It thrills my soul.

And how can a movie whose central theme is the erosion of the human spirit mange to so inspire?

Erosion is referred to with great explicitness twice in the move. First, in a schoolroom setting mid-movie when the stern male teacher is presenting a lecture on types of erosion which his pupils are expected to write down every word. That lecture is continued in voiceover toward the end of the movie, as our young central character disappears into the darkness in the basement coal room under his home. That fade into darkness is accompanied by another voiceover, the long speech by Marita Hunt’s Miss Havisham from David Lean’s Great Expectations and a bit of Orson Welles’s’ narration from The Magnificent Ambersons. The effect is breathtaking.

He has 2 much older brothers and an older sister, and they are loving and kind. Yet, likely because they are of the courting age and the child is not, they leave him behind when it suits them to do so. There is no father in evidence, and if we have seen Davies’ earlier movie Distant Voices, Still Lives we know that the father was brutally abusive toward wife and children and is now dead.

Only his mother seems to be the solid ground supporting him. And the movie is much concerned with the great love between son and mother.

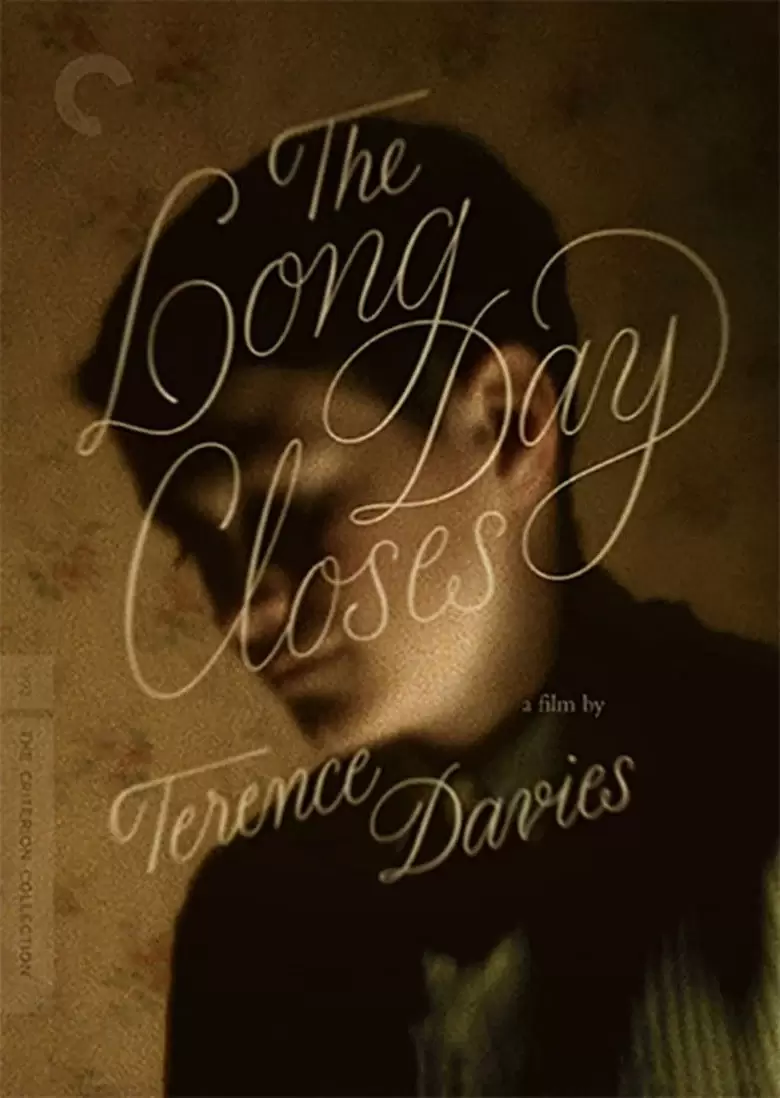

The title is that of the song by Henry Chorley and Sir Arthur Sullivan (yes, the one of Gilbert & Sullivan fame) that sung in its entirety by a male choir closes the movie. So does the movie take place in one day? One might say yes, from certain evidence, but one might also say that it take place during a year in the boy’s life. For me the work takes place in 2 overlapping timelines. Shakespeare uses a similar device in Othello, where some incidents require a long time passing and others require time compressed.

This long ending takes place after Bud disappears into the blackness in the coal cellar. It begins with Bud and a buddie sitting on the stoop of Bud’s house gazing at the sky, with Bud commenting that if you shine a flashlight up into the darkness the light will go on forever. And yet the long day closes. A conflict? Or sheer poetry. I opt for the latter.

So: young boy growing up gay with his spirit being constantly eroded in crowded conditions (the daughter sleeps with her mother) in a working class family (all 3 of the older siblings have jobs) in gray and grim post-WW2 England (Liverpool, actually), how depressing can you get?

Magically, not at all! And somewhere in that fact is why the movie is so great to me.

In part we can thank the music. The movie is filled with song. Just take a look:

The Long Day Closes (1992) - Soundtracks - IMDb

(And I have just noticed that after the Minuet under the opening credits and the Fox Fanfare the first song we hear is Stardust, and the last words in the movie refer to stars and light going on forever. Great works of art continue to open up, like flowers in spring.)

Sometimes the selections are heard as background or commentary to actions onscreen, and sometimes they are sung by the characters in the movie. I have always marveled at the use of Debbie Reynolds singing Tammy while the camera pans right to left down tenement streets, the aisle of a movie theater, the aisled of a school, the aisle of a church, and back to the tenement street. I love hearing The Carousel Waltz on the soundtrack while we see Bud in the center of the first row of a movie balcony watching that movie, and while the music continues the camera pans down into darkness and a night when Bud and his sister and his mother are walking through a fair, with the waltz gradually fading and being replaced by She Moved through the Fair, a love song to the mother. I still get gospels when we hear Blow the Wind Southerly (and bring back my lover to me) as Bud sits dreamily in a (sometimes) windswept and rain-driven classroom.

The Long Day Closes (1992) - Connections - IMDb

The first voice we hear, after Nat King Cole sings Stardust, is that of Alec Guinness (“I hear you have rooms to let”) from The Ladykillers.

It is rewarding to know the movie references, but if you do not the movie still makes perfect sense.

All of this helps lift the movie away from misery, but more important is its depiction of family love. The mother’s love for her son: perfect. A bedrock for the boy. But also, in their imperfect way, his siblings love him, and he loves them.

In spite of its depiction of the erosion of the human spirit, the movie makes grat room for resilience. The child is worn down but not defeated. The erosion wounds but does not destroy. The mere fact that Terence Davies grows up to direct many fine movies including this great one is further proof of that.

And he has made something beautiful where there might have been just misery.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed