| The Nichols movie was released in 1966. At the time I loved it but preferred the play onstage. The stage set was a standard-issue living room with doors to the outside and to other rooms with a big couch in the center. There have been thousands of plays with that basic set. Superficially it seemed to be realistic. But simply because it was on a stage and revealed by a curtain that rose up it had an artifice that worked particularly well for the more extravagant turns of the plot. That aspect of the play still does not work for me quiet as well in the movie. Also, the claustrophobia induces by the 4 characters screaming at each other as if in a hell they cannot escape is stronger onstage: the slight opening up in the movie dilutes that just a bit. |

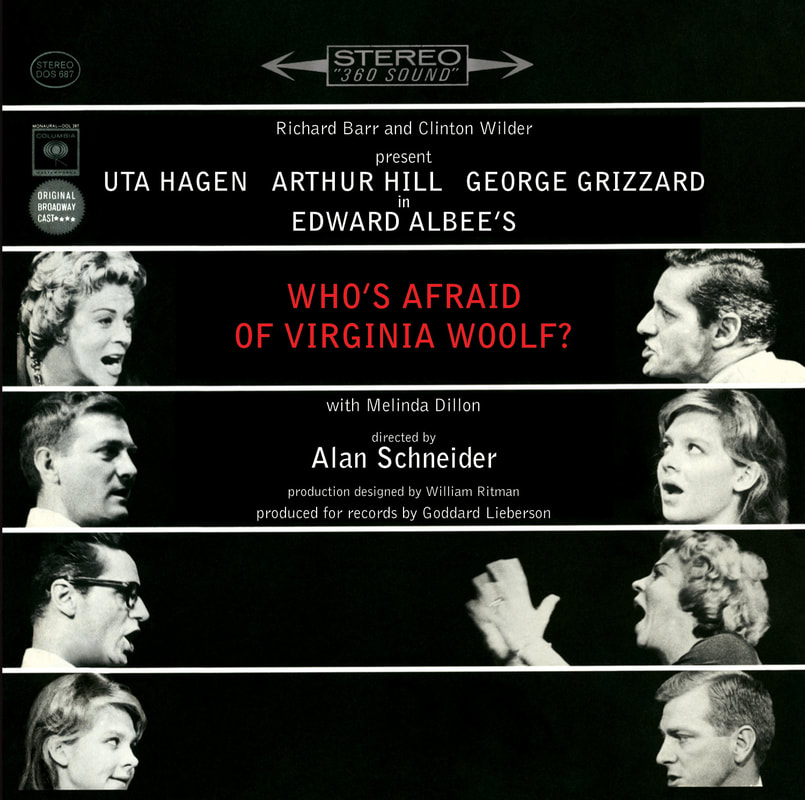

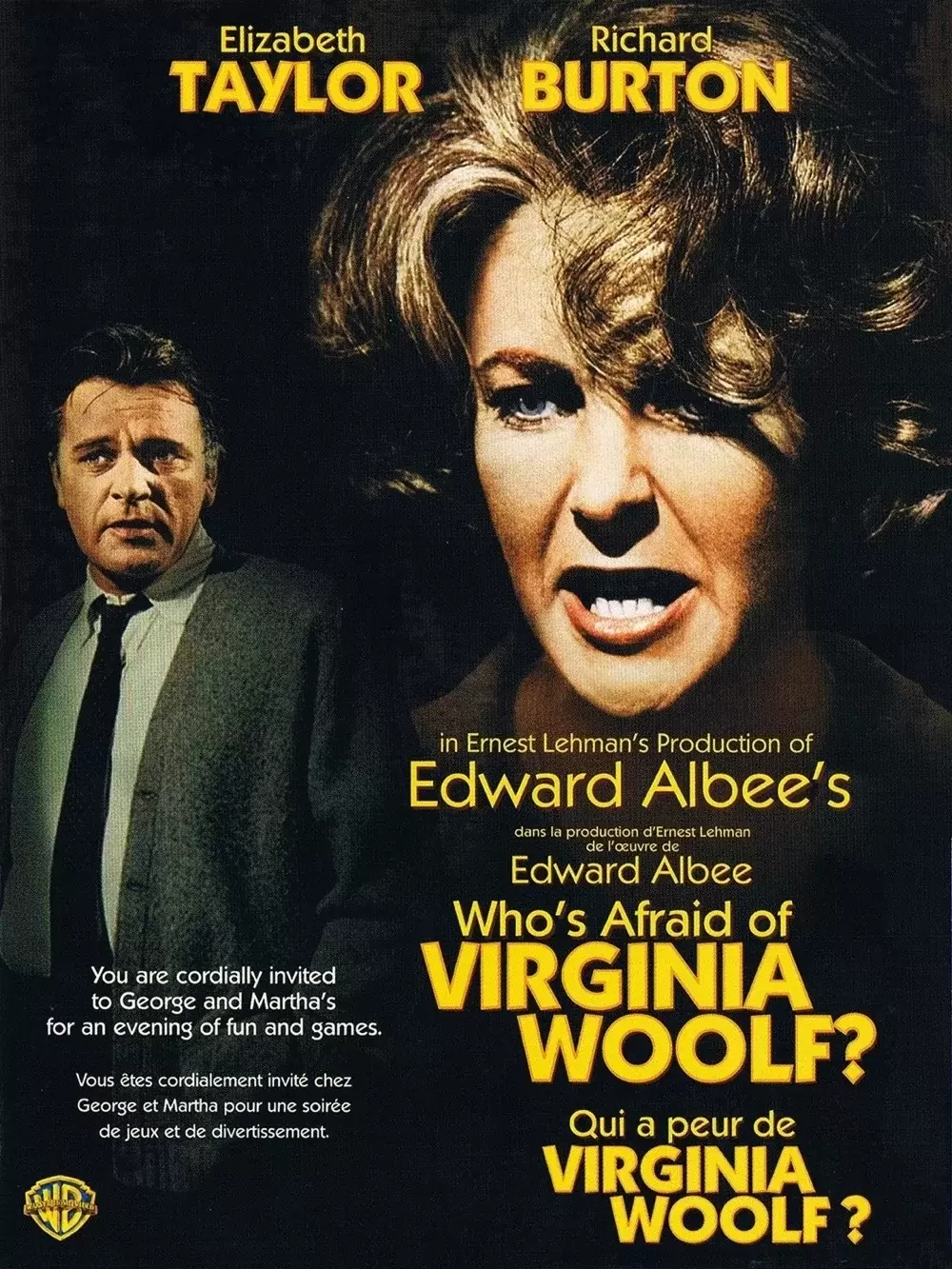

(Close runner-up: Sidney Lumet’s “Long Day’s Journey into Night.”) Both Elizabeth Taylor and Sandy Dennis won Oscars for their performances. Both deserved. I think neither were as fine as Uta Hagen and Melinda Dillon (Remember her? The mother from “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”) onstage. Taylor is especially fine, but in spite of attempts to make her blowsy and homely somehow a bit too much of her incredible beauty and glamor shines through.

Both Richard Burton and George Segal were nominated for Oscars, but both lost. Burton, I think, gives the finest performance in the movie and one of the finest of his career. It is a shame that he lost.

But still, one of the finest movie adaptations ever of a play.

Many years later Nichols did another fine job with a play in his 6-part “Angels in America” for HBO.

In 1964 I was fortunate to get to see Paul Scofield in “King Lear,” designed at directed by the great Peter Brooks, at the New York State Theater. There was only one break, coming immediately after the horrific blinding of Gloucester. I fled out onto the balcony for air, and there was Elizabeth Taylor, luscious and lovely surrounded by a bevy of gorgeous young men dressed to the teeth, Taylor being the prize rose at the center of the bouquet. (Taylor always did love her gay buddies.) The shock of this vision coming directly after the horror just seen overwhelmed.

Taylor was in town with Richard Burton, then starring further downtown in what I still believe to be the finest version of “Hamlet” I have ever seen. It was directed by John Gielgud, who also provided the voice of the ghost of Hamlet’s father. Burton’s performance (as well as the production) did not get particularly glowing reviews, which I believe was the intellectual fraternity’s trying to punish Burton for his being in “Cleopatra.” I had no reservations and loved it.

Those were interesting times for me theatrically. But to wander back onto what is more or less topic: the movie.

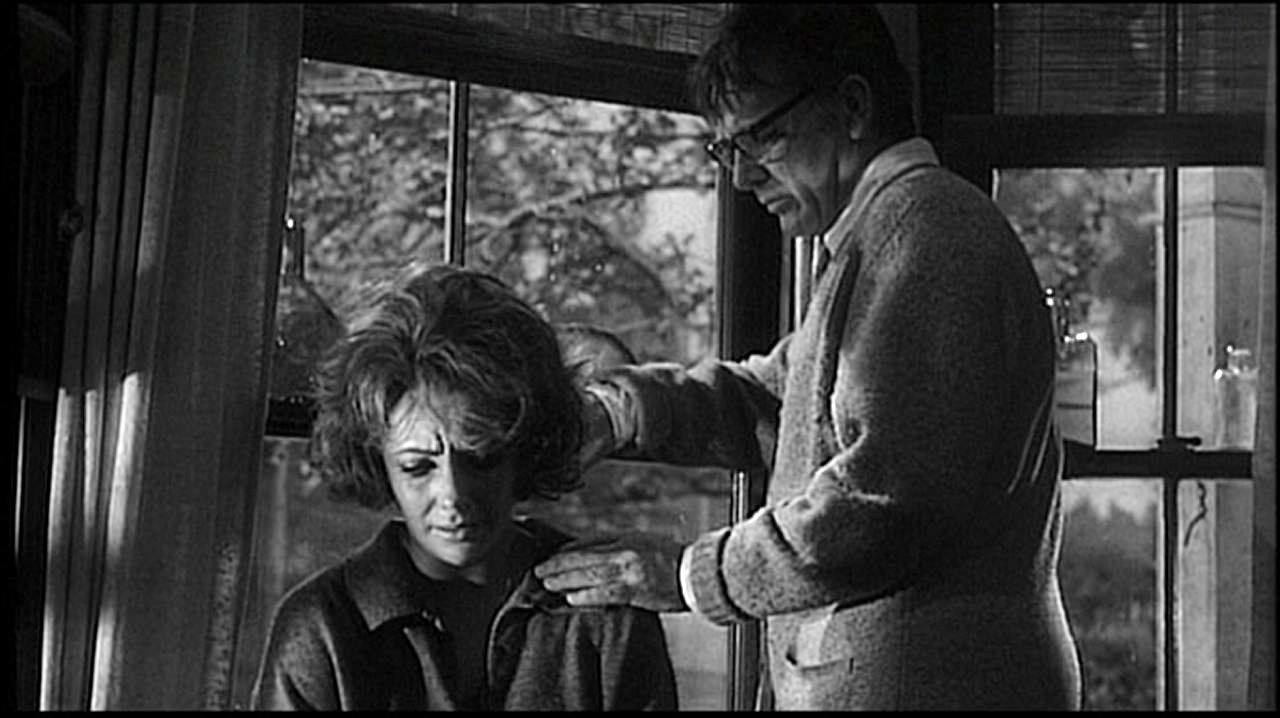

As much as I feel that opening up harmed the work a bit, I did approve of moving the long George/Nick scene outside. Something about that rope swing seems particularly inspired thematically. A child could swing on that . . . And the texture of the oak trunk is absolutely great behind Burto’s face. Especially in the most extreme closeups.

I’m delighted to have seen it again.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed