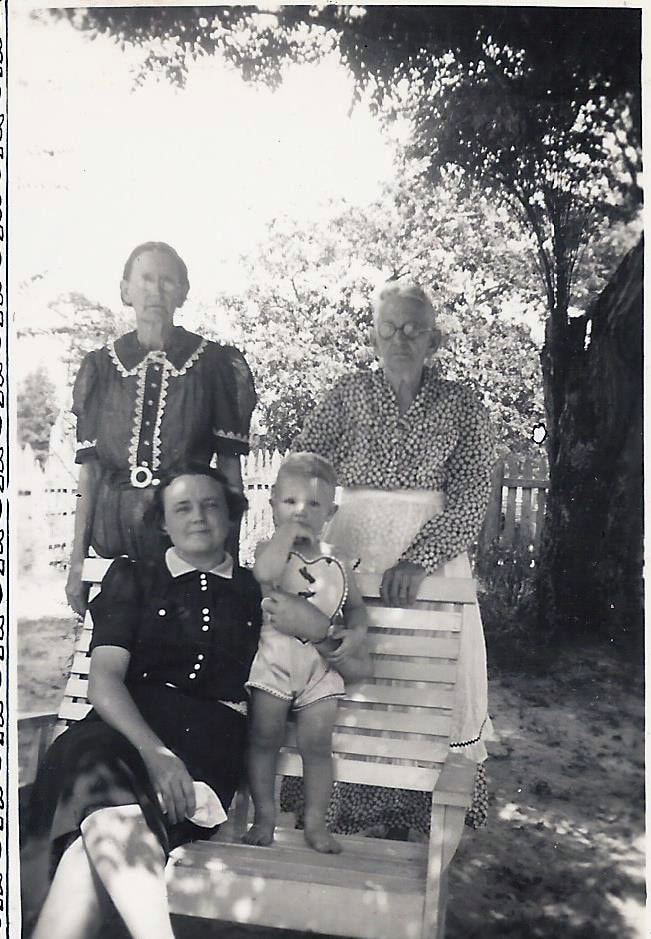

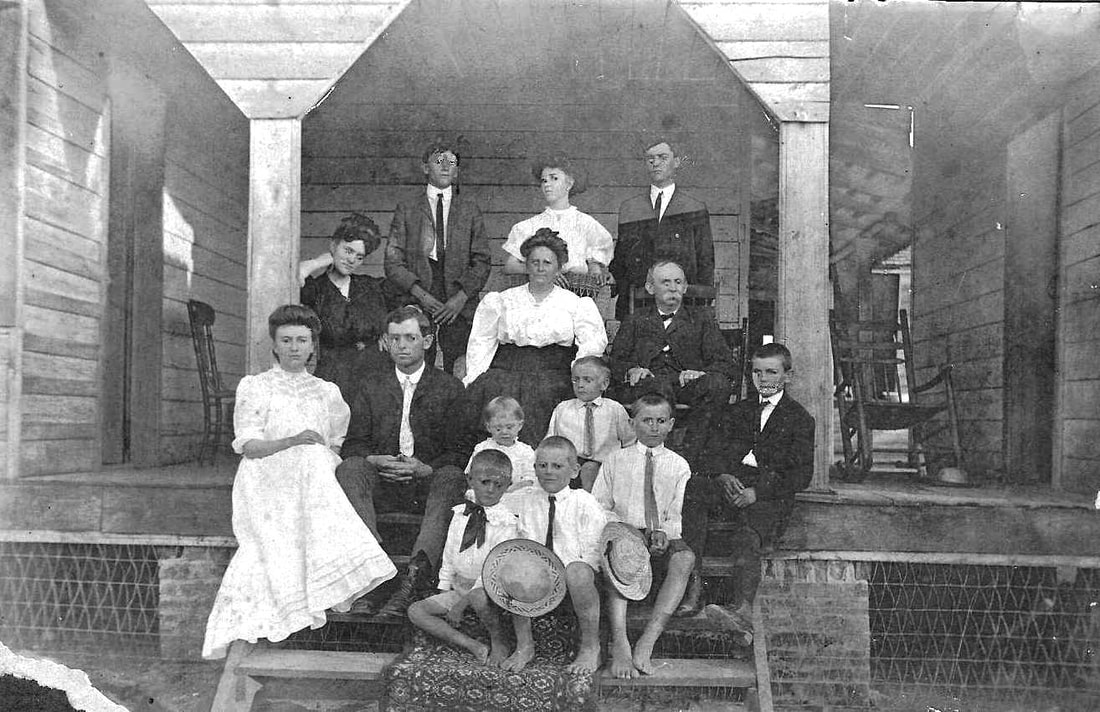

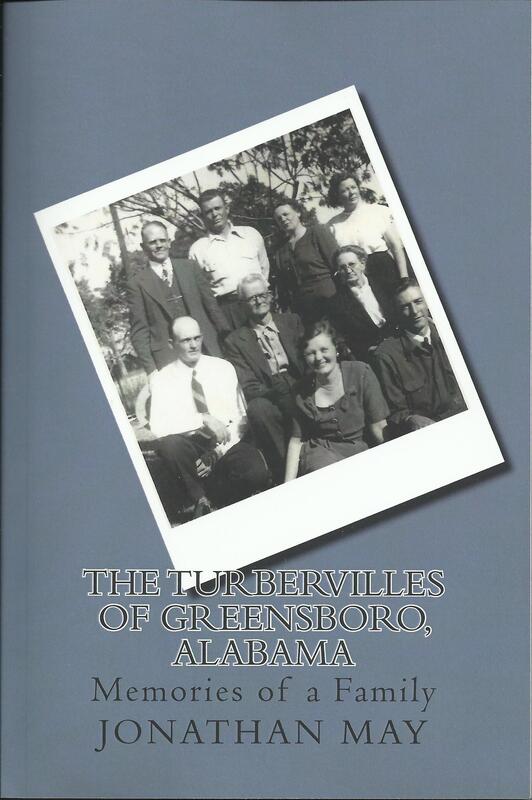

They are all dead and gone now, my grandparents Jonathan Brooks and Nicie Elizabeth Kinnaird May and King Dave and Annie Pearl Thomas Turberville and the sixteen children these couples produced, my parents and uncles and aunts. And so many others are dead as well, as you will discover. Dead, yes, but for me not gone.

That last is what this volume is all about: my memories of these people and of others and of myself over time. Notice I said my memories. I’m sure that any of my readers who knew any of these people will have their own set of memories, and I’m sure that not in every case will they match completely with mine. That’s all right. It would be wonderful if they too would set down their memories as well. Possibly my memories will jog theirs and make them think about the past and remember. I have found that writing down my memories reminds me of so many others, that being a good thing in itself.

I have tried to get facts correct when possible, and some may recall the occasional question from me about someone or something. But the memories are more important to me than the cold facts.

You’ve all heard the old expression “warts and all.” Well, this work is not quite that. Too much emphasis on the warts and you don’t notice the good stuff. Although I have not avoided the warts entirely, I believe my examination of them is restrained and judicious. I hope that I have ended up with a decent and honest set of pictures of the Mays and the Turbervilles and others without being cruel or offensive. My intent has been to be kind.

When you think about your past and the people in it you find yourself trying to fill in the blanks, to make sense out of actions and relationships in order to attempt to see the whole picture. You have to interpret, extrapolate, imagine. I have done a good bit of that, and I have tried, either directly or implicitly, to indicate when my own interpretations come into play.

One interesting and odd thing I learned along the way: I find that I like these people more than I thought I did. Warts and all.

The brief printed epilogue at the end of Stanley Kubrick’s movie adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Barry Lyndon reads: It was in the reign of King George III that the aforesaid personages lived and quarreled; good or bad, handsome or ugly, rich or poor, they are all equal now.

We could change the time and place from the reign of George III in England to the twentieth century and early twenty-first century United States and the words would be appropriate for so many of those mentioned.

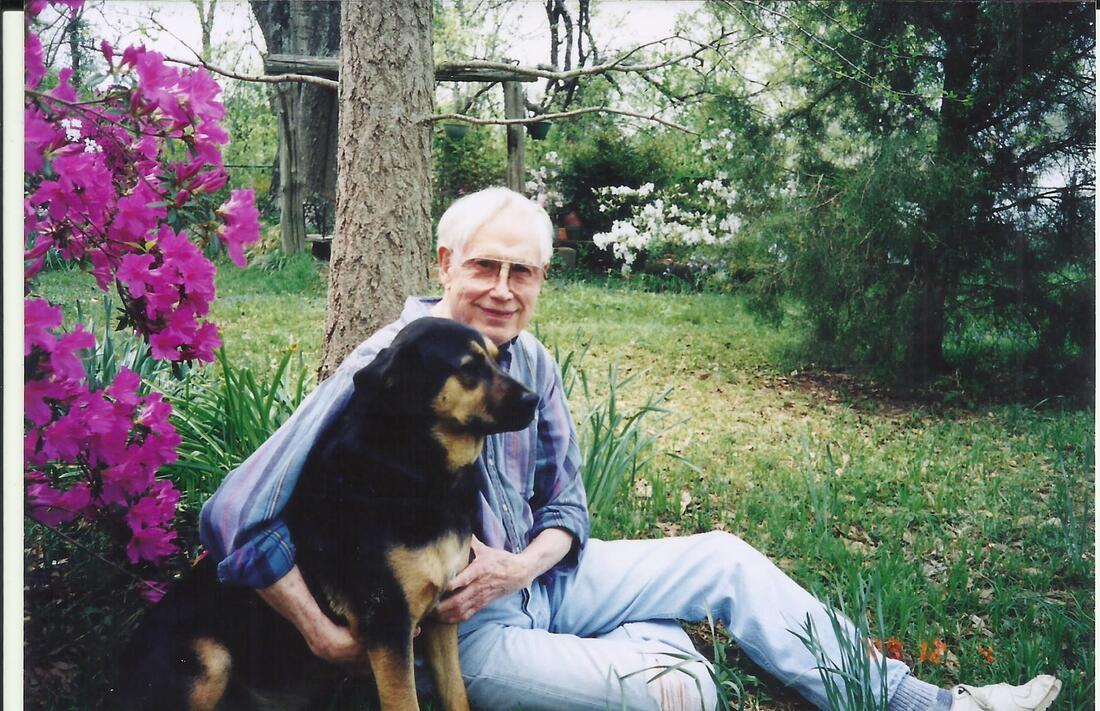

Tom is Tom Miller, who was a motion picture publicist under that name and who wrote and published under a pseudonym, Tom Canford. We spent forty years together.

Huckleberry, Huck for short, was our first dog who lived and loved with us from 1989 until her death in 1999.

Roscoe is the shortened everyday version of Orozco Cahaba, who came into our lives just a month after Huckleberry left, not to replace but to supplement. He outlived Tom by almost exactly two and a half years.

For the same reason I also reedited and self-published at long last my first-written novel, Siren Song, and I revised my second-written but first published novel Rumors of Wolves and published it anew under the title A Howling in the Night.

###

“Tell me a story.”

“Once upon a time . . .”

We know immediately that we are going to hear an old tale, a fairy story, a story to entertain children. Witches. Ogres. Dragons. Fairies that place curses. Giants. Dwarves. Evil stepmothers. Negligent fathers. Blood and guts.

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” We assume memories, flashbacks, violence, family, likely a Spanish or Latin setting, and the carefully chosen detail.

“Call me Ishmael.” We really don’t know where we are going, but somebody is going to be talking to us, but can we assume his name really is Ishmael? He doesn’t exactly say that, does he? Is he a wanderer? That name would suggest as much.

“Sitting beside the road, watching the wagon mount the hill toward her, Lena thinks, ‘I have come from Alabama: a fur piece, All the way from Alabama a-walking. A fur piece.’ Thinking, although I have not been quite a month on the road, already I am in Mississippi, further from home than I have ever been before.” We know her name, where she is, where she has come from, and we know that although she may be nearly illiterate we will hear at times an inner voice greatly different from her normal voice.

“A screaming comes across the sky.” Abrupt. Poetic. What is the screaming? Why does it come across the sky? We must find out.

And we keep reading.

We want to hear that story. That tale that someone has made up.

A child accuses another, “You are telling a story!” That other child is being accused of lying. Of making up something other than the truth.

Critic Harold Clurman once wrote a book of essays and reviews with the title Lies Like Truth. It was about the theater, and that’s play-acting.

The movie The Battle of Algiers (1966) in its documentary-like look seems to be “true.” But it is a reconstruction and interpretation of events that took place a decade earlier.

A “documentary” is presumed to be “true.” As is an autobiography or a history book. Or a book of essays about aspects of someone’s life.

We see at the beginning of a movie “Based on a true story.” Is that formulation telling us that the story is true or that the story is fiction?

You ask a friend, “Did you go to town today?” You begin to get a reply, “Well, I didn’t sleep so good last night, tossing and turning, and when I finally got up and looked out the kitchen window there was a dripping rain. I’d heard some wind during the night but that seems to have died down. I couldn’t make up my mind whether I needed to go to town bad enough to venture out or not. I checked my refrigerator and my pantry shelves and tried to think if there was anything I needed so bad I would have to go out in the rain, and then . . . .”

Tell me a story.

Let me tell you about my father. He was born . . .

Oh, that’s a wonderful detail. I’ll put that in. I don’t think I should mention that, it might upset the descendants of Great-Aunt Euphronia. Oh, that part is boring, let me skip to the more interesting parts. Now that is simply too revealing about myself. This I’m going to put in because it sets up the next piece so nicely and gives a hint to the overriding theme of the book . . .

Am I telling “the truth” or am I making up “a story”?

Let’s say I’m shooting a documentary for PBS about Big Jim Folsom. Here’s a great clip of him acting dumb, let’s put that in. I wish we had footage to illustrate a certain point but we don’t so let’s just skip over that part. I like what that historian is saying but he doesn’t come across well on television, let’s go with this other one who is more charismatic. Oops! Five minutes too long! I’ll go back and cut out the most boring parts.

Am I telling “the truth” or am I making up “a story”?

Once upon a time there was a town called Erie in West Central Alabama. The town has long since vanished, not overnight, but even in my ancient childhood totally gone. There was a tale current when I was a child about its disappearance. The people of the town captured a mermaid from the river, and then people in the town began to get sick and die and they decided to move the county seat across the Black Warrior River to Eutaw.

It is true that there was a story about a captured mermaid. It is true that the county seat was moved to Eutaw. But is the story about a captured mermaid true? I used the truth about the existence of the story and a few known facts (or “facts”) as the basis for my novel Siren Song. Totally a fiction. A story that I made up.

But there was a purpose in my making up the story. I wanted to look at matters involving life and death and love and sex and the passing of time in a contained environment. What I made up has some truth, at least for me.

I believe that stories, whether true or made up, do provide us with ways to structure our experience with life and its mysteries.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, to my mind an example more of a Romantic novel than a horror novel, provided a way to look at some of the implications of the growing scientific knowledge of its time, particularly at the responsibility of the creator toward what has been created, the inventor for what he has invented. I see that theme in later works as different as Terminator 2, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, even Prometheus. Bram Stoker’s Dracula looked at a lot of stuff, including fear of the outsider, the stranger, as well as fear of sexuality. Is the hunkier or prettier vampire we get today a sign that some of that fear is waning?

The “cozy” mysteries of an earlier time involved deaths and the restoration of order by a detective’s finding out whodunit. The serial killer of the latter half of the last century was, I think, a wonderful invention reflecting societal needs of the time. Mysterious random senseless deaths occur. Only as the detective figures out the mad pattern in the mind of the killer will there be closure. Things are not random: there is a pattern, a reason, even if a mad one. The zombie craze reflects societal fears of contagion in a vivid way and, perhaps, society’s desire to strike back without question at cause and carrier.

Conspiracies make great stories that try to explain What’s Really Going On. Freemasons, Watergate, Kennedy Assassination Cover-up, New World Order, the Military-Industrial Complex, the Illuminati, the International Jewish Conspiracy, the International Communist Conspiracy, the International Capitalist Conspiracy, the Gay Mafia. The list goes ever on and on. Sometimes you can take one from Column A and one from Column B and combine them. There must be a story behind the incidents of our times. Even if the stories are stories . . .

Look at that friend replying to my question about whether he went to town. A simple question, and a story emerges. The more he talks, the more details there are. I write something about my father or my mother. The more I write, the more things come to my mind. Telling the story makes me remember more of the story.

In his family memoir Baker’s Daughter, Miller’s Son, Tom says this: A memoir is a scattered thing. Like memory, it comes at you in snatches. You attempt organization, but a thought, an anecdote, leads to another and you must get it down or it goes. The memory here is Norma’s as much as it is mine, and some of it is Jane Rose’s and Betty Jo’s. I'm setting it down as Norma remembered it, or as I remember it, or as I remember being told it. I of course have notes, taken over the years, but they are in snatches like memory and almost defy organization.

When I first made use of Tom’s material in the unpublished memoir on a sort of memorial website I set up, Canford Lyrics, I selected information relating to Tom’s early years and edited with a strong hand, pulling pieces from throughout and grouping them into a more cohesive and chronological work. But in 2013, when I was readying the manuscript for publication, I had other ideas. In my introduction to the memoir I say this: The rambling and discursive nature of the original manuscript now cried out, at least to me, to be preserved. The voice sounded like that of an older man thinking back over his life and what he had heard about his forebears and telling a new generation, with one thing leading to another with connections almost subliminal and with skips over all time and topics. I liked his chapter headings and used them as they were: even if he often rambled off topic, they do give clues as to what the topics were in Tom’s mind.

I am happy with my 2013 choice. And I am not afraid to emulate that approach here. Although I will be approaching matters in a mostly chronological order, once I get a story or commentary going I may follow that thread to the end, even if that end is decades later. If I detail a hot summer love affair, I’ll follow that to the end, even if it means skipping ahead of myself some five decades.

In my own writing I find that it limits me too much if my topic is too big: Jonathan’s Entire Life, Times, Thoughts Both Serious and Otherwise, Opinions, Philosophy, Gossip, and Miscellaneous Musings, say. The Theory of Everything Jonathan. I cannot lasso a horse that big. While I was preparing material for earlier attempts at essays that involved me to some degree, I found that I worked better if I tackled only a small part of the beast. Write about two dogs, Huckleberry and Roscoe, and with them in focus let Tom and Jonathan be glimpsed in the background. And why not write something about what Sawyerville was like when I was a child, or Sadie Roberson, or the deaths of two uncles. Whatever I might write about, Jonathan can’t help but peek through. And yes, some of that material has found its way into this new work.

Let’s look at my father. My mother. Their families. Tackle one uncle and aunt at a time. Let me natter on about various aspects of my life. Maybe, just maybe, I will end up with something that is a little bit larger than its various parts might suggest.

Or maybe not.

Let me tell you a story . . .

RSS Feed

RSS Feed