And then there are those few works that stand apart, whose magnificence break through the canopy of greatness and soar to amazing heights, works that ravish me, amaze me, terrify me, thrill me to the depths of my soul. You probably have a few like that as well. For me they would be “Moby-Dick” by Herman Melville, “Absalom, Absalom!” by William Faulkner, “Gravity’s Rainbow” by Thomas Pynchon, and “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Gabriel García Márquez. The first two grew out of my high school and college years, and the latter two I encountered as a somewhat mature adult. Each one could be considered the Great American Novel, as long as we let that label embrace the Southern Hemisphere as well as the Northern.

It is no accident, I think, that all are American.

What makes these tower above the rich canopy of other favorite works of fiction I have read?

For one thing, each one shook me up in a serious manner. When I finished each one I was changed forever. Each one has its difficulties, and within each one at times you have to throw yourself in the deep in and swim the best you can to make it to the edge of the pool. Of course that will strengthen your muscles and you’ll do better on subsequent dips.

Each in its way is apocalyptic. Melville’s great white whale destroys the Pequod an all on it, save Ismael, who is left alone to tell the tale (I think of that Ancient Mariner who stoppeth one in three and trasfixes the Wedding guest with glittering eye and the tale of another ship that meets disaster). I think of Faulkner’s Sutpen whose dreams of dynasty wrenched from the wilderness is destroyed along with his family, brother killing brother leaving grieving women to watch over the mad remnant offspring. I think of that screaming across the sky that opens Pynchon’s masterwork and that ending that finds us in a theater watching a blank screen, that final white page, as that rocket plunges toward us. I think of García Márquez and that last survivor of the Buendía family alone in a room knowing that it and he will be wiped away by wind and exiled from memory “because a race condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth.”

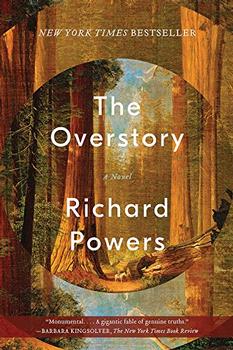

In “The Overstory” the apocalyptic catastrophe is environmental.

Suddenly it strikes me that environmental concerns suffuse those other four works as well. The whales. The primeval forests of Mississippi. The devastation of war. Jungles wiped out for bana plantations. In all of them the stealing from the world for profit for the few. That concern reaches its peak in “The Overstory.”

Perhaps a central image, certainly for me, is that of the seed of a tree that must pass through fire before it can germinate, grow, flourish. Fire. Not the water but the fire next time. And in that phrase it is neither water nor fire but the next time that resonates.

Apocalyptic, yes. But oddly with a strange bit of hope. Something small. Tiny, even.That seed that must pass through fire . . .

All of these works have large casts of characters with something hovering over and embracing: fate, doom, hubris . . . In “The Overstory” that embracing overarching unifying matter is a character itself, one that gives the work its title. We see lots of smaller stories with smaller characters and we wait in wonder as to how these tales, these people, will cohere. And cohere they do.

At the end I am left with the question as to whether I, we, can or will endure. Or even should. Dark thoughts. But all these books have their dark thoughts. If the answer is no, then what comfort there is comes from the hope that life will endure. But even there I find only hope, not certainty.

Why, you ask, does such dark material leave me with so much joy? The answer is simple. They are contained in works or art that in spite of, or in, their human imperfections sing like angels.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed