the first. He was dismissed. She looked longingly at me. Pete Scoppa shook his head in grave discouragement. She looked vaguely around for another idea.

Someone or something for Peter Falk to play off. And there they were. They had just been brought in.

Doughnuts.

Sitting almost directly opposite me on a table behind the counter, the doughnuts were to be used for decoration and props. They were in a fresh, grease-stained, highly fragrant cardboard bakery box, gorgeously glazed, tempting even to someone like me who avoided pastry as the harbinger of hypoglycemic plague.

Elaine fixed on the doughnuts. She began fondling them. Carefully. Appraisingly. One by one. Testing them for – whatever. Firmness? Weight? Who knows. Bob Visciglia, whose province as prop man the doughnuts were, joined her in the exercise. He fondled the doughnuts too. I doubt seriously whether he had any more idea what he was feeling for than I did. Perhaps I do him discredit. I did admire his bravura in faking it. Doughnuts were separated. This one rejected, that one chosen. That one returned to the box to be shoved under the counter, this one proudly to go to onto a counter display plate. Some doughnuts rejected by Visciglia were reclaimed by Elaine. She had second thoughts about some of her own choices, but not like she did about Visciglia’s. Evidently he never learned the trick. She returned most of his selections to the greasy box and replaced them with doughnuts chosen by herself. There was a fair amount of anguish and soul-searching over a couple of the doughnuts before their proper niche was decided. She felt, selected, rejected, and transferred doughnuts for a period of fifteen minutes. Why some were rejected as unfit for camera and others chosen to make their wild cinematic debut was never revealed to those of us who were watching.

Once her selections had been made and placed on the display plate, she then began to arrange them to suit her artistic or esthetic sense. Some doughnuts on the bottom she pulled from the pile and put on top. Some on top she tucked in among those at the bottom or arranged somewhere in the middle. When her back was turned, a little boy, son of one of the camera operators, grabbed one and began to eat it. He was hustled outside. No one mentioned it to Elaine, but when she turned back to the plate, she immediately knew something was wrong. She was momentarily puzzled but cast no blame. She merely rearranged.

When she finally thought it was perfect, she paced the plate of doughnuts on the counter where it would be in the forefront of the shot and put a plastic orange cover over the plate. She looked at the plate through the camera. What she saw did not please her. She removed the cover and looked again. Still she was dissatisfied.

Most of the company, except for a precious few of us who were hypnotized by her obsessiveness, were oblivious to her, perhaps consciously so, immersed in business, problems, and conversations of their own.

She put the carefully organized display plate and its orange cover out of camera range. She then set the box of rejected doughnuts on the counter. She looked through the camera again, smiled. It was what she wanted. She was ready to shoot.

I asked Pete Scoppa what had been the point. His expression said, “Huh?”

“The doughnuts,” I explained.

“For Falk to work with, if he wants.”

“How?”

“However he wants. If he wants. They’re there to use if he wants to, like you’d have been if I’d let her use you. She’ll never tell him how to use them. They may suggest something to him. Like you might have. Then again he may ignore them. We’ll just have to wait and see.”

Which still didn’t really explain the fifteen minutes of feely-touchy with the fried and sugary dough.

The camera operator seemed to read my mind. Like many of the crew, he had worked with Elaine before. He told me that he had never seen her quite so compulsive. I wondered if what looked like compulsiveness might not be her way of psyching herself up for the scene. Or down, as the case might be. Perhaps she was blocking out action, testing camera angles in her head as she fiddled about. In any case, I marveled at what I’d been watching. I realized that I’d been witness to an improvised sketch containing in its own inadvertent way as much satiric wit as a Nichols and May parody, just nonverbally. But who dared laugh? It was enough, in my precarious position, just to look.

Certainly Peter Falk had been given something to work with. He had his choice of an individual doughnut, the collective doughnuts, the doughnuts and the box together in a cataclysmic orgasm of business, or portioning this wealth of material, first the doughnuts and then the box. Also provided for him were a crumpled napkin, a coffee cup with dregs of coffee remaining, and silverware lying about. Somehow it all came together in my head as confirmation of what John Cassavetes and Peter Falk had both told me about Elaine May: that she is the best actor’s director in the business, always giving the actor something to work with, beginning as a true auteur in authoring a tightly constructed plot, characters realized in depth and relating to one another in interesting complexity, dialogue that skips off the page like bullets to explode with a zing of wit upon delivery, on down to the coffee dregs and doughnut details of the night’s lunch-counter accoutrement.

Lights.

The scene was ready for filming. Since Elaine did not stage camera rehearsals, the camera would turn on every bit of action. She was after spontaneity, which she believed might come at the very beginning. She didn’t want to miss a thing.

Camera.

Action!

In his contretemps and frustration with the counterman, Peter Falk attacked the doughnuts in every conceivable way, all on the first take.

He slung them, spit on them, threw them, kicked them, and stomped them. How easily it could have been me!

Scoppa was slaughtered along with the doughnuts.

Falk’s hands were as busy as his feet. He was a madman.

The little boy who had appropriated a doughnut gasped at a particularly bit of brutal nastiness visited upon Scoppa. His mother clasped her hand over his mouth.

Watching the take, you felt for Scoppa. You wondered if he wasn’t going to come out of this more dead than alive. You sensed his astonishment and anger as well as his regret at having taken the role. Now you realized why they had one of the crew take it: an actor would sue.

The level of anger and violence exhibited by Falk was totally unexpected (except for Scoppa, surely, who having forewarned me of violence must have expected it, if not to this extent and virulence). Everyone was watching spellbound, Elaine visibly ecstatic. Falk’s performance was totally mesmerizing. One had to resist the impulse to run out in front of the camera to save Pete Scoppa.

Falk jumped onto and over the counter to clutch his hands about Scoppa’s neck and start strangling him, jerking him backwards, forwards, sideways, banging him against the counter repeatedly in the struggle. (Scoppa showed me his back the next day. It was a ribbon of welts, black and blue and purple.)

When the take was over, it took at least five minutes before Falk’s anger subsided and his breathing became normal. He strode back and forth behind the stool where I was sitting, trying to come down from his adrenaline high. He glanced at me. More like a glare. Still partially in character, I realized. Mikey still lived within him. The glare contained a plaintive quality, however, that was not Mikey’s but Peter Falk’s: the look already contained an apology. As he caught his breath, his look became gentle and Columbo-ish. I still chose to avoid his eyes. The man might have been acting but he was not kidding.

The scene was shot fourteen times that night. And that was the master shot alone. Then came the same scene with close-ups. The doughnuts disintegrated. In some takes, Falk merely threw and broke plates and stayed on his side of the counter. In others he used doughnuts like grenades. When the doughnut supply ran out, the prop man was reduced to Scotch-taping doughnut pieces together for subsequent takes. Aesthetics be damned.

Falk apologized to Scoppa after the first take, but his anger and how he acted on it, how he acted it out, was no less restrained during all of the following takes.

The most horrendous take for Scoppa, if one can be singled out, was one prior to which Elaine had taken Scoppa aside to tell him, “This time, be evasive.”

What does she mean? Scoppa wanted to know.

“Don’t give him the right answers. Don’t give him his cue. Let’s rattle him a little.”