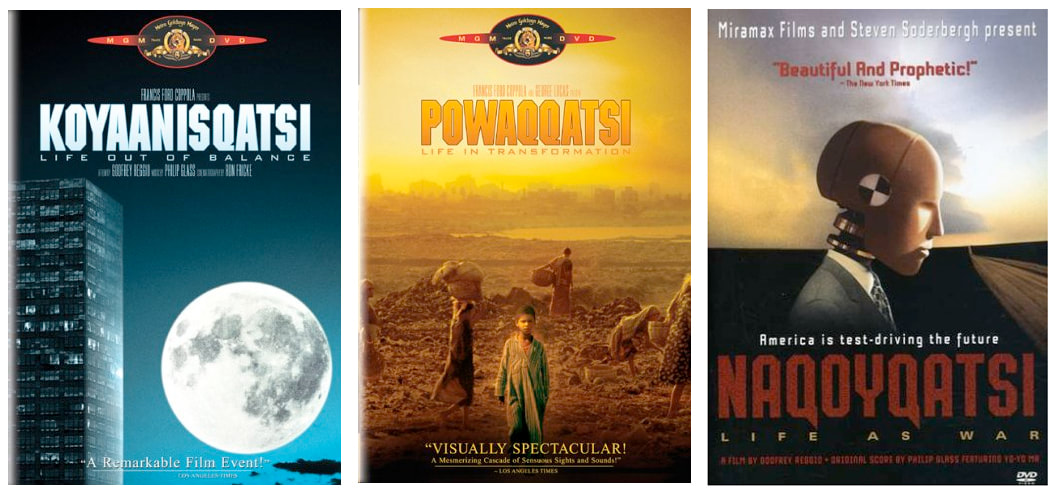

For in Reggio’s thinking and pattern, “the world” is a digital place, and this final movie is set there. Eighty percent of it is made up of extant images that have been altered in various ways digitally, and the other 20 percent shot for the movie has also been similarly twisted, torn, altered, tortured even. It is not as simply beautiful as the first two. But it has its strange fascination.

Between the time the second was released and the third one made, there had been vast strides in digital technology, and without those advances the third one would not have been possible. But there have been so much more advances in those techniques between 2002 and now, and at times one feels that this movie is more old-fashioned that the earlier ones. Sunday was the first time I saw this one, and I must watch it again, this time with a mindset to appreciate better what was accomplished at the time.

I was prompted to get the Qatsi set by a Criterion article about RaMell Ross, the director of the recent Oscar-nominated documentary “Hale County This Morning, This Evening” and the 9 minute video that accompanies it. It is of interest, and if you have not encountered it go here: https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/6197-how-the-qatsi-trilogy-gave-ramell-ross-a-new-way-of-seeing

Ross discusses his fascination with the trilogy and how that influenced his own movie. As soon as I saw the title of the piece I made the connection.

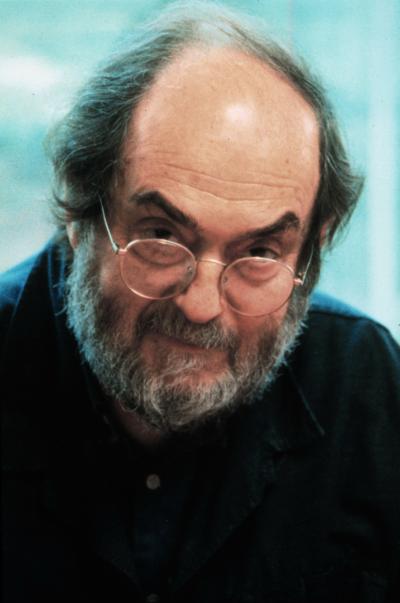

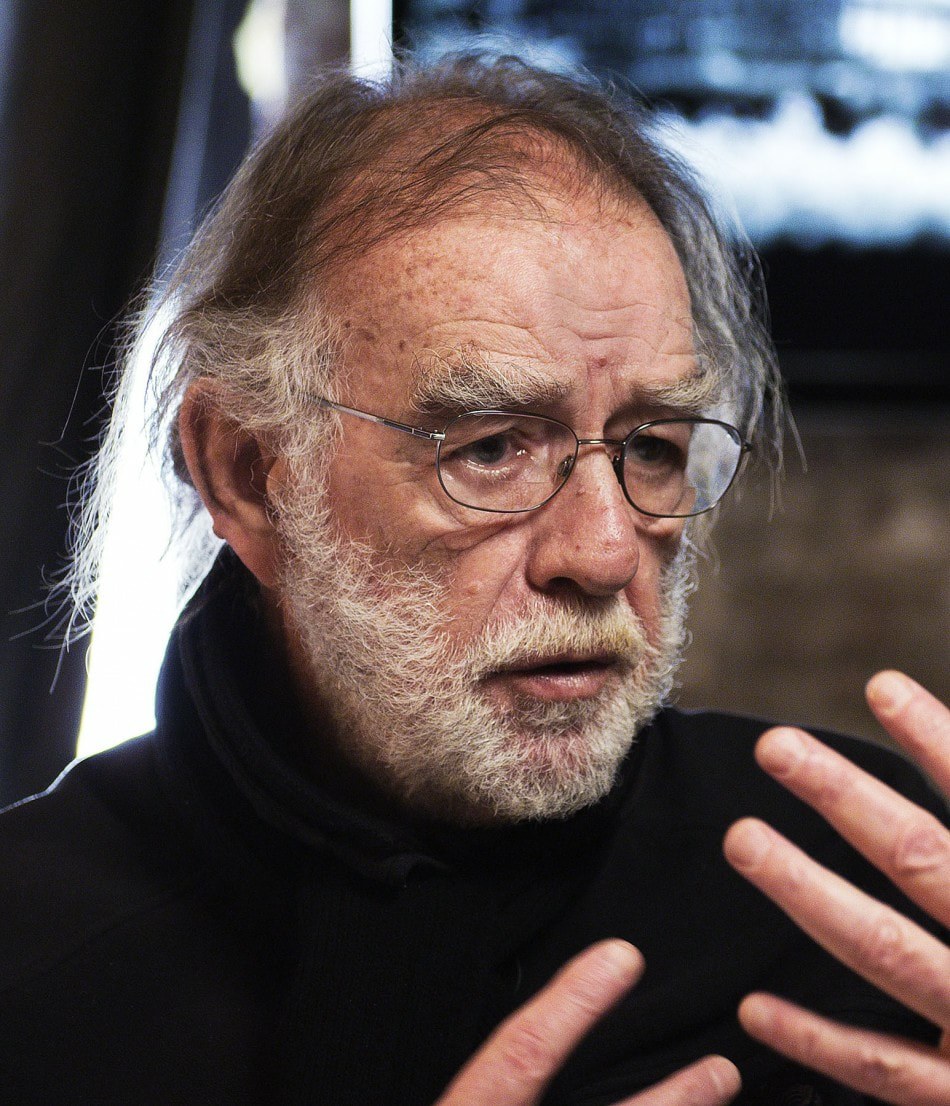

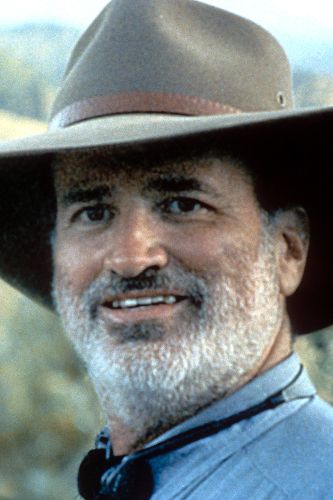

I see a through-line from Stanley Kubrick, particularly “2001,” through Godfrey Reggio’s trilogy to the works of Terrence Malick. In all of them, images and sound are presented without a lot of (or any) explanation. One watches and interprets what one sees. Some folks love that. Some folks hate that. Some folks love and some folks hate all three of these directors. I’ve loved Kubrick and Malick for many years now, and I am getting there with Reggio. I hadn’t expected that until I watched this trilogy lately and close together.

The three directors, I believe, share a spiritual quality. Or maybe it is better to say that the movies of all three directors can provide a spiritual experience. Malick has a background in philosophy, which he has taught. Godfrey Reggio as a young man spent 14 years in the Christian Brothers, a Roman Catholic religious order of men living in community, dedicated to prayer, study, and teaching; his composer Phillip Glass is a practicing Buddhist. Kubrick seems to be the outlier. He was from a Newel York Jewish background, and he seems to have drifted away from it as a religion but never denied his ties. He comes across as a rationalist, as does his “2001” collaborator Arthur C. Clarke, but that movie, with its themes of birth, death, and rebirth, certainly lends itself to religious/philosophical interpretations. I find that in other movies of his as well, notably “Barry Lyndon” and “Eyes Wide Shut,” and for me the closer to perfection even the most secular piece of art manages to be, the more it provides me with a sense of the spiritual.

All three directors are masters in the use of music. All three believe that their works should be left open to the viewer’s interpretation. All three are independent movie-makers in the best sense. They move me like the great poets do.

I can watch them again and again, for they do work more like poets than novelists. You can read the Twenty-Third Psalm or Marvel’s “To His Coy Mistress” or Hopkins’s “God’s Grandeur” and you pretty much get it the first time. Yet all can be experienced over and over again, with results that do not diminish but grow. They do not depend on plot. You read them today and you bring something new that you did not have the last time you read them. The same with Faulkner, Garcia Marquez, and a few others. I loved Charles Todd’s Inspector Rutledge series, wonderful murder mysteries that explore the effects of WW1 on survivors and the English people, but once is enough. But Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer novels, wonderfully plotted as they are, attain a level of poetry that allow me to experience them again. Hitchcock’s plots lose their power, but the poetry in his execution justifies experiencing his works more than once.

There are other movie directors close to my main line of three: Terence Davies, Christopher Nolan, Ang Lee, David Fincher believe it or not, probably Barry Jenkins and Luca Guadagnino, the Wachowski Siblings oddly enough, even Brian DiPalma, among others. Many others. A surprising number of science fiction and horror movies share some of the qualities I find it my triumvirate. Some of these artists and their works may well equal many of those of Kubrick, Reggio, and Malick.

Yes, this discussion is male-centric, but I’m judging by what captured me, not trying to make up for decades of women denied entrance into the profession of movie-making. But that is going to change. Some years ago in the ‘New York Times” I read an interview with several young women movie-makers in which they were asked about what inspired their work:

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/13/t-magazine/sam-taylor-johnson-lisa-cholodenko-sarah-polley-and-other-female-directors-on-the-movies-that-influenced-them.html

Two mentioned Terrence Malick’s “The Thin Red Line” and one his “The Tree of Life.” I particularly liked what Sarah Polley said about “The Thin Red Line”: “This film single-handedly lifted and carried me out of a depression when I was about 20. It gave me faith in the ability of human beings to create beautiful things. It gave me faith in other people’s faith.”

That could apply to all three directors in my through-line:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed