| And a man paragliding over the sea, spots where a cliff wall has sheared away, leaving what appears to be an opening, and his subsequent exploration reveals a cave with signs of habitation, human and otherwise, going back millennia. Scientists begin excavating and eventually the media and the public are enthralled. I don’t consider any of that spoiler. A comparison: if I told you that “Psycho” begins with Janet Leigh stealing cash from her boss and fleeing in her car, having second thoughts, and checking into a motel during a rainstorm, I wouldn’t consider that a spoiler either. Just setting the stage. |

We know as much as each character, but we know more than any single one for we have picked up other bits from other characters. Little happens in the first third of the novel after the camper incident, but suspense and tension are built as we learn more and start building a scenario in our minds. When a reporter listens to a fairly dry scientific lecture on discoveries in the caves we find ourselves cringing even more than she does. What, we worry, is going to happen to her and with others whom we have met and in whom we have become invested? Just as we begin to worry when Janet Leigh checks into that motel.

We know there are some bad people about, for we recall those campers. But is there something else? Something evil, something persisting from eons past, something even supernatural.

Here let me insert a quote from the intriguing afterword Nevill has appended to his novel:

After describing the Devon are where he lives and which he features prominently and beautifully in this work, he writes: “I lacked a specific image that might lend itself to horror – though time itself, and a sudden revelation of one’s insignificance within a vast landscape, or before an enormous body of water, can be pure horror of the most sublime type, that involves equal parts terror and wonder. But, for a novel-length story, I needed something localised, specific, more tangible, a kind of metaphor for time, our origins and those incomprehensible stretches of time existing before we stood upright and systematically rid the planet of its mega fauna and flora.”

Then he describes how that specific image came to him. But in the novel itself that image is not quite described but comes to us more through hint and suggestion, and the image that we create in our own minds surpasses what even Nevill with his own substantive writerly talents might be able to specify.

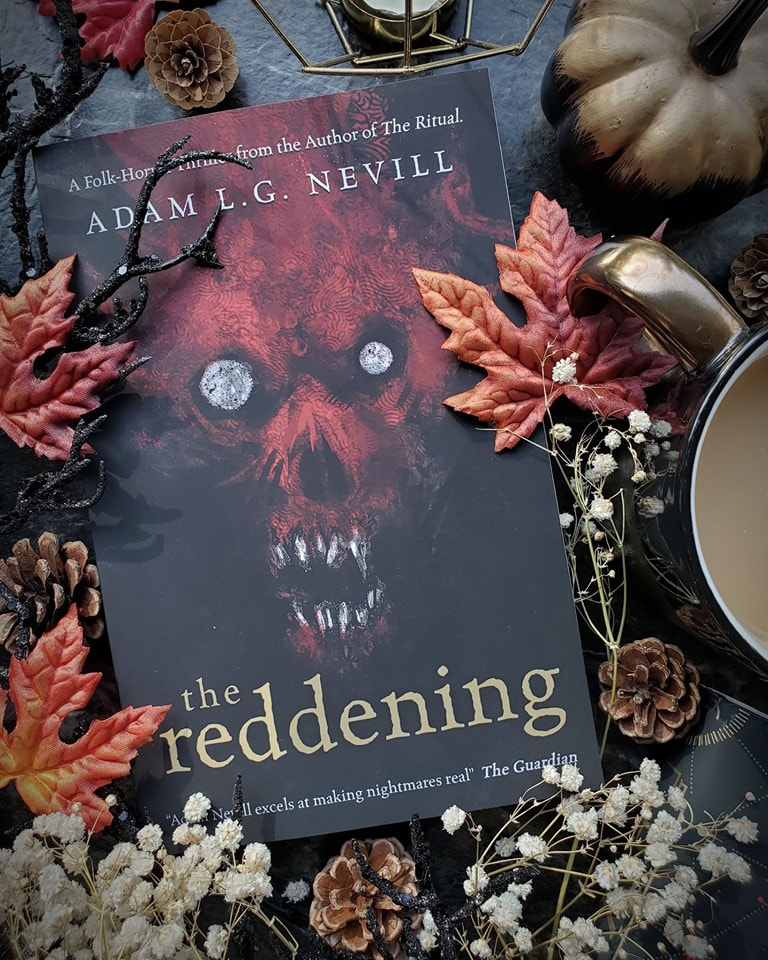

You’ve seen the cover. Is that what it looks like? I can’t answer that, although I’d suggest it is an image suggested to the illustrator by the author’s prose and his own imagination. One might view that cover as an illustration of not so much what lies beneath the ground as what lies beneath the face of mankind.

In my lengthy quote from the afterword Nevill talks about our insignificance before a vast landscape or enormous body of water. You feel that in this novel, but you also get a sense of the beauty of both and of his own vast love for both. Elsewhere he has written about The City as a place of horror and terror, and here he finds it in the beautiful rural setting as well. I don’t think he would object if I suggested that there is something common to both city and country: us.

In a way, that quotation above could have been written by John Langan after his novel “The Fisherman.” Both novels share a strong sense of place as well as a sense of the vastness in which that place lies, Nevill’s in Devon, Langan’s in the Adirondacks. In both the micro and the macro interweaving. That sense of insignificance before the vastness of time and space are what link both Nevill and Langan to H. P. Lovecraft. I find that also in an unexpected place: Terrence Malick’s movie “The Tree of Life,” unexpected because that is not generally thought of along with horror novels. That movie, which views a boy growing up in small Texas town in the 1950s against the backdrop of the birth and death of the universe, ends not in horror but in something I might call resignation and acceptance. Nevill’s book shows us an ending, sort of, for each of his two central characters. But even at the end we the reader know certain things that the characters do not. One ending suggests something like the mood at the end of that movie. The other suggests something more closely reflected by the cover of the book. I believe Nevill fears the one but still has hope for the other.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed